Look closely at the bricks that cover Embarcadero Plaza. Some, along the stairs on the west side, clustered in cumulous groups beside newer bricks, are notched with a scattering of small, dark pockmarks.

Any skateboarder would recognize these as axle marks made by the horizontal alloy bar that holds your wheels to your trucks. When the board doesn’t fully flip under a skater’s feet, the deck can land in a position that we skateboarders call “Primo,” after the famed freestyle skater Primo Desiderio (opens in new tab), who, alongside his wife, Diane, spent a lot of time dancing on the vertical edge of freestyle boards in their popular synchronized performances in the late ’80s.

No disrespect to Primo or Diane, but by the time the bricks at Embarcadero started to get hammered by skateboard axles — roughly between 1989 and 1993 — the crowd-pleasing choreography of freestyle skaters was considered “cut,” phased-out by street skating.

With street skating’s growing popularity, tricks featuring flips became more common, as did falling while trying kickflips. To land “primo” is to stop dead, to miss the trick, to slam. This happens more often than not while skateboarding, and more often than not, skaters doggedly try the trick until they land it. (opens in new tab)

Those tiny indentations on the windswept Plaza in front of the Ferry Building testify to countless tricks tried and missed — to the toil of imperfection that we all go through to reach those fleeting moments of perfect equipoise: when the trick you’ve been trying for hours — sometimes days, if not weeks — actually works.

Feet land back on your board, grip-tape side up and four wheels back down on the ground, mind clear and every nightmare scenario of previous tries expunged. These marks tell that story of dogged struggle and fleeting triumph, legible to any skateboarder.

Tantamount to a “Hey, skate here!” sign, those marks on Embarcadero Plaza represent a skater’s walk of fame, if you know your history.

Mike Carroll and Jovontae Turner

Lavar McBride

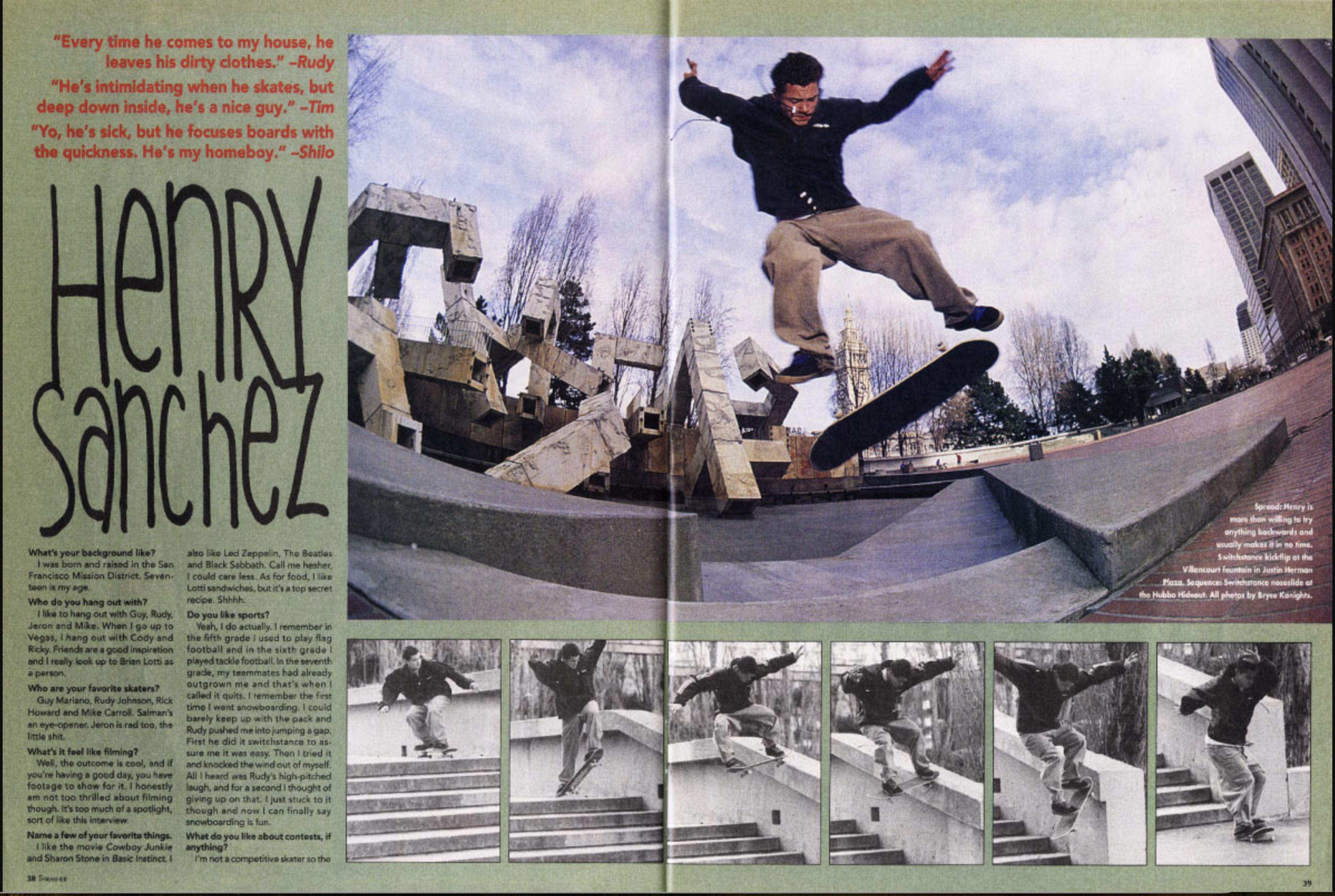

Henry Sanchez

Karl Watson

James Kelch

Moving from the skatepark bowls and backyard ramps of its past, skateboarding found its most iconic expression against the backdrop of San Francisco’s skyline. Footage (opens in new tab) and photos (opens in new tab) from this time show skateboarding to be at the center of a cosmopolitan city: the coolest, most stylish, most challenging and most advanced thing anyone could do (opens in new tab).

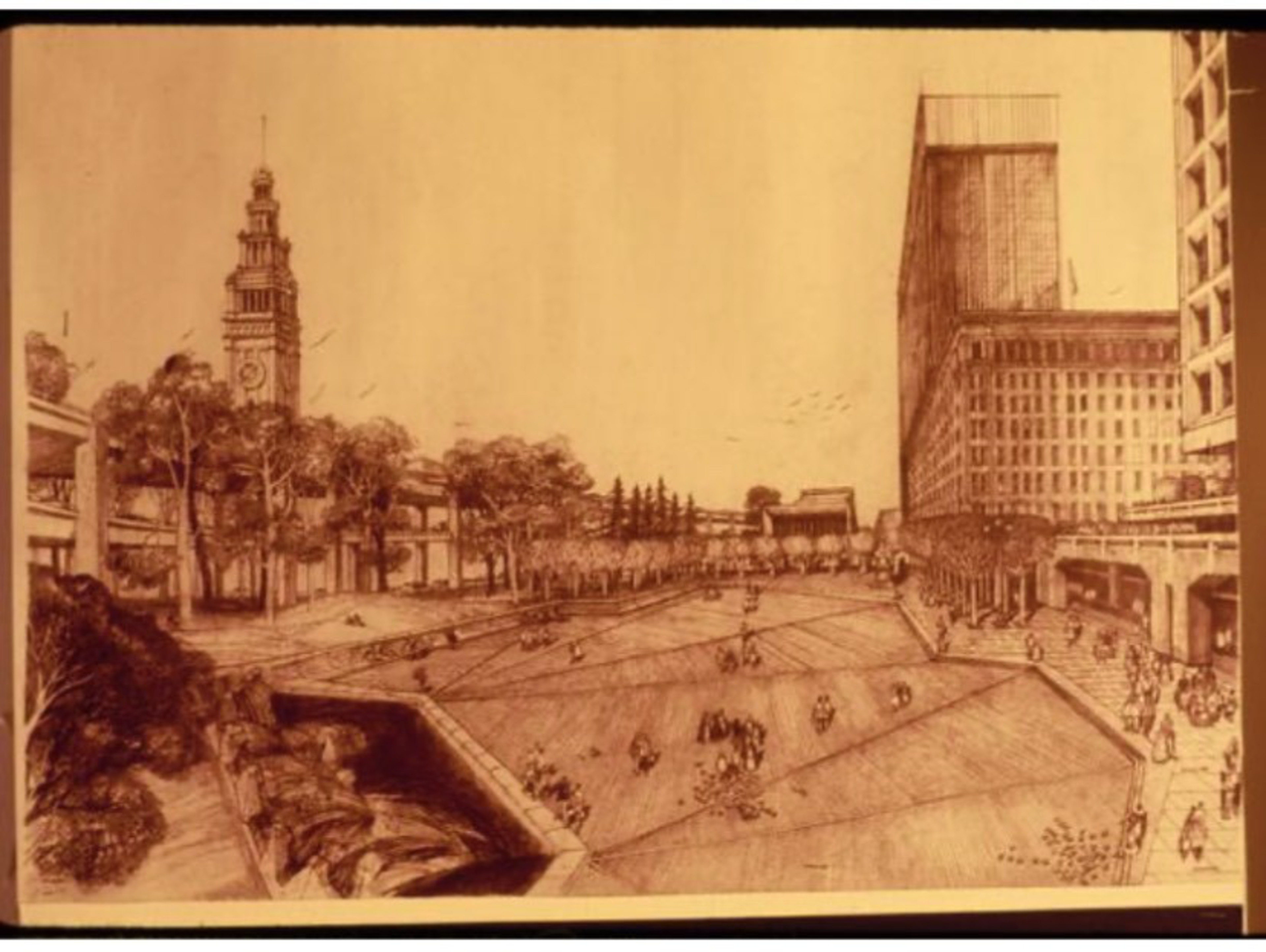

But most of the marks seen on the bricks at Embarcadero denote tricks attempted on a concrete ledge that is no longer there. The plaza has undergone many iterations since the early 1970s, when it was executed from plans by Mario Ciampi, John Bolles (who invited Armand Vaillancourt to design the eponymous fountain on the northwest end of the plaza), Don Carter and Lawrence Halprin.

Originally conceived as a late-modern take on Siena’s Piazza del Campo, with its own angled nine brick slabs radiating from the corners of Vaillancourt’s fountain, the plaza gained steps and ledges in 1982, lost them at the turn of the millennium and gained new ledges, steps and planters that briefly rekindled interest in the spot before familiar (and expensive) skate-stopping brackets were added.

Recently, prompted by optimistic AI-generated renderings of a transformed waterfront at the terminus of Market Street, a new debate has emerged. Developers, designers, mayoral candidates and critics cite other conspicuous projects like Manhattan’s High Line and Chicago’s Millennium Park as models to emulate here — as if the miles of green space, bike paths, pedestrian areas and other waterfront redevelopments over the past two decades along the Embarcadero south of Market Street had not already been built and seen negligible success.

It seems unlikely that, fountain or not, the character of the Embarcadero will ever be similar to that of Tunnel Tops in the Presidio, the gold standard of modern SF greenways. Different settings demand different solutions. Perhaps part of Tunnel Tops’ appeal is its setting within the Presidio, its parking access and the views of the Golden Gate Bridge (none of which can be claimed by the Embarcadero).

Two years ago, $1.5 million was spent to erect a temporary “San FranDISCO” roller-skating rink (opens in new tab)at Fulton Plaza. Tickets ranged from $5 to $15 (in one of the most impoverished parts of the city), and, after the initial burst of interest from San Francisco’s roller-skating community, attendance dropped with a thud. Maybe it was the wind, or perhaps the adjacent open-air drug market, or maybe it was simply that roller skaters preferred to skate in beautiful Golden Gate Park or indoors and warm at the Church of 8 Wheels. An idea that works in one place seldom works in another in this city of intense microclimates.

Nearly all of the voices within this debate about the fountain’s fate assume that the brick plaza that surrounds it will go. If this happens, that irregular palimpsest surface of pockmarked bricks, which constitutes what for many skateboarders is the spiritual and historic heart of our culture, will be erased without a trace. Outside of San Francisco’s ups and downs, oblivious to the city’s shifting national profile and reputation, skateboarders have been coming to skate here for decades. That legacy, like so many others in this history-addled city, should be preserved.

At the end of the last millennium, as the Embarcadero was redesigned in the midst of the first tech boom and bust, skateboarders returned here to skate. Despite being criminalized and aggressively policed for three decades, we gathered at the foot of Market Street. Lately, we come to pay homage to historic sites, sometimes simply to look at old skate spots or to feel the sound of rolling on those puckered bricks.

There isn’t much else to do at the Embarcadero if you’re a skater; so much has been taken away. But first-year skaters and veterans alike understand the inexorable draw this place has: a monument to a time when San Francisco was the magnetic center (opens in new tab) of skateboarding’s universe (opens in new tab).

For us, it doesn’t matter that Halprin’s ideas of medieval Italian urbanism didn’t work for everyone else — that plaza worked for us. Once our Colosseum, Embarcadero is still a pilgrimage site whose poignant beauty rests in a reverie of what once was. To preserve it is to recognize that living in a city means learning to adapt to and find joy in what you cannot change. Those marks on those bricks tell that story.

You could learn a lot from the skateboarders who learned to love San Francisco for what it is.

Ted Barrow is a skater, art historian, lecturer, curator and host of Thrasher Magazine’s YouTube series “This Old Ledge (opens in new tab).”