When Daniel Lurie issued one of his earliest policy directives, a February order (opens in new tab) intended to reform the city’s sclerotic permitting system, I called the move a “sly consolidation of power,” one that demonstrated the neophyte mayor’s surprising political chops.

At the same time, I noted that details were lacking about how the creation of an interdepartmental PermitSF initiative would streamline a system synonymous with corruption, complexity, and soul-crushing wait times.

Six months on, the mayor’s team is doing more than talking. Lurie’s economic development team has decided against expanding a software system used by portions of the city’s bureaucracy in favor of a newly chosen platform that aims to integrate the permitting processes for city departments. The fact that the maker of the software, a 13-year-old company called OpenGov, has an eyebrow-raising connection to someone in Lurie’s inner circle and wasn’t previously on the list of approved San Francisco vendors may spark some controversy. Nevertheless, it shows the promise of Lurie’s try-new-things approach.

In fact, everything about the process speaks to the mayor’s campaign promise of bringing in fresh ideas and people — notably from the private sector. If this tech implementation sticks — and that’s a big if — it will be a triumph of business-world savvy over bureaucratic dithering. And it will result in the improvement of one of the things that drives San Franciscans berserk: the inability of their government to get shit done in a timely fashion.

Lurie was smart to zero in on permitting, which involves everything from simplifying how restaurants can add sidewalk seating (a (opens in new tab)recent, relatively easy fix (opens in new tab)) to one-stop applications for multiple licenses, the goal of the new software. It was also something of a banana peel for his predecessors, who made several failed runs at the problem, often on a department-by-department basis.

A recent example: The Department of Public Works agreed in 2021 to implement an online permitting program from a company called Clariti, a process it began the following year. By 2024, having failed to make progress, DPW did a reset and (opens in new tab)agreed to spend $2.7 million (opens in new tab) on a system that would be ready by this January. That didn’t happen either. A limited version of the Clariti system should be up and running in January. Maybe.

Lurie’s team decided to go bigger. It issued a (opens in new tab)request for information (opens in new tab) in May that asked all vendors, not just those that already had been approved, to pitch the city on a system that would work across departments. A telling nugget from the information request is an appendix that lists 20 different software platforms the city currently uses. The plan was to preserve four — a state licensing system, the 311 call center, an identity-management system, and a financial management package — and eventually rip out everything else. (The new software initially would integrate with Clariti, whose future would then be uncertain.)

This quest to go beyond the established list — what the city calls its technology marketplace (opens in new tab) — is key to understanding the new approach. What the city terms an “efficient purchasing model” dates to the 1990s and limits the field of bidders. By simply asking for “information” on how a technology company would approach the city’s problem, Lurie’s team was able to surface new potential partners. It’s easy to see how such a tactic would excite newcomers and annoy old-timers.

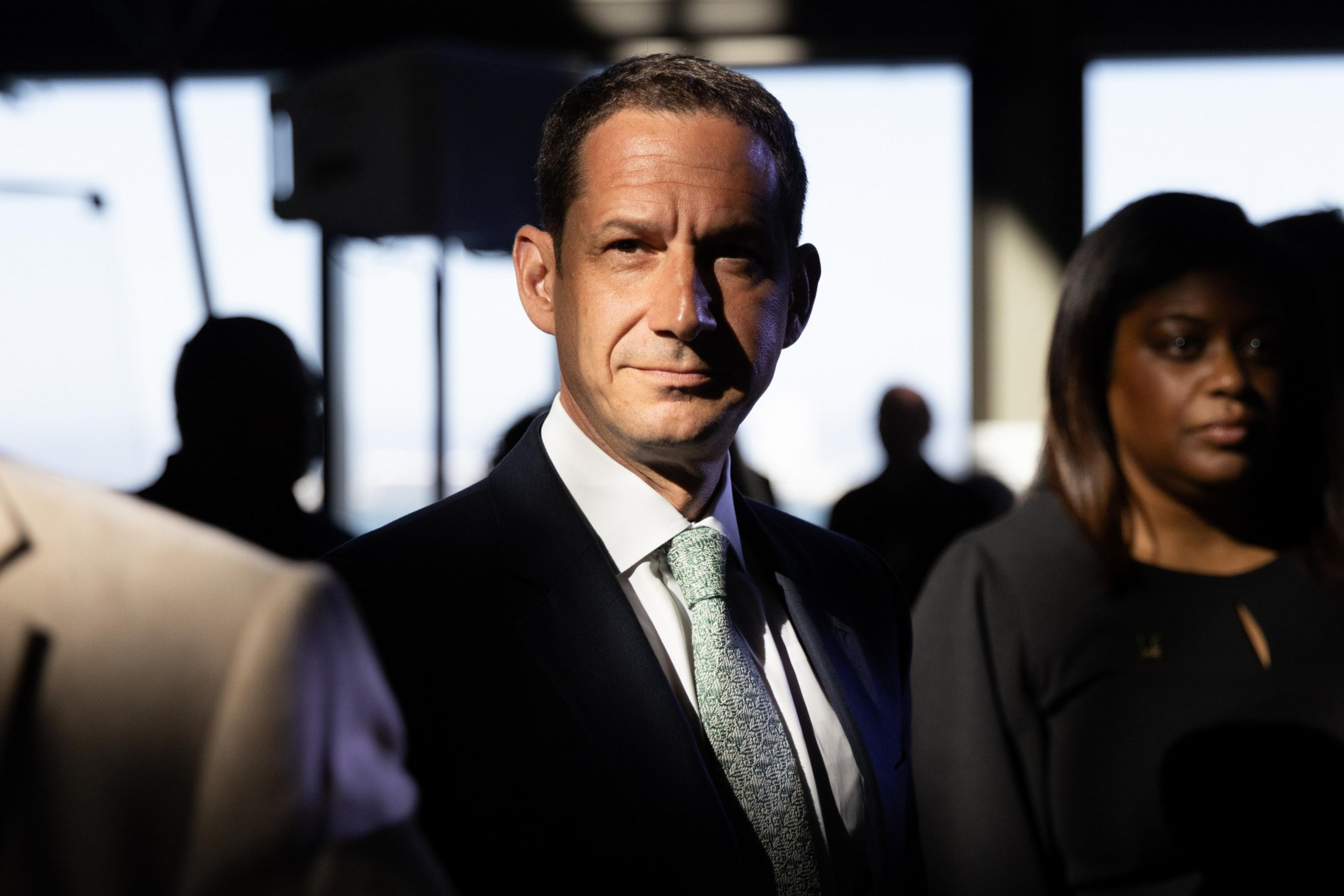

Florence Simon, director of the Mayor’s Office of Innovation, told me 50 companies responded to the request. Of those, 15 were selected to present at a two-day “showcase” in July attended by more than 50 officials from DPW, the Department of Planning, the Fire Department, the Department of Building Inspection, the Department of Public Health, the Public Utilities Commission, and other city agencies. Six of those companies made it to the next level, and on Aug. 14, Ned Segal, Lurie’s economic development chief, informed the PermitSF leadership team that OpenGov was the winner.

The way this decision went down illuminates how power is wielded in Lurie’s City Hall. Segal and Elizabeth Watty, director of current planning for the Planning Department and leader of the PermitSF initiative, made the decision alone. They took input from the various officials who vetted the vendors, but theirs were the only votes.

Though Watty is a 20-year veteran of city government, Simon and Segal are typical of the types of people Lurie has brought into City Hall to shake things up. Simon is a former McKinsey consultant and staffer for former Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, who took up the innovation role in March. Funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, the position has become a springboard: Supervisor Stephen Sherrill and Budget Director Sophia Kittler previously filled it.

I asked Simon why OpenGov won out. She said it was a combination of an assessment of the company’s team, its track record for integration and support, testimonials from existing customers, and future product plans. “They are a smaller, more agile player with a limber roadmap,” she said.

As for Segal, a former Goldman Sachs banker and, more recently, chief financial officer of Twitter, he simultaneously has become Lurie’s emissary to the business community and chief proponent of bringing a commercial mindset into City Hall. He told me that trying to implement a single software program for many departments is a risky proposition. The process is new, the stakes high, and the timeline tight: The mayor set a February deadline for implementing the system.

“My dream is that this goes well enough that others will want to come work in city government and that people in city government will want to do things differently, with the goal of delivering better outcomes together,” he said.

I have already heard of grumbling within city ranks about the prospect of ripping out old systems and trying something unproven. There is particular resistance around replacing Clariti, given the years DPW has invested in it. The grumblers could be an impediment if they drag their feet, something of a core competency in San Francisco government. Segal might have been anticipating this in his email to PermitSF’s leadership team about OpenGov’s selection, calling for “collaboration and alignment” to meet the “bold timeline for first launch.”

It also may court controversy that OpenGov — which was founded in San Francisco but sold a controlling stake of itself last year to cable giant Cox Enterprises for $1.8 billion (opens in new tab) — has ties to Katherine August-deWilde, a former president of First Republic Bank who is president and CEO of Partnership for San Francisco (opens in new tab), a Lurie-allied group comprised of CEO-level executives. August-deWilde was a board member of OpenGov before its sale to Cox, and along with former Cisco Systems CEO John Chambers and venture capitalist Joe Lonsdale, she remains an advisor (opens in new tab)to the company.

August-deWilde told me by email that she no longer is an OpenGov shareholder and that she had no involvement with its selection as a city vendor. As for the advisory role, she said: “I understand that to be something of an honorific title. The advisors receive no compensation, and there have been no meetings.”

Oddly, the city isn’t yet saying what the OpenGov software will cost. While PermitSF has selected the company as its preferred vendor, it has not begun the official procurement process. Suburban San Rafael uses an OpenGov permit-management system at a cost of $112,000 a year. San Rafael is less than a tenth the size of San Francisco.

Knowledgeable people I spoke to outside of Lurie’s PermitSF team tell me that if the mayor’s minions can pull off the OpenGov implementation, it genuinely will represent something that hasn’t been done before in San Francisco. It is a sad fact that the city’s government agencies are a technological backwater, a notable embarrassment given they're located in the global capital of tech. Look no further than BART only now introducing world-standard tap-to-pay technology, with Muni and Caltrain still behind the curve.

Much has been written about the vibe shift in San Francisco, and about the appearance of progress whether or not conditions actually have improved. Something as mundane as well-functioning technology that reduces aggravation would constitute both the perception and the reality of progress. Let’s hope this thing really works.