Ensnared in a bribery scandal over raising the rates San Franciscans pay for garbage, trash-hauling giant Recology is now trying to rein in the city’s attempts to reform the very process its executives sought to abuse.

The company enjoys a highly unusual monopoly on garbage collection in San Francisco that has long been enshrined in local law and can be changed only by ballot initiative. City officials want to be able to alter the way garbage rates are set without going to voters, who have been readily persuaded by expensive Recology election campaigns in the past.

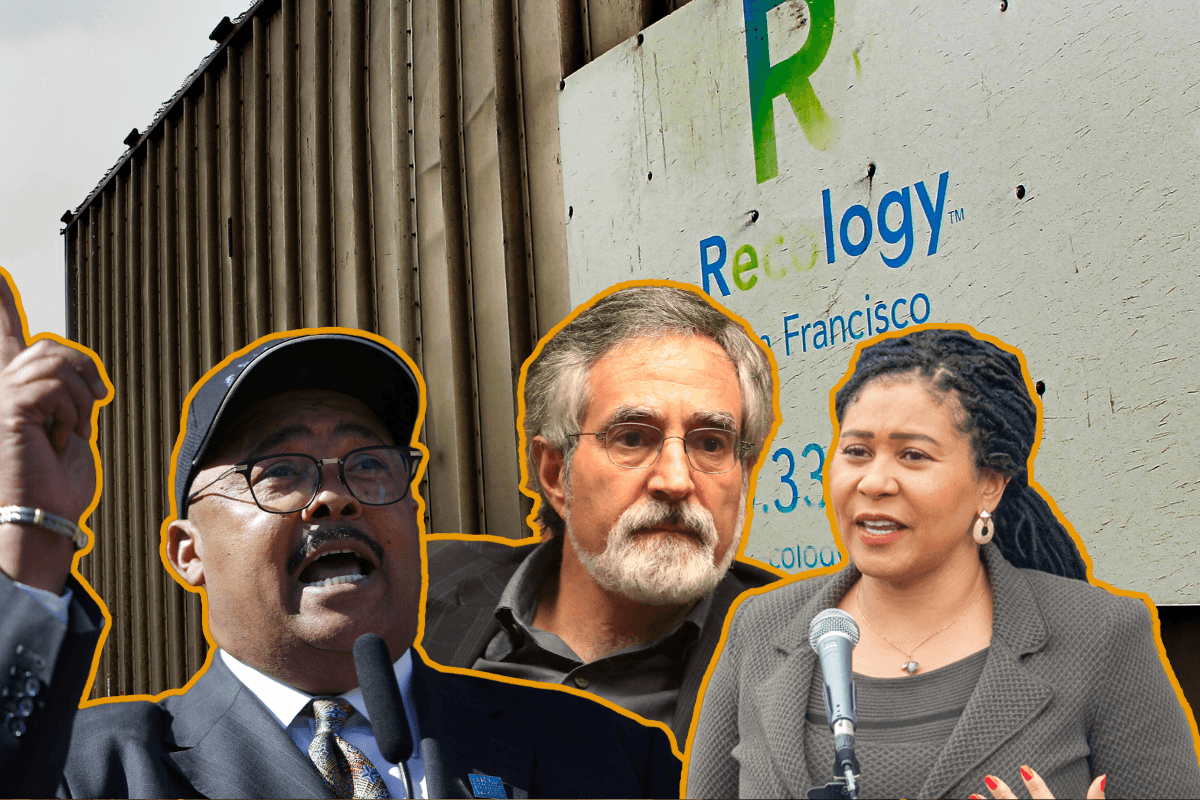

Both Recology and the city are now working on tight deadlines to get proposed reforms to the rate-setting process for trash collection on the June ballot. After being sent a draft of the ballot measure that Supervisor Aaron Peskin and Mayor London Breed are considering putting forward, Recology essentially rewrote the proposal and submitted its own watered-down version to elections officials to begin gathering signatures.

“The city has yet to actually formally introduce its measure,” Peskin said. “Sadly Recology walked away from the table and has decided to go the political route and dump millions of dollars of the ratepayers money into this.”

Last September, three Recology subsidiaries admitted in federal court to conspiring to bribe former San Francisco Public Works head Mohammed Nuru in exchange for his help raising garbage rates. A separate investigation by the city found that the firm also overcharged San Franciscans nearly $95 million through its cozy relationship with Nuru.

The ballot measure being considered by Peskin and Breed would enable City Hall to make changes to the rate-making process, with the goal of giving the city more flexibility to fix issues and regulate Recology more closely should the firm run astray again.

“What the city proposed was a strategy where if they didn’t play by the rules, that the city could come down on them,” said Peskin, who co-chaired a Controller’s Office working group to assess potential rate-setting reforms alongside an advisor to Breed. “What they are proposing to the voters takes that out.”

A Recology spokesperson, Robert Reed, said the firm supports “stronger controls, greater transparency and stricter accountability,” but was surprised by the recommendation to “completely remove voters’ authority over the rate-setting process and transfer voters’ power to City Hall instead.”

In records filed with the Department of Elections, Reed wrote that the purpose of the Recology initiative was to “make necessary reforms to the rate process while at the same time ensuring that the voters, not politicians, have the final authority over how the charges we pay for recycling, composting and garbage collection are set.”

Recology and its predecessor firms have enjoyed a monopoly on waste collection in San Francisco for decades under a voter-approved ordinance from 1932.

The ordinance divided San Francisco into 97 garbage routes and allowed only licensed providers to work them. While the city initially issued permits to various companies, Recology’s predecessor firms secured all of them over time.

The ordinance also outlined a rate-setting process that still exists 90 years later.

Currently, Recology submits an application to the director of San Francisco Public Works whenever it wants to raise rates. The director then holds public hearings and puts forward their own recommended rate increases. Those proposed rates are then adopted unless successfully appealed to the Rate Board, a body that includes the city administrator, controller and Public Utilities Commission general manager.

Both proposed ballot measures would reform that system by replacing the director of Public Works with the controller as the most powerful player in the process. The controller’s position on the Rate Board would then be filled by a ratepayer advocate.

The proposals would also require regular monitoring of garbage rates to ensure that errors like the one that led to residents being overcharged $95 million for garbage collection do not go unchecked in the future.

The measure Breed and Peskin are considering would permit further changes to the process without a vote—and Recology’s proposal is designed to beat that back.

Another issue surfaced by the proposals is the regulation of commercial rates.

In elections records, Reed wrote that the Recology proposal would “expand the responsibility of the Rate Board to oversee rates not only for homes and apartments, as under current law, but also for commercial customers, including apartment buildings.”

However, Peskin questioned the extent to which the Recology proposal would allow the Rate Board to regulate commercial rates and said he wanted the city proposal to directly authorize such regulation. Currently, the 1932 ordinance only covers the process for setting residential rates.

“We have evidence that the commercial rate payers are overpaying and subsidizing Recology,” Peskin said. “We want our mom and pop businesses to pay fair rates.”

Neither proposal would break up the Recology monopoly.

After the Nuru scandal broke, Peskin convened a Controller’s Office working group to weigh different options for restructuring local garbage collection. The group considered putting a city garbage contract out to bid or creating a municipally run garbage entity as alternatives to the current system, but settled on proposing reforms instead.

Informed of the Recology proposal, retired Judge Quentin Kopp blasted the initiative as a distraction meant to undercut critics. He has long called for the city to open up the garbage business to competitive bidding.

“Even though the controller is virtually the only honest trustworthy public official in city government, it’s a Recology trick to fool ratepayers by not implementing competitive bidding for garbage collection,” Kopp said.

Recology has until Feb. 7 to collect and submit 8,979 signatures to qualify for the June ballot, while Peskin has until March 4 to push his proposal through the Board of Supervisors.

Peskin called the counter proposal a return to “bad old ways” for Recology.

“The city put forward a very reasonable, rational plan and Recology took the matter into their own hands,” he said. “They think they can buy the voters of San Francisco.”

michael@sfstandard.com