For Kathy Broussard, working as a San Francisco government employee for 18 years has meant keeping her head down in the face of an onslaught.

“I was harassed. I was called the N-word by my manager and director,” said Broussard, a 54-year-old Black transit worker.

So in 2010 she filed a lawsuit alleging that she’d been passed over for promotion due to her race and that her manager had made unwanted sexual advances. Ultimately, she settled with the city—but not until more than a decade later in 2021.

By reputation, diverse and liberal San Francisco presents itself as the kind of city where stories of discrimination like Broussard’s should not unfold. The city has undertaken at least a half-dozen major anti-racism reform projects since the 1970s, each aimed at turning the page on inequality.

The city set up a racial equity department a year before the George Floyd protests in 2020 sparked similar efforts throughout the country.

“Equity has to be at the forefront of what we do,” Mayor London Breed said in a 2021 forum at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. “Since I’ve been mayor, I’ve made it clear to all department heads.”

San Francisco is now entering what is supposed to be a crucial phase in a citywide effort meant to end the kind of discrimination—inside of city government and outside of it—that Broussard said she faced.

Yet today, nonwhite San Franciscans remain the poorest, most incarcerated and least housed people in the city and are paid on average less than their white counterparts inside City Hall, according to a report from the city Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office (opens in new tab). And Broussard is skeptical of the city’s efforts to rectify this.

“All these racial equity action plans are just that: plans,” she said. “No one is following through.”

San Francisco created its Office of Racial Equity (opens in new tab) in 2019 hoping it would lead a charge to end racism at City Hall. It would provide racial fairness plans for each city department. It would measure how agency budgets hurt or help nonwhite people. And the office would provide the city with analysis of new laws based on whether they affected racial equality.

But there’s scant evidence of genuine progress toward those goals. The agency meant to rid the city of racism wields little power. It’s lacked a director since 2021. And it has just two staffers to grade equity plans for 52 city agencies.

Most departments fulfilled the requirement of creating some sort of strategy. But they have barely taken the additional steps demanded by the mayor’s equity policies, according to explanations accompanying the plans.

Breed’s office did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

Broussard’s experiences over the past several years further underscore the lack of meaningful progress. And she is not alone in questioning San Francisco’s commitment to racial equality.

The problem of racism remains entrenched in the very operation of the city, said Anthony Travis, a former laborer for the city’s Public Utilities Commission who has a pending racial discrimination legal claim against the city.

“You won’t find many Blacks Downtown giving people orders,” he said. “No power or structure for minorities: I think that’s the problem.”

In keeping with the 2019 mandate, each city department assembled a team to lead racial equity efforts and also surveyed staff about their opinions around race. These agencies also developed plans to diversify hiring, build a work culture focused on equal access to opportunities, and be more fair about meting out discipline, offering training and giving promotions.

The next phase of this effort rolls out this year, with the idea of improving matters beyond just city workplaces and also rooting out racism in companies that do business with the city.

It’s a noble idea. And city leaders acknowledge that it will take more than just a new mini-agency dedicated to that task.

“The goal is not to just have an office to say we have an office,” Breed said at the MIT event. “There’s been a lot of uncomfortable conversations in the process to create a road map to change.”

Staffers in some city departments are encouraged. The city Department of Elections has gone the farthest of all city agencies working to meet city equity goals. It has revamped rules on hiring, promotion, discipline and worker retention.

A mayoral aide referred questions about the city’s progress on these issues to Sheryl Davis, who heads the Human Rights Commission, the agency overseeing citywide efforts.

“I think it’s a challenge for any city that’s trying to undertake this,” Davis acknowledged.

It’s possibly too much of a challenge, says Dante King, who is part of the Black Employees Alliance and recently settled (opens in new tab) with the city over his own lawsuit alleging discrimination and retaliation.

“The Office of Racial Equity has no teeth,” said King, who led racial fairness efforts at the city’s Department of Public Health (opens in new tab) and Municipal Transportation Agency. “It’s an empty pipe dream. It has produced no change.”

Since the Office of Racial Equity’s founding, the share of city managers who are African American has increased by less than 1.5%.

The equity agency is supposed to have five employees. It has so far hired only three. And it’s gone without a director since the July 2021 departure of its first chief, Shakirah Simley (opens in new tab).

A hearing on the Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office report that was postponed last summer has yet to be rescheduled. Meanwhile, employees feel they haven’t been given time to perform equity project tasks and don’t have clear department goals for complying with the mayor’s mandate, according to Office of Racial Equity emails obtained by The Standard.

Perhaps greatest among the obstacles is a difference of opinion—divided along racial lines—about whether the city really does have a racial equity problem.

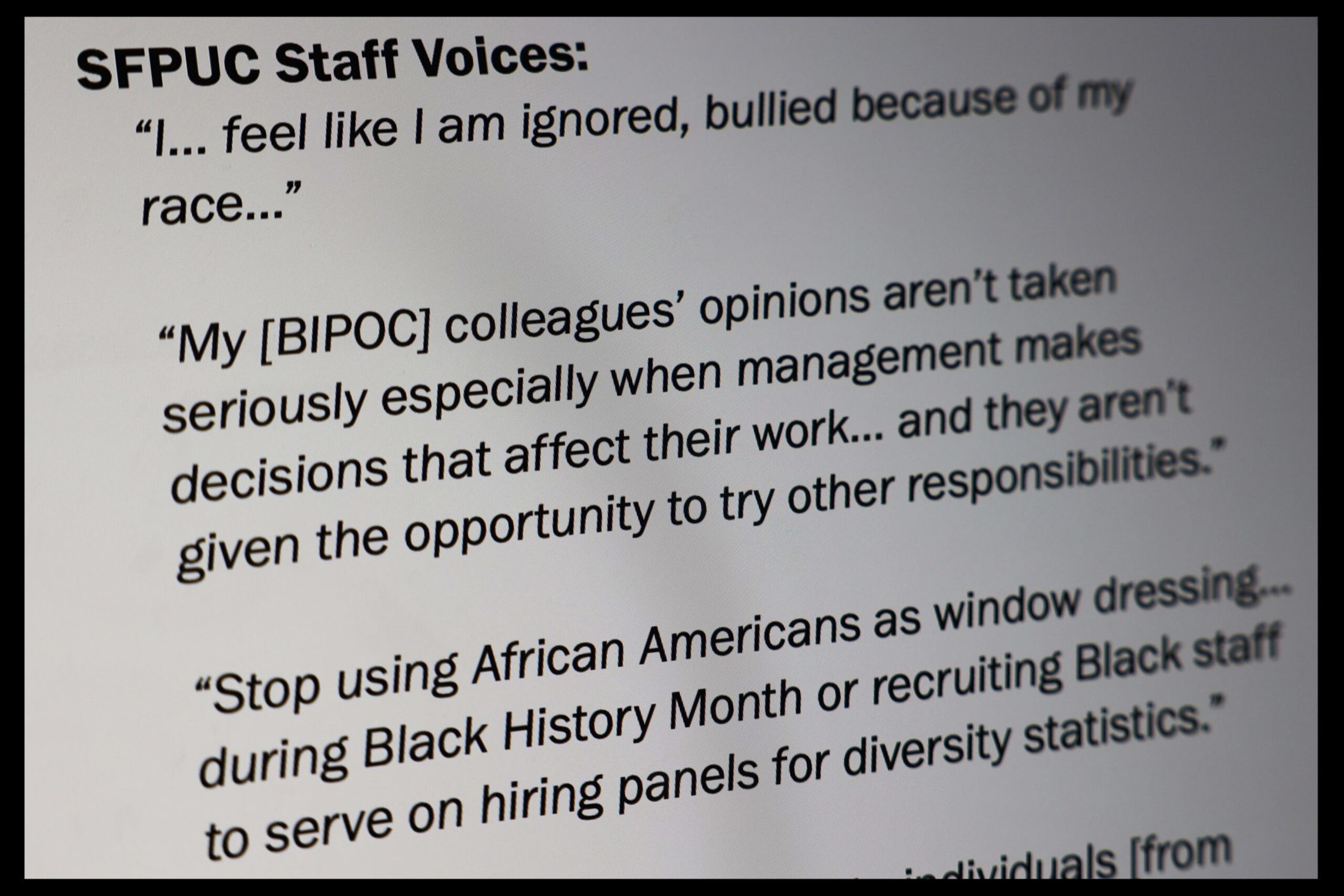

Government-wide staff surveys, which are required as an early step in the Equity Initiative, showed nearly every department split between white and Asian respondents who believed things were more or less fair, and Black and Latino respondents who believed their ethnicity put them at a disadvantage.

Cheryl Thornton, who has worked for the Department of Public Health for more than two decades, helped her department come up with racial equity plans. She said the need is great, but progress has been minimal.

“You have employees who are qualified, and all you have to do is offer mentorship,” Thornton said. “But there’s no mentorship.”

That department has submitted its equity plan. But once it was done and submitted, equity-related work came to an end, she said.

“They sent it to the board of supervisors. We haven’t had a meeting since, it’s been almost two years,” Thornton said.

Now Thornton is suing the health department, saying she, too, has been passed up for a promotion due to race.

In response to an inquiry, the health department said it does not comment on ongoing lawsuits.