At first blush, Dr. Ari Rubin was a mensch.

The Harvard-educated, “proudly Jewish” epidemiologist looked like a passionate progressive who used his Twitter account to support Ukraine, Black Lives Matter and the LGBTQ+ community.

He also had a blue checkmark, which traditionally meant the platform had “verified” his account and considered him a noteworthy person.

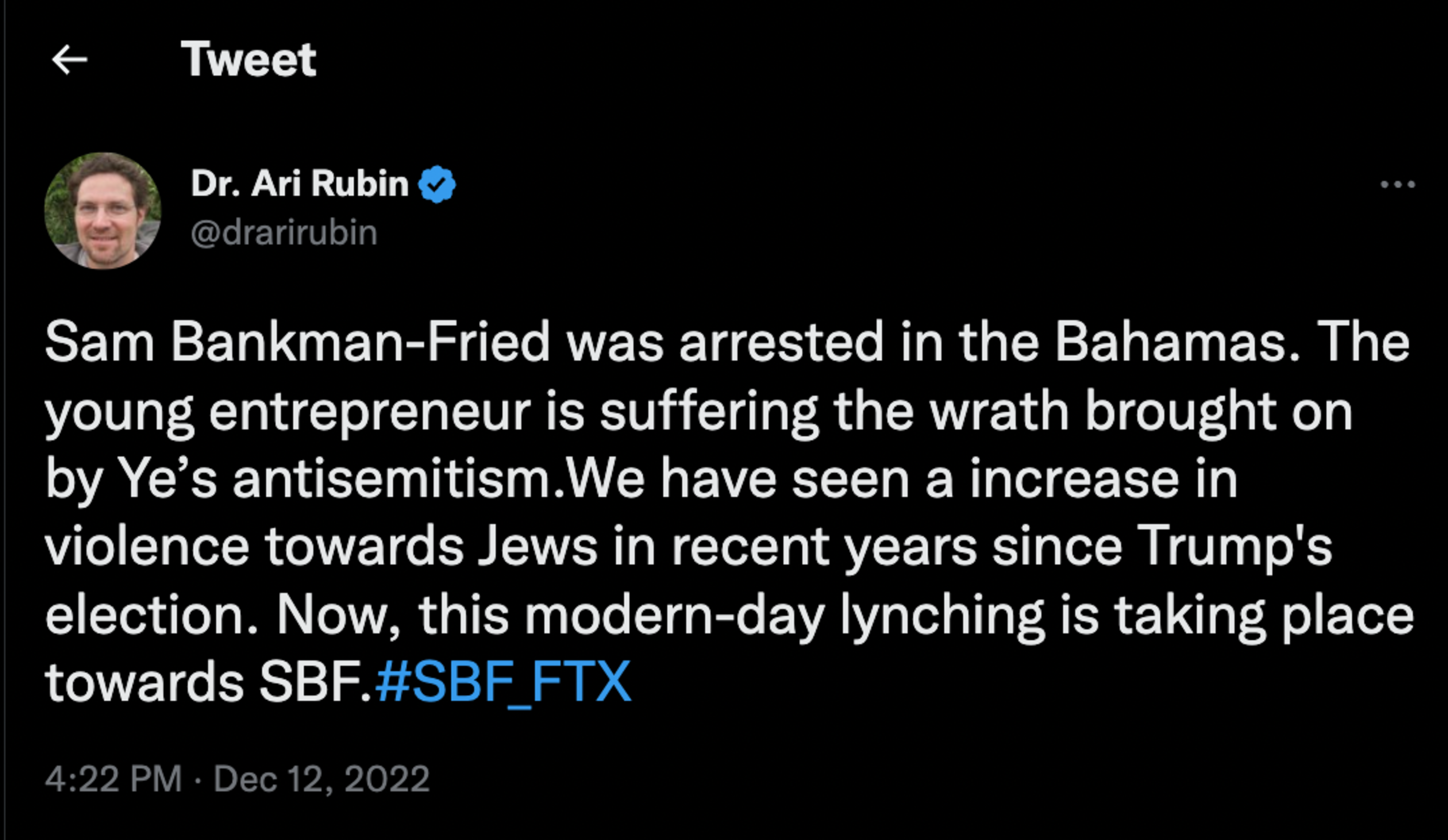

Then Rubin did something strange. He called the prosecution of Sam Bankman-Fried, the disgraced founder of cryptocurrency exchange FTX, a “modern-day lynching” provoked by rapper Kanye West’s antisemitism. That claim seemed so absurd that people started to doubt it could be an authentic human opinion.

They were right.

Rubin didn’t exist. His Twitter account aimed to provoke right-wing outrage against liberals, Jews and others with over-the-top progressive hot takes and offensive falsehoods.

And his blue checkmark? He only got the “verification” as a paid subscriber of Twitter Blue, a controversial feature implemented last month by CEO Elon Musk.

To critics of the mercurial billionaire, Rubin could easily be the face of the new Twitter: a disinformation agent who used the platform to advance offensive views.

Since Musk took the helm of the company in October, many users feel the social network has increasingly become a place of unrestrained falsehoods. Most prominently, singer Elton John abandoned the bird app (opens in new tab) over a “recent change in policy which will allow misinformation to flourish unchecked.”

But is disinformation—an endemic illness of social media—actually getting worse?

The news from Twitter doesn’t look good. But according to Renée DiResta, a research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, it’s impossible to say. Over the last five years, researchers like her have increasingly relied on communication and collaboration with Twitter’s moderators to study the issue.

“There came to be a realization that we were all on the same team about not wanting state-sponsored interference in elections, mass manipulation campaigns or mass spam campaigns,” she said.

Under Musk, the company’s staff has been decimated by layoffs and resignations. And that collaboration no longer exists.

“I think a lot of the members of that team are gone,” DiResta said.

A request for comment to Twitter Comms went unanswered.

Then and Now

Since becoming “Chief Twit,” Musk has done little to inspire confidence in the platform’s commitment to fighting dangerous disinformation.

He reinstated a slew of people who were suspended for hate speech, falsehoods or inciting violence. They included everyone from former President Donald Trump to rapper Kanye West and Andrew Anglin, the founder of the neo-Nazi website The Daily Stormer. (West was later suspended again after posting an image that combined the Nazi swastika with the Jewish Star of David.)

The new Twitter Blue, available for a monthly subscription of $7.99, initially allowed users to easily get blue checkmarks and impersonate public figures and companies. In one case, a Twitter Blue user posing as pharmaceutical manufacturer Eli Lilly tweeted: “We are excited to announce insulin is free now.” Share prices subsequently tumbled.

Even more alarming to many, Twitter announced it would stop enforcing its policy against Covid-19 misinformation. It was a distinctly Muskian move.

“Elon Musk appears to have a personal antipathy towards those kinds of measures,” said David Thiel, chief technologist of the Stanford Internet Observatory. “He was quite loudly and publicly wrong about the pandemic in the early days.”

The billionaire’s short-lived decision to suspend several journalists who reported critically on his ownership of the company also left many worried.

But while those changes appear to pull the muzzle off disinformation, there are several challenges to measuring whether it has actually increased across the platform.

First, any attempt to compare pre- and post-Musk Twitter will suffer from what DiResta terms a “recency bias”: Many of the older inauthentic accounts have already been taken down. This creates the appearance that there are more bad actors now than in the past.

Second, some of the inauthentic accounts active today were created before Musk took control of Twitter.

Here Rubin offers an instructive example.

The fake doctor’s account was registered in October 2021. Even early on, there were clear signs he was not who he claimed to be. Google searches yield no evidence of a Harvard-educated epidemiologist by the name Ari Rubin. His realistic profile photo was likely generated by AI. And his tweets often veered into the territory of provocation.

He called for mass immigration from Afghanistan, NATO intervention to support Ukraine and U.S. military “boots on the ground” in Qatar to protect LGBTQ+ people. He praised Anthony Fauci and transgender healthcare for young children—both political lightning rods on the right.

So Rubin was definitely not a product of Musk’s Twitter. But he still became its beneficiary.

By subscribing to Twitter Blue and receiving a blue checkmark, he was able to grant himself a veneer of legitimacy—at least to people who didn’t look too closely.

It might have helped him, too—had he not gone too far with his tweet about Bankman-Fried. Soon thereafter, his account was suspended for violating Twitter rules. An Instagram account in Rubin’s name was subsequently made private and then removed.

Messages to Rubin’s Twitter account before it was suspended and to a less active Reddit account in his name went unanswered. The Reddit account was later deleted.

Twitter Investigates Itself

Inauthentic accounts and spam bots aren’t the only measure of disinformation, according to Sara Aniano, who researches the subject at the Anti-Defamation League.

She is concerned about the reliability of the so-called Twitter Files, internal communications and documents the company passed to several journalists with notable antipathy for establishment liberals.

Their investigations from the documents, often published as threads on the platform, have focused on subjects like Twitter’s brief, polarizing decision to block a New York Post story about Hunter Biden’s laptop (opens in new tab); the rationale for suspending Donald Trump’s account (opens in new tab) after Jan. 6, 2021; the company’s communication with the FBI; and how it moderated controversial right-wing accounts.

Reception has been mixed, with some right-leaning individuals feeling vindicated, but many journalists and commentators finding the files unremarkable or overhyped. Kayvon Beykpour, Twitter’s former head of product, called some characterizations (opens in new tab) of the company’s moderation policies lazy or deliberately misleading.

Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s former CEO, wrote that he wished the documents were released publicly, “Wikileaks-style,” and not handed to a select group of journalists. “There’s nothing to hide … only a lot to learn from,” he wrote (opens in new tab).

Aniano thinks some of the reporting from the files is not entirely accurate. More alarmingly, it’s also “sending a message to more extreme groups outside of Twitter that spreading disinformation narratives is okay,” she said. “And obviously that’s when we start to get worried.”

But the biggest criticism of the files is more mundane.

“Speaking as someone who’s seen various companies’ trust-and-safety operations from the inside, much of it is just quite unsurprising,” said Stanford Internet Observatory’s Thiel, “and it’s the kind of thing that, if you were working in the field, you would expect.”

Though the files show Twitter communicating with the U.S. government, the company was likely talking with civil society organizations as well. And Thiel believes it takes that kind of communication to run a decent trust-and-safety operation.

That department can’t be hermetically sealed inside the company, he added, and “people are drawing some conclusions that don’t make a ton of sense.”