San Francisco has long been a proving ground for new technologies. But in the case of robotaxis, that can cut both ways.

Cruise and Waymo robotaxis are moving closer to regulatory approval in San Francisco, with state commissioners poised to allow 24/7 deployment later this month. But city officials are raising the alarm about episodes where self-driving cars have interfered with emergency services or obstructed traffic and public transit.

In one recent incident, a Waymo hit and killed a dog that was running off-leash. In another, a firefighter smashed the window of a Cruise vehicle to stop it from edging into an emergency scene. Despite these issues, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) appears to be at the cusp of approving a near-unlimited deployment of Cruise and Waymo robotaxis in San Francisco as soon as this month.

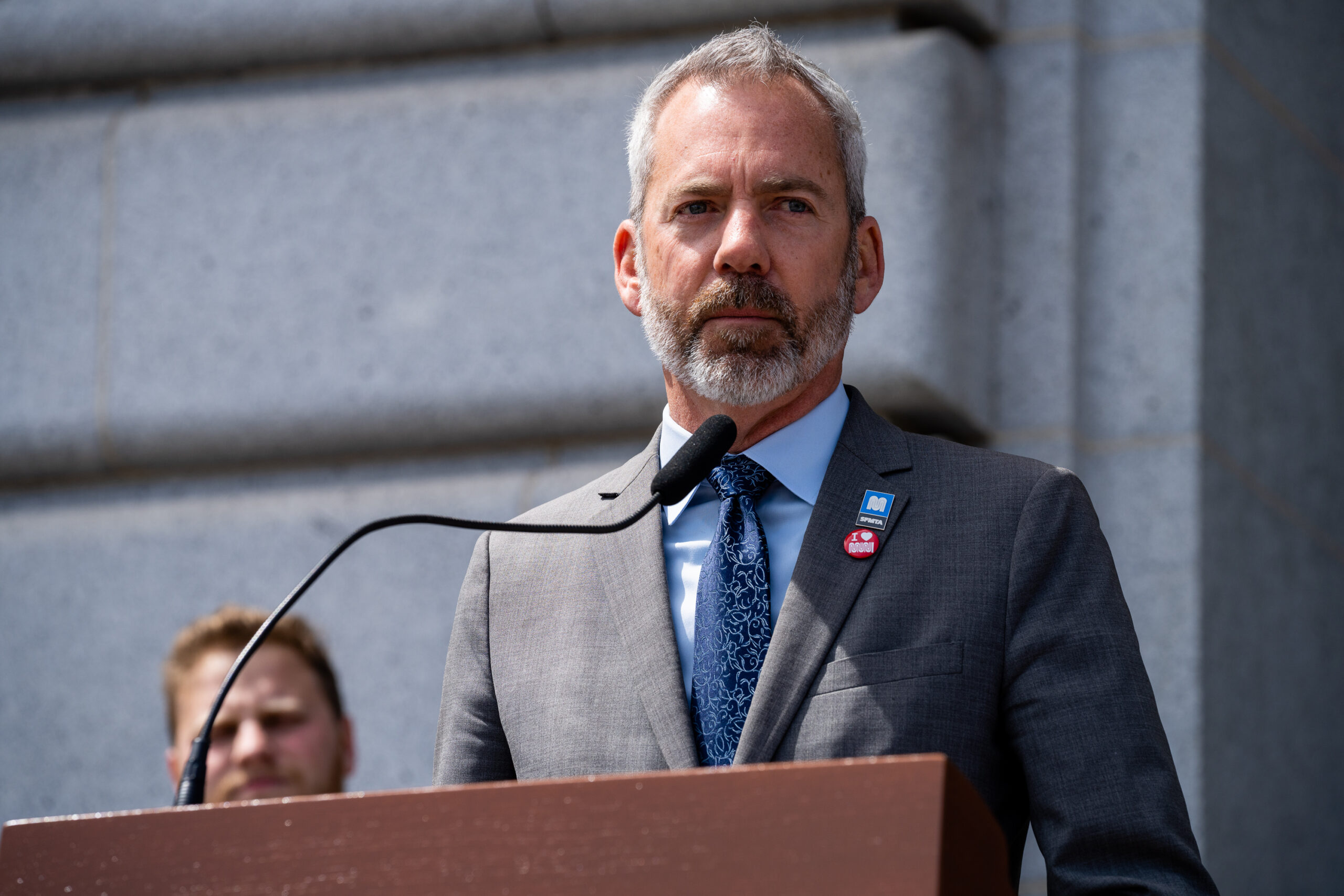

The fact that these technologies are largely regulated at the state level means that local officials have little recourse other than lodging vociferous protests. In an interview, San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Director of Transportation Jeffrey Tumlin explained why he and other San Francisco officials have taken such a firm stance against the current pace of the robotaxi rollout.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The utilities commission writes that it is encouraged by Cruise’s and Waymo’s safety records, but it appears that San Francisco officials disagree with that assessment. Can you explain that mismatch?

Part of our challenge is that we do not get any relevant data from either Cruise or Waymo.

We’re dependent upon the very limited data reporting that they make to the CPUC. Cruise and Waymo seem focused on avoiding injury collisions directly but do not seem concerned about the intensity of the chaos that they’re creating around them, like delays to emergency response times, the opening of passenger doors into the bike lane or other factors that may result in safety problems. Moreover, Cruise in particular has strongly promoted their safety record, but based upon the data that we have available, it appears that a Cruise vehicle is 6.3 times more dangerous than a human driver at this stage.

Part of the utilities commission’s argument for approving the companies’ deployment is that they meet the minimum standards. It seems like you don’t agree with that rationale.

I would argue that Cruise and Waymo have met the requirements for a learner’s permit, but they have not yet met the minimum requirements that a human driver would face for an actual driver’s license.

We’re eager to partner with them to help them advance their technology to the point where they are exceeding the safety record of human drivers. They are, however, a long way away from achieving that goal.

In part due to the protests lodged by San Francisco officials, the utilities commission has called for expedited rule-making on data-sharing from robotaxi companies. Would this be enough to gain your support for wider deployment?

Data is one of the most important factors that we need for judging the safety of any type of transportation. We are eager for CPUC to complete their new data reporting rule-making, and we believe that any additional authorization of AV deployment should be deferred until that rule-making is complete. How will we know if these vehicles are, in fact, meeting their safety goals if we don’t have relevant data?

How would you characterize the state’s regulatory posture to these self-driving car services up to this point?

The state’s regulatory structures are designed to solve the problems of the mid-20th century. The Department of Motor Vehicles determines whether a driver has the skills to be able to safely operate a motor vehicle, the federal government regulates the vehicle itself and the CPUC regulates the operation of passenger services. Our challenge is that all three of those functions, which used to be separate, are now in one integrated autonomous vehicle service.

DMV had the first regulations around autonomous vehicles in the country. At the time, those regulations were quite clever, but we’ve learned a lot in the last several years about unintended negative consequences. For example, we didn’t anticipate the delays to emergency response time. When a human driver gets confused, they will find a place to pull over safely on the side of the road and sort things out, whereas when an autonomous vehicle gets confused, it just comes to a complete stop wherever it happens to be. If that happens to be in front of a fire station or in the middle of an arterial intersection, that creates some pretty significant traffic and safety problems.

Similarly, DMV did not anticipate an autonomous vehicle needing to understand a human traffic-control officer directing traffic or understand firefighters at a fire scene. As it turns out, autonomous vehicles are having a really hard time with very common situations that the industry still calls edge cases but are ubiquitous in urban places like San Francisco.

Is there a plan in the works to use technology to mitigate some of these obstruction issues?

We believe that technology can solve all of these problems. However, unless the industry is compelled to solve them, we worry that there will actually be a race to the bottom. Right now, what we’re observing is industry players competing very aggressively for venture capital investments, which means very rapid expansion and the cutting of corners around safety performance. What we’re eager to see is a regulatory platform that provides a level playing field for technology to develop very rapidly but one that prioritizes safety and service quality.

We are particularly eager to partner with industry to maximize the amount of use of the curb so vehicles would pull to the curb for passengers rather than doing it in the traffic lane. There’s lots of available technologies around digitizing the curb. There are also approaches to safety measurement ubiquitous in the trucking or taxi industries that are not just waiting for people to be injured or dying—factors like sudden braking or acceleration, sharp corners, interaction with the bike lane, interaction with other vehicles. What’s amazing with autonomous vehicles is the amount of data that they’re collecting would allow us to collect an unprecedented amount of information about not only the direct safety issues associated with the vehicle itself but also the safety issues it is contributing to the rest of the mobility system.

There are some people that say you and your cohort are invested in protecting the incumbent system and human drivers regularly make many of the same mistakes as self-driving cars. How would you respond?

No, we want the transportation system as a whole to work. I don’t care whether people are taking autonomous vehicles or Uber and Lyft. I want my streets to be able to move more people more efficiently. I want to maximize safety outcomes, especially for the most vulnerable users of the roadway. I want to be able to increase mobility for all San Franciscans, but particularly mobility for those with the fewest choices, and I want to eliminate our greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector. I’m not partisan to any particular mode. But there are very specific quantitative ways by which we can measure all four of those key criteria. Right now, autonomous vehicles are failing at all four.

Let’s say the utilities commission does approve the deployment and the switch is flipped. What’s your nightmare scenario of what happens?

We know from our experience with Uber and Lyft that AVs will significantly worsen traffic congestion in San Francisco. Even at their most efficient deployment, they’ll still be creating a net increase in per capita vehicle miles traveled. There are ways of solving that, but the solutions to that problem are contrary to AV company’s financial model. We’re more concerned about worsening safety outcomes. While I believe that, at some point, AVs will be safer than human drivers, right now, that’s not the case. A concern I have given the poor safety track record so far is we’re on a path that will inevitably result in severe injuries and or fatalities, and that puts the entire industry at risk.