Back in 2008, when Balgobind Jaiswal purchased the Clay Theatre on Fillmore Street, he had no interest in running a cinema. He was after the retail space next door. But the previous property owner wouldn’t sell the buildings separately, so he ended up buying both.

Unfortunately for Jaiswal, what he figured was a smart investment has become a vexing financial burden. Though a tenant operated a movie theater out of the space for the first 12 years of Jaiswal’s ownership, they stopped paying rent prior to the pandemic and pulled out of the space entirely at the beginning of 2020.

Today, the space Jaiswal originally wanted is leased by the boutique clothing chain Alice + Olivia (opens in new tab). However, he can’t find anyone interested in overhauling the rundown theater and screening movies there. And a proposal targeting the Clay’s preservation, which is slated to come before the Board of Supervisors next month, may make the search even harder.

On March 9, the city’s Historic Preservation Commission (opens in new tab) voted unanimously in favor of bringing the century-old Clay under the protection of San Francisco’s Landmark Designation Program (opens in new tab), which is intended to “protect, preserve, enhance and encourage continued utilization … of significant cultural resources.” On April 11, the Land Use and Transportation Committee will consider the recommendation. From there, it will go to the Board of Supervisors for final approval.

“The Clay Theatre has been one of the most accessible and beloved cultural institutions in the Fillmore neighborhood for nearly a century,” said Supervisor Catherine Stefani, who initiated the Landmark Designation process for the Clay. “The landmarking process will allow us to preserve its unique character and to potentially reactivate the space for the community.”

For those who have followed the history of single-screen neighborhood theaters in San Francisco, this is a familiar refrain: In their attempts to prevent the destruction or dilution of community resources with high sentimental value, the city’s historical preservation apparatus has done just enough to keep a deep-pocketed developer from knocking down the Clay or turning it into something other than a theater—but not enough to guarantee it can continue screening first-run foreign films and midnight showings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Once a building receives landmark designation, it must abide by the 10 standards for rehabilitation (opens in new tab) outlined by the United States Secretary of the Interior, which dictates that repurposed historical structures may undergo only “minimal change to the defining characteristics of a building.” While Jaiswal plans to keep the antique features of the building intact, he has been waiting for almost two years for a change of use permit. The landmark designation will most likely extend his wait time.

Jaiswal has also been searching for a buyer, but he can’t find anyone willing to shell out the $6.5 million he believes is a fair market value for the Clay. He says he purchased the building for $4.8 million back in 2008 and has sunk almost $1.5 million into it in lost rent. At this point, he says he just wants to recoup his investment.

The San Francisco Neighborhood Theater Foundation (opens in new tab) tried to buy the theater before the pandemic for $3.5 million. “We believe this was a very competitive, market-driven offer,” Alfonso Felder, head of the Neighborhood Theater Foundation, told The Standard, adding that the nearby Vogue Theater had sold for $1 million. “We don’t know why it wasn’t accepted, but it was very disappointing to us.”

Felder isn’t the only one anxious about the Clay’s future. “There is tremendous community support for keeping it as a theater,” said Lynne Newhouse Segal, who is on the Board of Directors for the Pacific Heights Residents Association. “It was a center of our community,” she continued, recalling the great sadness when the theater’s seats were hauled out in the middle of the night.

And yet, even as city officials and passionate neighborhood preservationists agree that the century-old building is culturally significant, no one in the community is stepping up.

A Beautiful Ruin

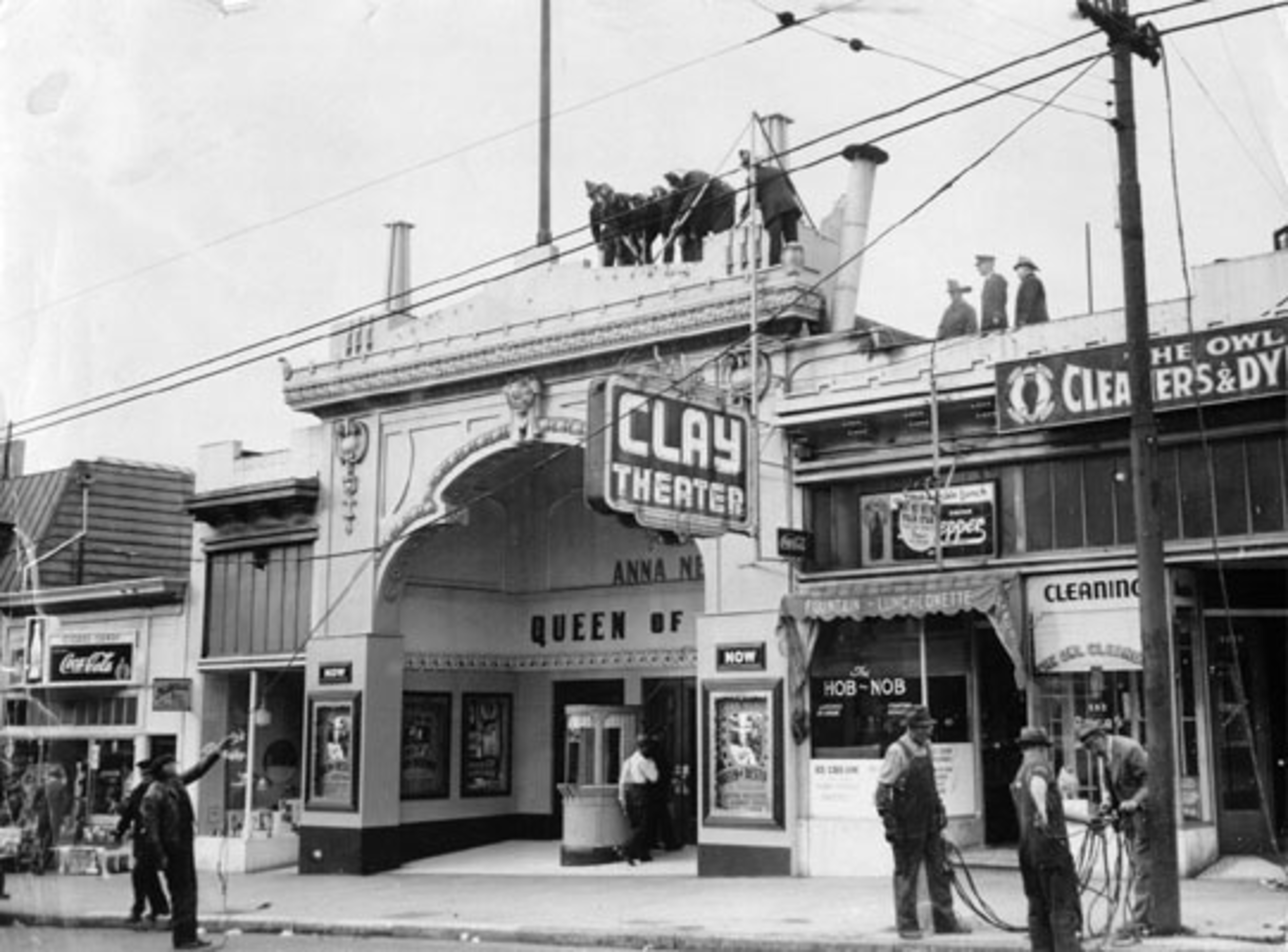

In the early 1910s, as many as 26 million people attended nickelodeons (opens in new tab) like the Clay every week, according to film historian Maggie Valentine. These early theaters would show up to 18 screenings a day, seven days a week. With its recessed entryway, plaster ornamentation and shaped parapet, the Clay—which opened on the southwest corner of Fillmore and Clay streets in 1913—is emblematic of an early 20th-century neighborhood cinema.

This history is certainly part of the Clay’s appeal. Locals like Grant Villeneuve have a strong attachment to the theater, which they see as part of the city’s cultural legacy. Villeneuve began the Save the Clay organization in spring of 2021 with the aim of ensuring the theater’s preservation. “A lot of it has to do with the soul of Fillmore Street and, by extension, the city and sense of place,” Villeneuve said.

Jonathan Ayres, who lives and previously worked in the neighborhood, fondly recalled many of the films he watched at the Clay: Europa Europa, Still Alice, Julieta, Leviathan. “The movies you saw there had an impact and stayed with you,” Ayres said. “The theater was an aesthetic equal to the film you were watching—it was a fitting temple.”

“It’s a no-brainer for a city landmark,” said Woody LaBounty, executive director of SF Heritage (opens in new tab), a local nonprofit dedicated to preserving and enhancing the architecture and cultural identity of the city. “It’s got architecture, it’s got cultural relevance and it’s got great historic integrity to convey part of the city’s past.”

But even if the historical significance of the theater is undisputed, the economic viability of a single-screen theater in 2022 is up for debate. As many as eight single-screen theaters have vanished from San Francisco over the past 30 years.

The film industry—like any industry—has always been at the whim of changes in consumer demand and technological disruption. Single-screen nickelodeons lost some of their market share to the rise of multiscreen movie palaces in the 1920s. In response, some neighborhood cinemas like the Clay carved out a niche to differentiate themselves.

In 1935 the theater became the Clay International, the first cinema dedicated to foreign films in San Francisco. Later on, as multiscreen cinema palaces ballooned into massive megaplexes, the Clay honed its specialty identity further—drawing dedicated cinephiles by focusing on independent films and communal midnight screenings.

Sentimentality vs. Practicality

Over the past 14 years, Jaiswal has had a front-row seat to another massive shift in the movie industry, as the ubiquity of streaming services and affordable home entertainment systems have drawn viewers away from public theaters of all stripes. Near the end of their tenancy, the Clay’s previous leaseholders, Landmark Theaters (opens in new tab)—a national chain, which specializes in independent and foreign arthouse films—had gone years without paying rent

“We spent several years and hundreds of thousands of dollars trying to keep it as a theater,” the landlord said. Landmark continued paying for property taxes, insurance and occasional repairs, Jaiswal paid for the rest.

When the theater officially closed in January of 2020, Jaiswal—believing there was little business case for running a cinema out of the run-down single-screen theater—applied for a change of use permit, which has yet to be approved. In the meantime, the building has fallen into such disrepair it’s scaring away potential buyers and leaseholders.

“Inside it’s really, really, really bad,” Jaiswal said. “Almost to the point you’re afraid to go into the projection booth. It wouldn’t meet any of the building codes right now.”

David Marlatt of DNM Architecture has been working with Jaiswal on the Clay’s renovation and says he doesn’t see a future for the Clay as a theater.

“The small, single-screen movie theater is not really a viable business,” Marlatt said. “Our proposal to the planning department is to allow it to be converted from a movie theater to some sort of retail use, like a big art gallery or store of a different type.”

Others believe the Clay has the opportunity to be a viable business as a theater. “The Clay is this beautiful, small scale, jewel box of a theater that I feel does have a path forward economically,” LaBounty said.

Sign of the Times

When Another Planet Entertainment announced it would be taking over management and programming at the Castro Theatre, many were displeased. Passionate local film fans turned out for a protest against the new management (opens in new tab). Yet perhaps a plan to renovate and reimagine the space (opens in new tab) with the intent of turning a profit is better than shutting it down altogether.

Save the Clay founder Villeneuve is open to the idea of hybridizing the Clay and identified two paths forward for the theater. Either the city and preservationists work together and we “cross our fingers” for the future, or a wealthy benefactor gets on board to save the theater, knowing full well the economic challenges.

“I don’t think it could ever be a lucrative entrepreneurial thing,” Villeneuve said of the Clay.

Villeneuve is open to a change of use for the building, as long as film remains in the picture. He claims it could be a flexible space, rented out as an auditorium by schools or operated as a co-op theater. The historic Roxie Theater (opens in new tab) in the Mission is run as a nonprofit, supported by a host of grants as well as members and donors.

Whatever happens with the Clay, Jaiswal says he hopes it happens soon, as maintaining the empty theater is coming at a “tremendous cost” to him, his family and his retirement plan. But he isn’t holding his breath. “The city moves at the pace of a snail,” Jaiswal said with a weary chuckle.

As a businessman, Jaiswal seems genuinely baffled that the community would rather keep the Clay as a single-screen theater—clearly an unviable business model in his view—than see it become something else. By his estimation, a successful business running out of the building would generate close to half a million dollars in tax revenue for the city each year.

Still, he says he wouldn’t really care what the city—or any future owner—did with the building, as long as he was compensated fairly. “If they want to keep the theater for society and the neighborhood, then they should pay for it,” he said.

In the meantime, Jaiswal said, all he can do is wait and see what the Land Use Committee and then the Board of Supervisors decides. And the Clay will be right there with him—waiting.

“Basically it will just stay empty,” he said. “What else could happen?”