If you look up San Francisco’s directory of legacy businesses (opens in new tab)—a city certification meant to celebrate and support longstanding neighborhood institutions—the very first entry on the list is Eros.

A venue for sexual exploration and safe-sex education tailored to the city’s gay community, it originally opened in the Castro in 1992. Outside of providing clean and sex-positive spaces, the organization also operated a number of community-serving spaces like an art gallery, community classroom and a massage room.

But after the business’ longtime landlord died and his family sold the property to a new owner, Eros CEO and co-owner Ken Rowe said the writing was on the wall. Covid-era restrictions on indoor gatherings spurred him to begin searching for a new space in earnest.

“If you look at the model of what happened to the city and the country after the Spanish flu…all of a sudden there was a bounceback in the Roaring Twenties,” Rowe said. “So it’s hard not to kind of expect that, even in the back of your mind.”

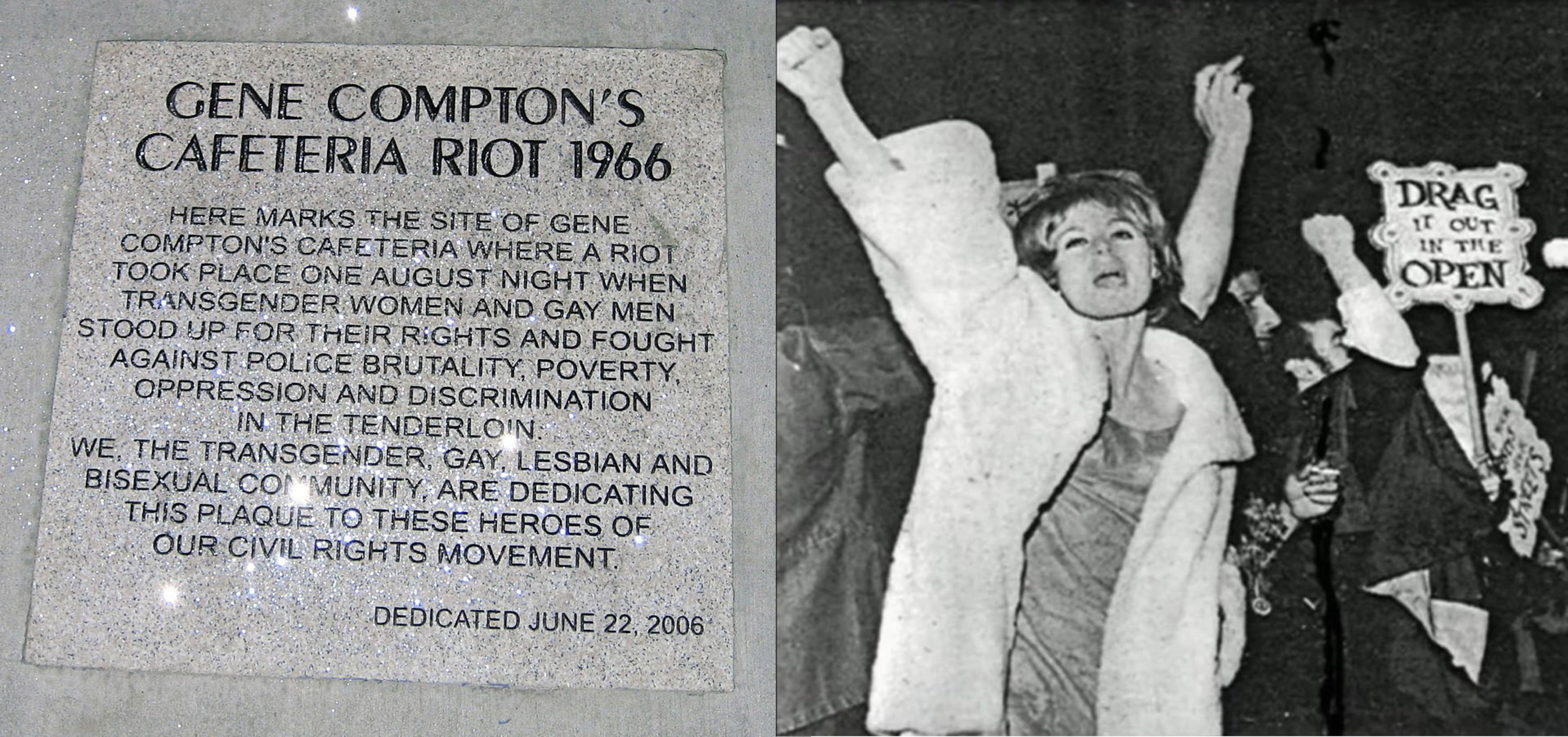

Most inquiries with potential landlords were met with silence or harried excuses, but eventually the Eros team centered on what seemed like the perfect location: a 4,000-square-foot space at 132 Turk St. in the Tenderloin owned by a gay man who was seeking to fill the space with queer-owned businesses that could serve the community. The location itself is smack dab in the middle of San Francisco’s Transgender Cultural District, and down the block from the site of the Compton’s Cafeteria riot, a 1966 act of LGBTQ+ civil resistance that preceded the Stonewall riots by three years.

“I just wanted to revive the historic use of the building and bring back a little more gay to this neighborhood,” said David Nale, the building’s owner.

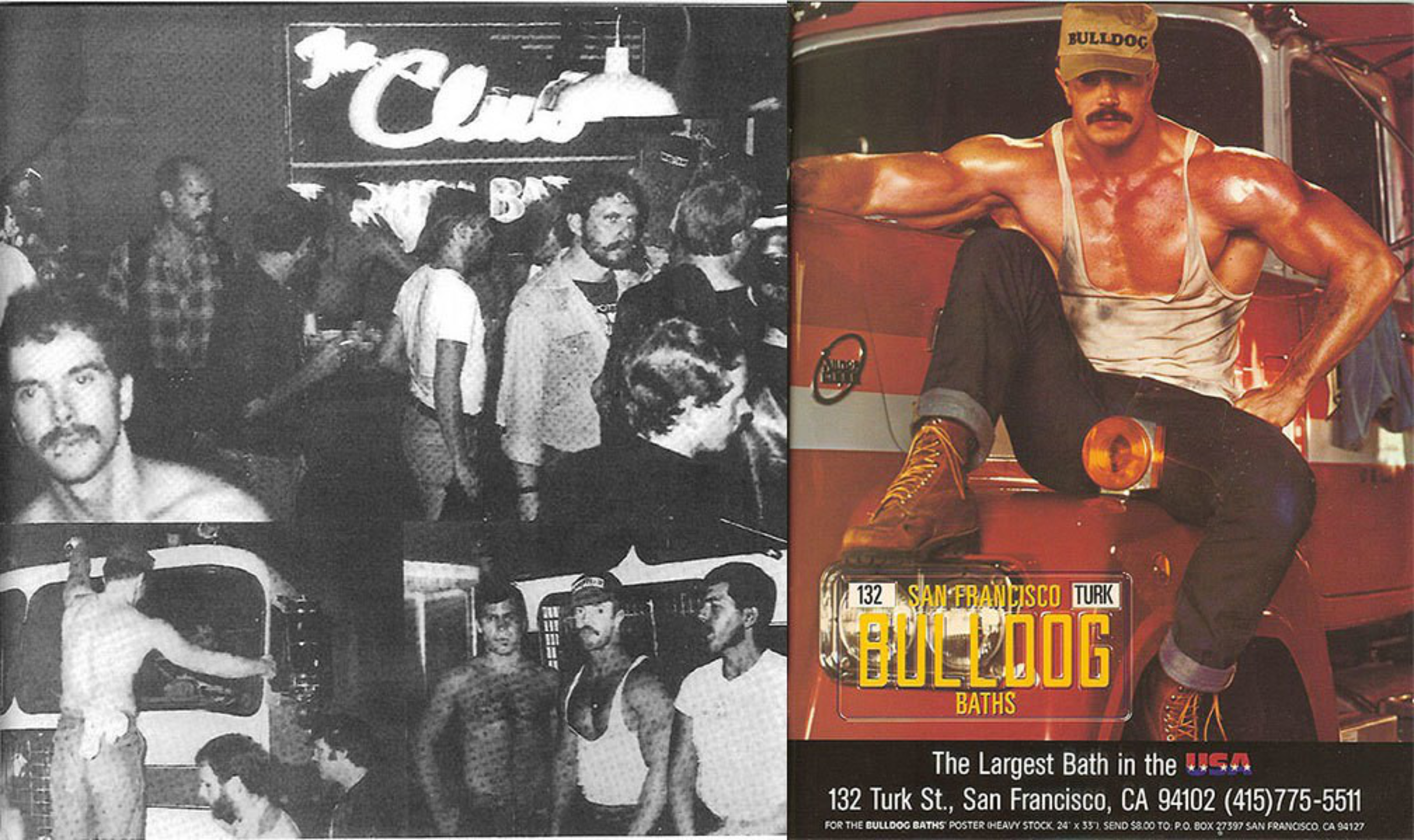

What’s more, the location had been a bathhouse and venue for sex for most of the 20th century. It was originally known as the Club Turkish Bath House, San Francisco’s first-ever gay bathhouse. Then it became the legendary Bulldog Baths, which was billed as the largest bathhouse in the country, until then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein shut down all such facilities (opens in new tab) in the city as HIV/AIDS was spreading through the gay community.

The connections go even further. In fact, the founders of Eros had helped to remove the historic murals inside Bulldog Baths for preservation.

“It’s a good spin on the story,” Rowe said of the site’s historical significance. “It’s the hook.”

But in a classic San Francisco twist, zoning restrictions meant that Eros was blocked from operating at the space because adult businesses are generally not permitted to operate in many parts of the city.

Eros worked with Supervisor Rafael Mandelman to introduce legislation that would define bathhouses and sex clubs like Eros as “Adult Sex Venues” in the planning code and allow them to operate 24/7 in select areas that overlap with established LGBTQ+ cultural districts including the Transgender Cultural District, the Castro LGBTQ+ Cultural District and the Leather and LGBTQ+ Cultural District in SoMa.

“This is one of the situations where our code doesn’t line up with anyone’s reasonable expectations with how the world would work,” Mandelman said. “I don’t think there’s any person at the Planning Department that agrees with them, but we have these archaic provisions in the planning code that need to be fixed.”

The Planning Commission unanimously approved the ordinance on April 7, and it’s now scheduled to be heard by the Board of Supervisors Land Use and Transportation committee later this month. Ultimately, Rowe hopes this will pave the way for the business to open prior to the revived San Francisco Pride celebrations in June.

“It was never part of the equation that we would shut down the business,” Rowe said. “But if we knew how difficult this was all going to be, we would have saved a lot of money if did. Still, it’s just so exciting because the city feels like it’s at the cusp of being really, really alive.”

As of last Dec. 15, when Eros SF’s Castro location had its last day of operation, San Francisco

had no gay sex clubs operating inside its city limits, particularly after the pandemic led to the closure of some local competitors. Strange as that sounds in a city so tied to LGBTQ+ history and culture, the loss of entire generations of gay men to AIDS meant the businesses that catered to them disappeared as well.

That earlier pandemic sparked a debate within the community about bathhouses and sex clubs’ role in the spread of the virus. In 1984, the city filed lawsuits against a number of these venues, citing public health risks. A resultant court order required these businesses to institute monitors and policies to prevent unsafe sex.

While the suit was eventually dismissed a few years down the line, the new regulations led to a large-scale decline in these businesses in San Francisco.

“None of the clubs were willing to kind of roll with it and try to innovate within the rules. Other municipalities were able to do it, but they didn’t have those court orders like San Francisco did,” Rowe said.

Mandelman has been spearheading the effort to reintroduce clubs like Eros to San Francisco, starting with an ordinance introduced back in February 2020 that successfully overturned (opens in new tab) some of the public health rules introduced in the 1980s.

That initial legislation grew out of San Francisco’s relatively backward policies compared to other cities, particularly with the introduction of new forms of HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment like PEP and PrEP.

When other major American and international cities had those types of spaces, it felt particularly peculiar and wrong that San Francisco did not,” Mandelman said. “Allowing them to open could really be a catalyst for neighborhood economic development, for the resurgence of queer culture and establishing San Francisco again as a national and international destination for the community.”

Stephan Ferris, an attorney who specializes in queer entertainment businesses, said bathhouses and adult sex venues have long served as cultural spaces and access points for resources like STI testing and education.

Mandelman added the new loosening of restrictions could generate a new crop of entrepreneurs, people who will redefine what these types of venues can and should like.

“I’m not old enough to have participated in the heyday of bathhouse culture, but I’ve heard from folks about the great community-building they’ve had in bathhouses—not just as places to have sex, but places to have amazing conversations, meet up with friends and even take in a show,” Mandelman said. “Now there’s an opportunity to see how a queer bathhouse in 2022 looks different than a gay bathhouse in 1978 and that’s fantastic.”

As for Eros? Rowe said the business is hard at work building out a space that pays homage to the traditions built up over 30 years of operations, along with updates that appeal to changing customer demands. The business plans to have multiple locker rooms, a video pit, a series of play spaces and potentially a couple of semi-private rooms.

“The entrance is so narrow. It’s so grand and uplifting that people lose their breath when they walk in,” Rowe said of the new location. “There’s not a lot of gay institutions that have? lasted 30 years, and it feels good to be part of something that’s been around and plans on continuing on for the foreseeable future.”