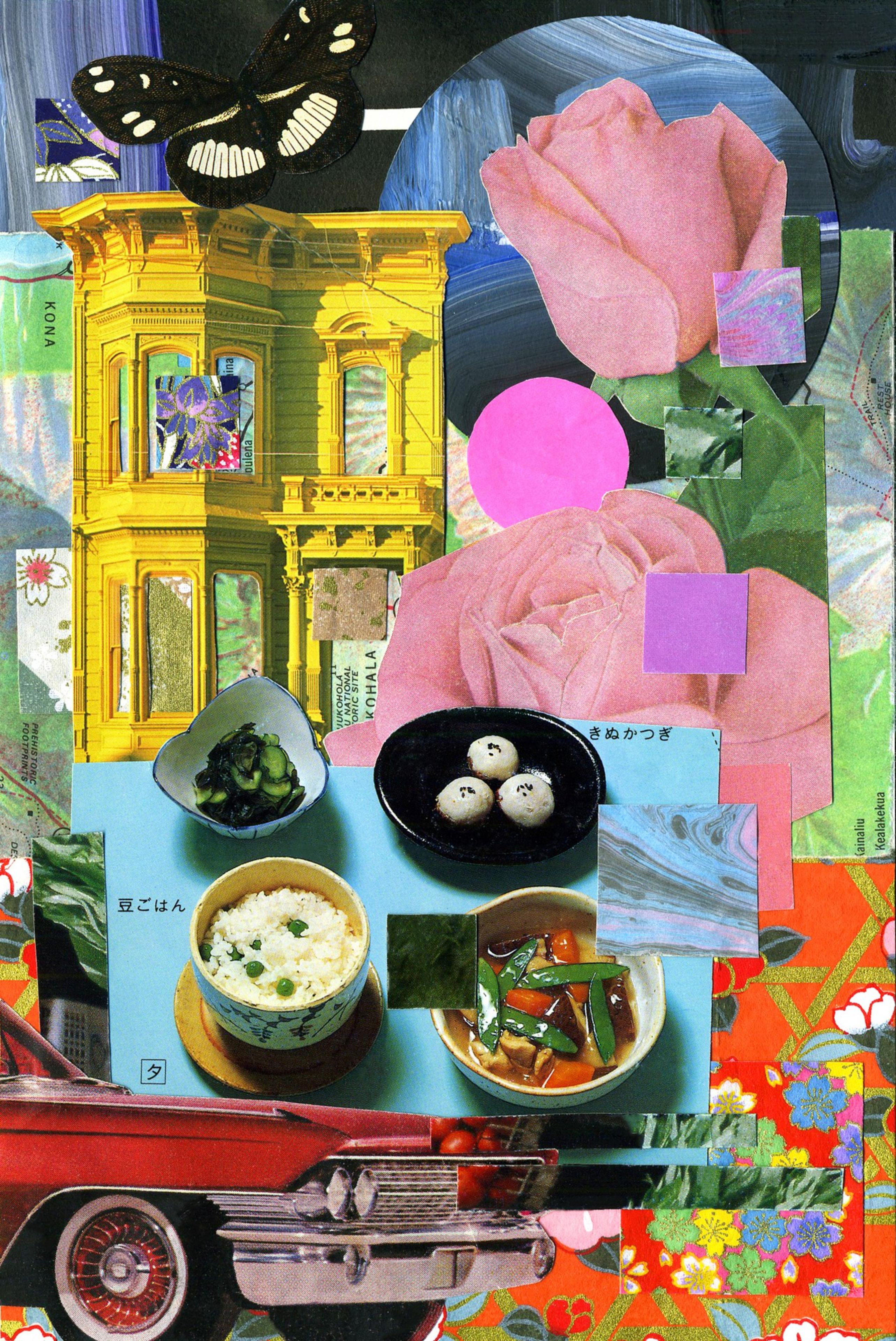

Collage artist Eryn Kimura (opens in new tab) is a fifth generation San Franciscan who uses vintage print media and decorative, handmade Japanese paper to create vivid collages aimed at dismantling orientalist depictions of Asian women.

In “Frisco Fauna,” the sleek, burgundy body of a 1970s Thunderbird passes through the profile of a geisha photographed by National Geographic in 1969. The windshield of the car assumes the shape of her lips, chin and forehead. A Muni bus transfer pokes out of her hair ornaments. Translucent leaves sprout from her kimono and engulf the image.

The collage is a work of personal and political significance. Kimura’s mother used to drive a ’70s Thunderbird around the city and Kimura views Muni as one of her most formative classrooms. She remembers how the old bus transfers required riders to travel within a strict time frame, which always made her think of them as a form of time travel.

“Anytime I show a form of transportation, it’s an homage or an understanding that we’re traveling into the future which is also the past,” Kimura said in an interview with The San Francisco Standard.

The collage artist has spent years cutting up images of San Francisco and gluing them back together again, capturing all the city’s nostalgic vibrance and volatile microclimates. She compares her creative process to being a DJ, remixing different images and visual fragments. The San Francisco that emerges from her collages is a city hurtling into the future even as it recycles the past.

Gallery of 1 photos

the slideshow

Kimura’s family has close ties to the Chinese American and Japanese American communities in the city that go back to the 19th Century. Her Chinese ancestors immigrated to the United States from Toisan, China, in the 1800s to work on the Transcontinental Railroad. Her Japanese side of the family ran a manju shop in Hiroshima before coming to California by way of Hawaii following the Second World War.

Kimura was raised in Japantown and attended Lowell High School—just like her parents who met there and became high school sweethearts. It was at Lowell that Kimura was first introduced to SCRAP (opens in new tab), a nonprofit depot that diverts recycled materials out of San Francisco’s waste stream and into public school art classes; She forages for materials and inspiration at the group’s Bayview warehouse.

Gallery of 1 photos

the slideshow

Back in her studio, she starts by ripping out photographs and sorting them by color, theme and object. She then cuts out the images and organizes them into little boxes, while wryly acknowledging that the images themselves can never truly be compartmentalized.

For Kimura, flipping through print media from the last hundred years is a way to imagine what her parents, grandparents and great-grandparents saw and experienced. It is not always an easy history to relive: Kimura sees her collages as a way to directly intervene in how Asian women are so often depicted in mainstream media.

Gallery of 1 photos

the slideshow

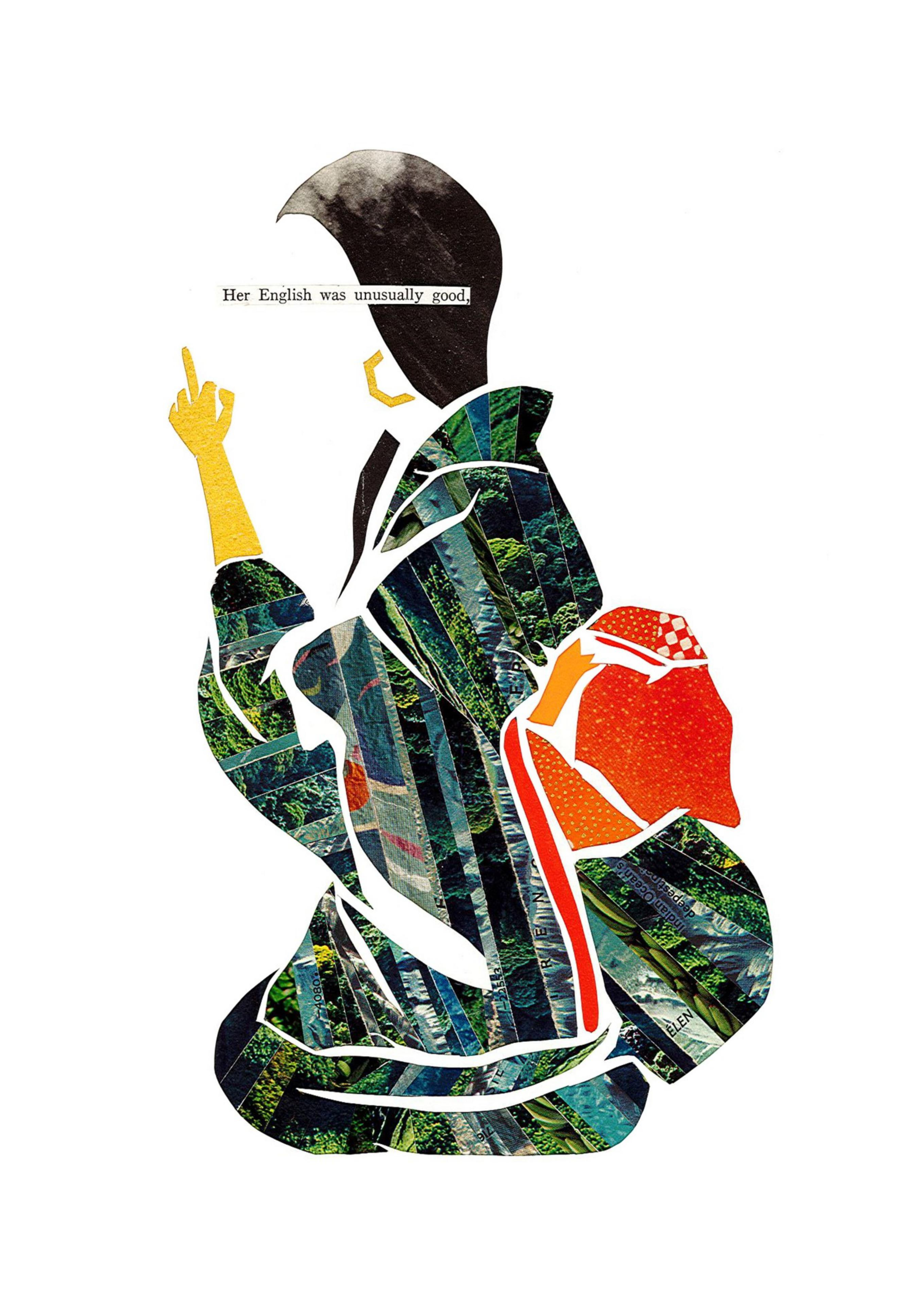

In the collage “her english was unusually good,” a faceless woman flips off the viewer while the title of the piece, lifted directly from a National Geographic article about Japan from the 1930s, runs across the negative space where her facial features should be. Although “her english was unusually good” could read as a complete sentence, Kimura retains the comma at the end of the phrase, leaving it an unfinished thought, a middle finger to linguistic hegemony.

The Golden Gate Bridge is another recurring motif in Kimura’s work and she likes to imagine it as Mazu, a Chinese sea goddess associated with safe passage and childbirth. Like the Golden Gate, Mazu is mythologized as wearing a red dress while roaming the seas.

“Mazu had the capacity to travel to the past and also to the future,” Kimura explained. “She protects people on their journey while also traversing the present and the past.”

Given that many of Kimura’s ancestors entered America through the mouth of the Bay long before the bridge was constructed, she considers the Golden Gate a personal Mazu.

“My family passed through safely,” Kimura said. “And we’re still here.”