The San Francisco Public Library has a little-known tagline: “Every library, every day.”

In the days before Covid, City Librarian Michael Lambert said this was an easy motto to stick to: each of the city’s 27 public library branches and its main library site opened seven days a week, serving thousands of San Franciscans with their reading and resource needs.

But with a global pandemic that shuttered public buildings and prohibited social gatherings, the last two years have been anything but typical for the San Francisco Public Library (SFPL).

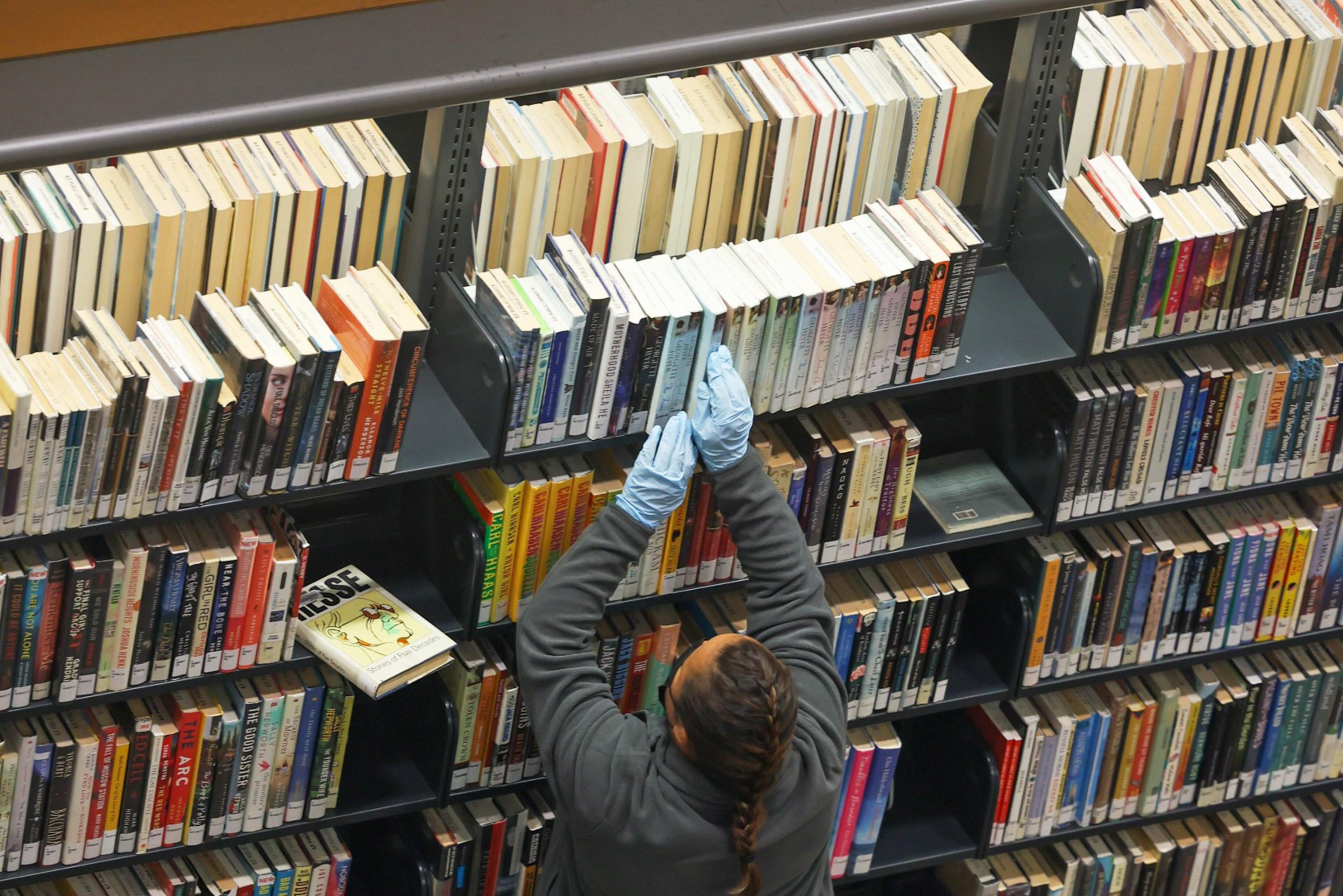

All SFPL branches closed for public use in March 2020, and remained closed for another 14 months. Programs came to a screeching halt early on, and recent in-person attendance has yet to reach pre-pandemic levels. Material circulation patterns changed dramatically during this time, and the city even employed two-thirds of the library’s staff (opens in new tab) as Disaster Service Workers.

“Pre-COVID, we would offer well over 15,000 programs, classes, and events a year, and we would draw half a million people that would come to the library just for these experiences. We’re not there yet,” said Lambert.

But in recent months, what looked like overwhelming challenges for SF’s main public learning institution turned into an opportunity for ongoing change and transformation—what Lambert says is a crucial turning point for the library in the wake of the pandemic.

“People don’t stop reading and didn’t stop reading,” said Randle McClure, SFPL’s Chief Analytics Officer. Even as the circulation of physical books and materials dwindled, the library saw other transformations in its operations: eMaterials shot up in popularity, virtual events became popular with patrons around the world, and the library found other ways to serve the community.

“That’s really a success story of ours throughout the pandemic: to be able to provide [services] even when our doors were closed,” said McClure.

The result? Things are looking up for SF’s libraries. Here are 5 trends that show SFPL programming strategies and circulation trends bode well for the future of the system.

1. What Goes Down Sometimes Comes Back Up

Though circulation during the pandemic was depressed, check-outs for the 2021-22 fiscal year show a promising recovery: McClure said that July 2022 was one the library’s highest in circulation since it started tracking data. And SFPL reported a total circulation of 11.2 million in the past year, nearing the all-time high of 11.7 million materials circulated in 2018-19.

“If [circulation] keeps up over the course of an entire fiscal year, we will eclipse 12 million circulation for a year, which would be our highest ever,” said McClure. “We’re feeling pretty good right now about our circulation with both physical and electronic [materials] being very robust.”

Circulation of physical and electronic materials went through what McClure described as a “volatile period”: while the library set an internal record of over 11.7 million items in circulation in the 2018-19 fiscal year, the pandemic decimated that number in 2019-20 and 2020-21.

Circulation of physical materials—such as hardback and paperback books, DVDs and magazines—dropped most dramatically, with a 74% decline in circulation between 2018 and 2021. This decline is largely due to the physical closure of SFPL’s branches and staffing shortages during the first year of the pandemic.

“This naturally has an impact on physical circulation if people can’t come into the building on certain days of the week—you know? That will depress circulation,” said Lambert, who assumed his position at the head (opens in new tab) of SFPL just a year before the pandemic hit in 2020.

Branch-specific circulation trends reflect this fact, showing an overall decline in circulation at nearly every single location.

But this data doesn’t show the whole picture, nor does it account for the fact that the library has, in fact, bounced back from its pandemic-induced circulation lull.

Not all libraries have reopened to full, seven-day, in-person operation, which directly affects circulation numbers. And other branches have faced site-specific challenges outside of pandemic-related closures, including staffing shortages and an institution-wide hiring freeze.

Though the Mission branch reports an 83% decline in circulation from 2018 to 2022, that location has been closed for renovations (opens in new tab) since 2021. Other sites with a high percent change in circulation—such as Ingleside and Visitacion Valley—have experienced similar interruptions to their physical operations.

In recent months, the majority of SFPL’s branches have opened fully. Just this past weekend, three branches opened up to full operating hours: Visitacion Valley, Ingleside and Glen Park. And Lambert anticipates that the final holdout, Noe Valley, will have its grand re-opening on October 1.

“Library utilization of our collections, both physical and digital, is happening in every neighborhood of San Francisco. Every neighborhood is accessing their library’s collections again,” said Lambert.

Indeed, branches in Bernal Heights and Eureka Valley both reported consistent end-of-year circulation numbers from 2018 to 2022. The Bernal Heights location even showed a modest increase in circulation, reflecting locals’ loyalty to SFPL: some library enthusiasts gathered on the Bernal Heights branch porch to use the free wifi and host socially-distanced happy hours in 2020.

But with more doors opening and services slowly creeping back up to pre-pandemic levels, library officials anticipate that overall circulation levels will recover and soon surpass pre-pandemic levels.

2. The “Revenge of Analog”

Though overall circulation numbers are trending upwards again, the makeup of SFPL’s circulation has changed dramatically.

The early pandemic was the era when TikTok was only dancing (opens in new tab), family meetings were held on Zoom calls, and everyone was chronically online. Turns out, that made for the perfect environment for the rise of online reading and eBooks.

Unsurprisingly, San Francisco’s libraries reported a sharp rise in electronic books and other digital material (called “eMedia” by SFPL) circulation since 2018, accelerating an upwards trend that started showing in circulation data from as early as 2013. The circulation of physical books and other materials (called “pCirc” by SFPL), on the other hand, all but dropped off during this period, and has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels.

National trends largely mirror (opens in new tab) what we see in SFPL’s data: overall circulation is collapsing in libraries across the country, and national eBook circulation doubled from 2019 to 2020, as physical book circulation dropped nearly 10%.

The rise of eMaterials and the fall of physical circulation is reflected in the types of materials that grew or fell in SFPL’s circulation from 2019 to 2022. eBooks and eAudiobooks shot up in popularity during this period, while circulation for museum and event passes dropped more than 60%.

In an unexpected twist, some more obscure physical materials experienced a surge in popularity over the last year.

Music lovers, for one, flip-flopped from CD-listening to MP3 playing and, now, back to old-school listening mediums. SFPL’s data shows that vinyl is back in fashion again, as the circulation of phonodiscs (catalog-speak for vinyl records) increased by 30.7% from 2019 to 2021—a trend that Lambert likes to call the “revenge of analog.” TikTok might be to blame (opens in new tab) for this one: vinyl grew in popularity during the pandemic and has recently become music’s most popular physical format (opens in new tab).

Spoken books—picture books that come with an accompanying CD audiobook—saw circulation skyrocket in 2022. With an astonishing 250% increase, these materials were especially popular among children and younger library patrons.

3. Kids Still Rule

If the previous statistic is anything to go by, then it’s clear that kids rule San Francisco’s public libraries.

SF’s libraries have a massive collection of children’s resources (opens in new tab), and before the pandemic, the majority of programming (opens in new tab) was geared toward younger patrons.

“Storytimes are our bread and butter: bringing in youth and families for that sense of wonderment and excitement about hearing stories, participating in sing-alongs and engaging with a children’s librarian,” said Lambert, himself a former children’s librarian.

Circulation data again reinforces this point: every single branch at SFPL shows juvenile materials—physical, electronic, graphic, picture or otherwise—within the top five most circulated types of materials. The library system even has an entire center at the main branch (opens in new tab) dedicated to children’s resources.

Yet, the pandemic complicated children’s access to libraries, even as some branches started opening up again. Parents and library staff expressed safety concerns for a return to fully in-person children’s programming, especially as the early Covid vaccines that enabled public gatherings for adults largely excluded children under the age of 12. And Covid’s impact on children had a clear ripple effect on their parents.

“As a parent myself, I come to story time. I’ll also browse books and check out a giant stack for our kids,” said SFPL Communications Director Kate Patterson. She notes that the library had to wait for vaccines to increase age availability, in order for parents to feel more comfortable and to revamp in-person programming.

Even as some families remain hesitant to return to in-person library events, circulation trends show kid’s books are just as popular as ever, and especially in certain branches: 17 of SFPL’s 28 branches show a children’s material circulation share greater than 50%, and the library’s Fisher Children’s Center dedicates 100% of its circulation to children’s materials.

Children’s materials account for nearly two-thirds of the Bernal Heights branch’s circulation—and they were the only branch to experience an increase in overall circulation from 2018 to 2022.

4. Libraries Aren’t Just About Books—and That’s a Good Thing

Though recent figures are promising, circulation data alone cannot paint the whole picture of how SF’s public libraries have adapted to pandemic conditions.

The number of people physically entering SFPL’s branches clearly plummeted during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, Lambert estimated that SFPL hosted well over 15,000 programs, classes and events per year, drawing in hundreds of thousands of people into library buildings.

Today, attendance for in-person and online events still has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels, though numbers are rising again.

Library staff believe these changes in circulation or branch attendance are not necessarily a bad thing, and may instead reflect shifting priorities: SFPL is now looking to innovations in its programming and public services to transform the way it works with the city community.

“I think that there have been some positive developments that represent things that will be part of our new normal,” said Patterson. Citing programs like virtual book events, outdoor storytimes (opens in new tab) and curbside book pickup (opens in new tab), Patterson and other SFPL staff anticipate that these events will become mainstays as the library adapts to a hybrid world.

Outside of book circulation, SFPL sees the pandemic as an opportunity to really lean into its position as a public institution that connects the city’s residents to a whole range of resources, even if virtual. City-wide literary events (opens in new tab) and interviews with high-profile authors like Chanel Miller (opens in new tab) drew large virtual crowds from as far as Australia, France and Japan. Family Fun Day events (opens in new tab) have allowed librarians to reach out to people in their own neighborhoods, and the library’s 2021 Summer Together initiative (opens in new tab) lined SF kids’ bookshelves with nearly half a million free books.

Yet, library officials say they are especially proud of its investments in more everyday, practical resources that have underscored SFPL’s role as the city’s core community learning hub (opens in new tab).

When California’s unemployment rate spiked (opens in new tab) to a record high of 15.5% in April 2020, for example, the library offered virtual programming surrounding personal finances and career development. These efforts produced new patterns in how San Franciscans started using the library: SFPL’s Jobs and Careers department reported (opens in new tab) a 520% attendance increase in its career programs, and other finance and business classes saw attendance rates grow by over 110%.

“We’re really meeting the community’s needs for programming that’s relevant to them, but also trying to make it as accessible as possible,” said Lambert.

These programs may not translate into increased circulation trends or inflate in-person attendance numbers at SFPL’s branches. But taken together, the new programming efforts, public service work and resumption of in-person branch operations underscore what Lambert and SFPL’s staff hope to do as SF emerges from pandemic turmoil: “We want to reignite that love of reading, that love of learning.”

5. Neighborhood Libraries are Products of Their Patrons

SFPL has over 3 million books in its collection, but only a handful have the honor of being the top circulated titles across all of SFPL’s libraries.

Crying in H Mart and the latest fiction by Irish novelist Sally Rooney rank among the top adult fiction and non-fiction titles read by San Franciscans in 2022, perhaps reflecting the influence of Book TikTok (opens in new tab). SF’s young readers seem to be in a bit of a strange place these days, circulating four installations of the Dog Man series and a graphic novel called Guts more than any other titles.

These rankings look different when viewed branch by branch. Each library caters to a unique neighborhood and set of patrons, and circulation often reflects that fact: the Chinatown branch includes Chinese language titles within its top five most popular genres, while the Western Addition branch (located right below Japantown) shows Japanese non-fiction titles among its most circulated genres.

In an effort to showcase the diversity of SFPL’s branches and patrons, the library launched its Explorer Program last fall, which encouraged residents to visit each of SFPL’s branches.

Check out the map below to see how materials in circulation vary between each neighborhood branch. While the list of top 5 types of materials circulated at each site almost always includes juvenile media (fiction, picture stories, graphic novels), general fiction and DVDs/feature films, our map highlights three “unique” genres that show up within the top 25 materials circulated at a given branch—everything from teen magazines to rock CDs and cookbooks.