As it does most days, the sun rose on March 5, 2021, over a network of Bay Area professionals who work to hide the ill-gotten gains of foreign oligarchs—whether they are aware of it or not.

This time, it was San Francisco businessman Pavel Cherkashin emailing a Menlo Park banker about a shell firm that had been set up as part of a covert financial network whose owner is believed to be a straw man for the secret wealth of Vladimir Putin.

Dmitry Vasyutinskiy, a financial advisor at a Morgan Stanley Silicon Valley office, said U.S. law required him to find out who really owned the shell firm. This was important because international money laundering—of the type practiced by oligarchs, drug lords, corrupt potentates and other shadowy figures—involves creating a twisted path that obscures who really controls the wealth.

After some back and forth, another group of investment managers on the email chain offered Vasyutinskiy a road map. The managers said the ownership traced its way through a series of firms registered in offshore havens, including the Cayman Islands. The trail ended at a trust fund created by a Russian woman named Kuncha Kerimova to purportedly provide for her grandchildren.

That explanation seemed to answer Morgan Stanley’s questions, but it left out a key detail.

Kuncha Kerimova is the mother of a Russian oligarch who has been under U.S. sanctions since 2018 and who received large sums to invest from “the caretaker of Vladimir Putin’s wealth,” according to an EU sanctions document.

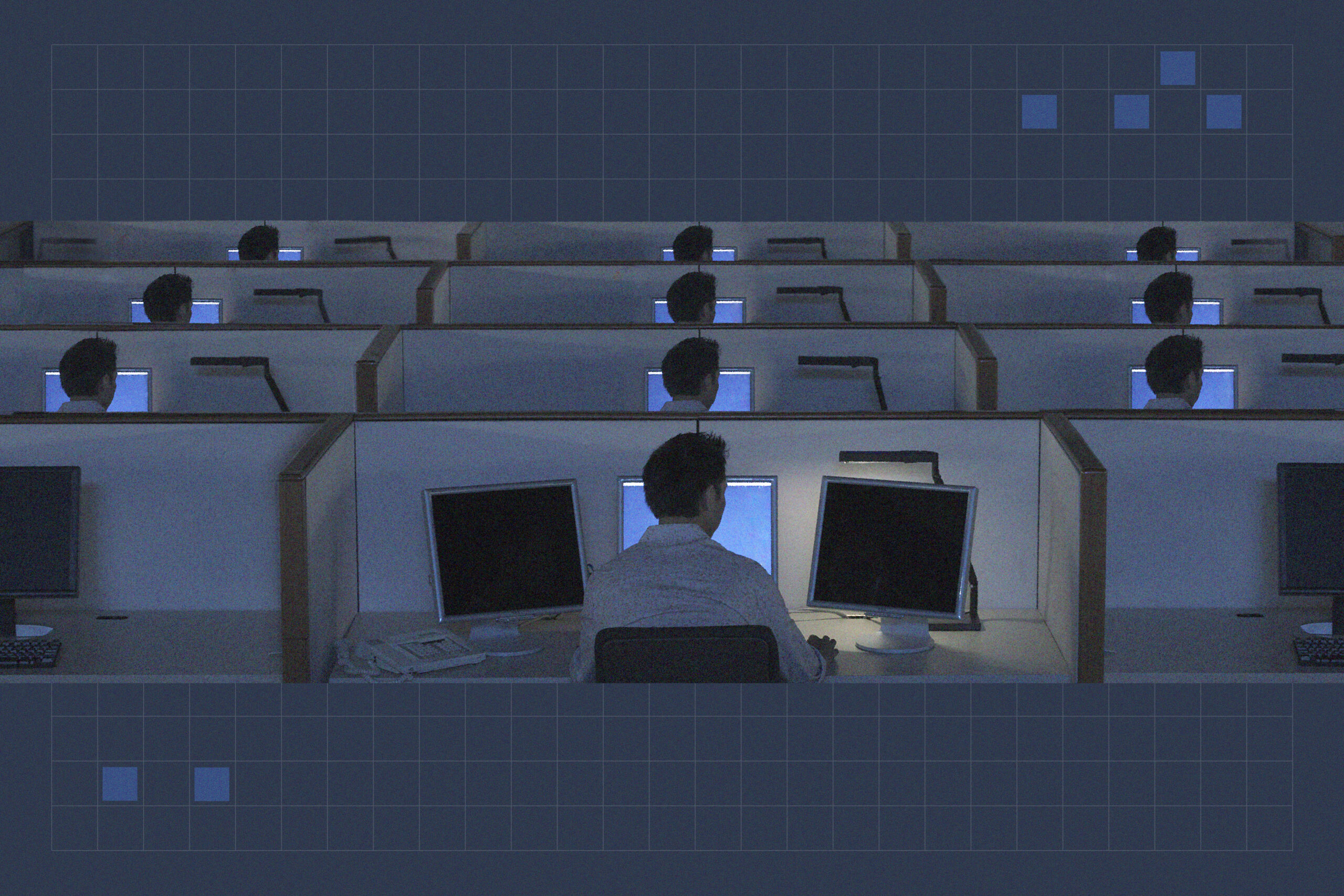

It is this opacity that underpins a cottage industry of financial professionals, some of whom operate in San Francisco and Silicon Valley. Suleyman Kerimov, the oligarch in question, had invested $28 million in the Bay Area, a mere sliver of his estimated $4 billion fortune. But moving that money required the services of more than a dozen lawyers, accountants, investment managers, bankers, agents and other experts, according to thousands of secret business records obtained by The Standard.

A Blind Eye

Most of these people labor under no legal requirement to know whose money they’re handling.

As The Standard reported earlier this month, members of Congress have sought to change that with the Establishing New Authorities for Businesses Laundering and Enabling Risks to Security (Enablers) Act, a measure that National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan says the Biden White House fully supports. The Act would require lawyers, financial consultants, art dealers and others who handle large amounts of foreign assets to figure out the true identities of their clients. But as of now, it appears unlikely to pass before this session of Congress ends.

Europe has also recently moved to tighten money-laundering restrictions. The European Union is expected to place new restrictions on cryptocurrency trading, require greater due diligence for the sale of precious stones and metals, and limit the size of cash transactions through the bloc.

Experts say that illicit finance poses a serious threat to U.S. national security. But its effects can also be felt locally.

Foreign investments in real estate can drive up housing prices and turn habitable condominiums and offices into literal shells. In Kerimov’s case, his $5 million investment in the purchase of a defunct San Francisco church derailed plans to turn the cathedral into an urgently needed homeless shelter, The Standard found in a previous investigation into the oligarch’s Bay Area assets.

But oligarch money also has a corrosive effect on the industries that service it, said Nate Sibley, a research fellow with the Hudson Institute’s Kleptocracy Initiative.

“It provides an incentive for U.S. professionals to kind of turn a blind eye to where that money came from and to start bending the rules,” he said. “And, sooner or later, there are some firms that just end up depending on those sorts of dubious clients.”

The increased availability of such services, in turn, makes the United States an attractive venue for oligarchs and others wanting to secretly move money, he opined. And the growing flow of money provides further incentives for functionaries.

The United States itself becomes complicit in criminal activity, said Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democratic senator from Rhode Island, in an interview with The Standard.

“There is a very dangerous group of international kleptocrats and criminals, and we in the United States are allowing shelter to them for their assets—and in that sense, aiding and abetting their evil behavior,” said Whitehouse, who is a co-sponsor of the Enablers Act.

Vasyutinskiy did not respond to a request for comment. Morgan Stanley declined to comment about its work for the Kerimov-linked firm.

“We take our anti-money laundering and economic sanctions legal and regulatory obligations seriously and have policies, procedures and controls in place to maintain compliance with them,” the company said in a statement.

Kuncha and Suleyman Kerimov could not be reached for comment, but Nariman Gadzhiev, the oligarch’s nephew who worked on his U.S. investments, confirmed in an interview the ownership structure and the oligarch’s mother’s role in it. Cherkashin told The Standard that he followed the law in his work with Kerimov’s investments.

Tangled Web

The Standard reviewed approximately 5,000 pages of records relating to Bay Area investments linked to Kerimov, including emails documenting the exchange between Cherkashin and Vasyutinskiy, the Morgan Stanley banker.

This paperwork included documents produced by a Cayman Islands company specializing in registering shell companies and signed by an attorney in Menlo Park. It included statements from local banks, a contract for a San Francisco accountant, as well as correspondence with a Berlin attorney about how a Cyprus shell company would own part of a San Francisco company.

Even though this and thousands of pages of additional work was ultimately in service of Kerimov—a Putin ally accused by French authorities of laundering money through the purchase of villas—there is no indication participants in this “Oligarch Industrial Complex” were violating the law.

U.S. laws require banks to investigate the provenance of money passing through their accounts, and then report to the U.S. Treasury when they detect something suspicious. But other professionals, such as lawyers, do not have that requirement.

Former FBI agent Debra LaPrevotte recalled a case where she sought to seize some of an oligarch’s assets, which involved meeting with two former agents working for a prestigious law firm the oligarch had contracted. Both agents vouched for their client’s good character.

“What you’re telling me is what he’s told you,” LaPrevotte recalls retorting. “And that’s as far as you were obligated to look into it because your interests are to protect him.”

Although the professionals employed by Kerimov were likely following the law, experts say their work still poses a problem for the United States: Billionaires in countries plagued by corruption and weak rule of law dream of moving their money into U.S. jurisdictions, where it will benefit from the robust American legal system. And so-called enablers, like these service providers, help them do it.

“You know, there isn’t blood on the streets of San Francisco,” Sibley said. “But the money being peddled through San Francisco, through its banks, through its real estate and through its companies, comes from places where there is blood on the streets. And the local professionals are sometimes playing a facilitating role in that.”

In some cases, these professionals specifically set out to work with ultra-high-net-worth individuals from abroad.

Kerimov’s Bay Area investments were connected to a venture capital firm created to connect Silicon Valley startups with investors from Russia and the former Soviet Union, where many billionaires acquired their wealth through questionable privatizations of state assets and have direct connections to the political leadership. Corruption remains a rampant problem across the region.

Leonard Grayver, a California venture capital attorney who is involved in some of the Kerimov-linked transactions, specializes in post-Soviet investors. He told The Standard that he has worked on investments involving half the billionaires in Russia.

Asked whether he had hesitations about accepting fees from oligarchs, Grayver said he did, but didn’t see other options.

“What I’ve learned in 25 years of doing venture capital work: The absence of money is worse than bad money,” he told The Standard.

Not all the professionals were so specialized. Others were simply large, multinational financial service providers or local “mom-and-pop” shops that don’t look too closely.

In Kerimov’s case, those services were important at every stage of the ownership structure. Citigroup set up trusts identified by the U.S. Treasury in November as part of the Russian oligarch’s financial network. Providing advice for the transactions were layers of lawyers, including a former intelligence advisor to President George W. Bush named James C. Langdon Jr., who oversaw the trust fund agreement controlling Kerimov-linked assets in the United States.

Langdon, in turn, requested the advice from Quinn Emanuel, a law firm headquartered in Los Angeles, which told The Standard it had stopped doing business related to a Kerimov-linked trust in 2020.

“We can say, however, that (as with all of our work for clients) it fully complied with the law,” the law firm added in a statement.

Citigroup declined to comment on the services it provided to the Kerimov trusts. In a message, a spokesperson told The Standard: “Citi is committed to conducting all business with the highest consideration for compliance with all applicable U.S. laws and regulations to assist in protecting the financial system from abuse.”

Langdon did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Cherkashin also used the services of Dmitry Kustov, a Russian-born accountant based in San Francisco, for the special-purpose companies holding Kerimov’s investments. When The Standard reached him by phone, Kustov said he did not know about Suleyman Kerimov, but declined to comment further.

“Even if I knew what I [was] doing, I would not have told you,” he said.

The above list is far from exhaustive, but it emphasizes the depth of the problem. Few of these professionals were required to uncover the ultimate beneficial owners of the companies they worked for or the source of their funds.

As a result, some likely did not know about Kerimov’s involvement. Others may simply have chosen to close their eyes.

Only a few were definitely aware: Cherkashin knew that the money came from Kerimov, something that was not illegal when he began his involvement in investing the oligarch’s funds in the Bay Area.

Luminar Technologies, a self-driving car company that launched with the help of $20 million of Kerimov’s wealth, actually did know whom they were dealing with, according to Gadzhiev, the oligarch’s nephew and money manager. He said Luminar’s founder Austin Russell met personally with Kerimov, and those meeting plans were corroborated by emails reviewed by The Standard.

Russell and representatives from Luminar did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Congress Takes Notice

The fact that so many U.S.-based service providers could work on a sanctioned oligarch’s investments without knowing or caring was always a problem.

But the issue has grown more urgent for policymakers in recent months. In February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, demolishing cities and massacring civilians in the regions it occupied. The U.S. and countries of the European Union rushed to provide Ukraine with millions of dollars in aid.

The conflict drove home the degree to which oligarchs, who benefit from and also buttress the authoritarian political system of Vladimir Putin, may indirectly threaten not only the security of Russia’s neighbors, but also of the West and its allies.

That has brought oligarchs and their money under greater scrutiny. In the nine months since the invasion, the United States has rapidly expanded its sanctions against politically connected Russian individuals and companies.

In June, the U.S. Treasury blocked Hertiage Trust—which held Kerimov’s U.S. assets—under the 2018 sanctions against the oligarch, stating that he has “property interest” in the Delaware entity. The agency said that the trust holds assets worth over $1 billion. Kerimov’s Bay Area investments—particularly the Luminar shares, which have markedly appreciated in value since 2016—are now frozen.

In November, the Treasury also imposed sanctions on what it called “a broad network of Kerimov’s family members, associates and facilitators.”

But the most important move aimed at foreign oligarchs, alleged kleptocrats and money launderers actually got its start before the war: the Enablers Act.

Introduced by Rep. Tom Malinowski (D-New Jersey) in October 2021, the bipartisan bill would require investment advisors, art dealers, certain lawyers and accountants, trust and company service providers, and others to adopt anti-money laundering procedures and help better safeguard the U.S. financial system.

A version of the bill was included in the National Defense Authorization Act for 2023. In July, it was approved as part of that bill in the House of Representatives. But, earlier this month, it was excluded from the Senate text of the authorization act, likely sidelining its passage for now.

In practice, the Enablers Act would make it harder for investors to hide their identity behind an offshore company, shell company or trust. Currently, that is often enough to hide the true owner.

“If an [investor’s] agent says, ‘Hey, I’m representing a company registered in Dubai,’ then all they have to do is check that the company is not on some sanctions list, but they don’t have to ask [about] the source of funds,” said Gary Kalman, executive director of the U.S. operations of Transparency International, a Berlin-based anti-corruption group.

If passed, the act would be a new step in efforts to impose vigilance on industries that can serve as conduits of money laundering and financial crime.

It would make it easier for the authorities to prevent and investigate those crimes, according to former FBI agent LaPrevotte.

“It puts the onus on the people who are managing the money to know the source of the money,” she told The Standard.

The Enablers Act would bring the anti-money laundering requirements for these professionals close to those that exist for banks.

But the sweep of the bill has earned it some pushback. In October, the American Bar Association came out against the Enablers Act, alleging that it could require lawyers to “report attorney-client privileged and other protected client information to the government.”

Sen. Whitehouse, who sponsored the bill in the Senate, believes that, sooner or later, it will pass.

“It is a national security matter for the United States to have to deal with the corruption and the criminality that occurs overseas,” he said in an interview with The Standard.

He believes that corruption in Russia allows Putin to wage war in Ukraine, while illicit finance helps narcotics cartels to profit off selling drugs that kill Americans. For this reason, American financial managers and service providers shouldn’t be able to turn a blind eye to who is behind the money.

“It’s a bit like trading with the enemy in war time,” he said.