In March, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a massive project: transforming San Quentin Prison, a maximum-security penitentiary with the largest death row in the U.S., into a rehabilitation and education facility—in just two years.

Constructed in 1852, San Quentin is California’s oldest prison. Can it also be a model for a more progressive vision of criminal justice?

That question loomed over the governor’s recent naming of several new prison council advisors. The appointments read like a local who’s who of the prison reform movement: Kenyatta Leal, executive director of the Next Chapter project (opens in new tab); Mimi Silbert, president and CEO of Delancey Street (opens in new tab); Chris Redlitz, executive director of The Last Mile (opens in new tab); Michael Romano, founder of the Three Strikes Project (opens in new tab); Jody Lewen, the president of Mount Tamalpais College (opens in new tab), and others.

San Quentin has an infamous reputation due, in part, to its death row and to the notorious criminals, like Charles Manson, who were once incarcerated there—yet, the institution is arguably already the most progressive prison in the state.

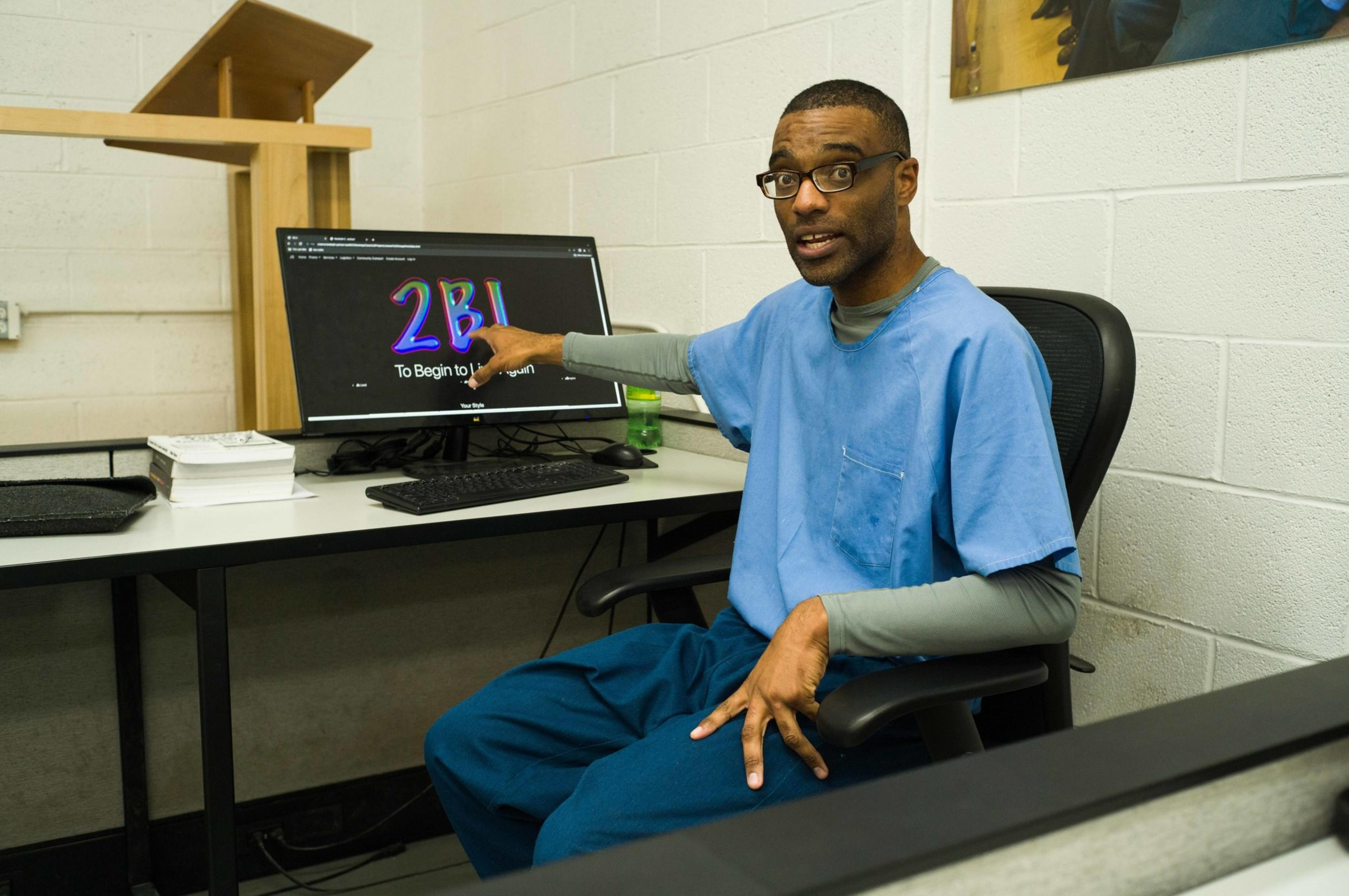

It offers a bevy of rehabilitation programs, everything from computer-coding classes and college courses to gardening and yoga. The facility has so many programs, in fact, that prisoners will request transfers to San Quentin to take advantage of them. The prison draws from a deep bench of Bay Area do-goodery. The same cannot be said for a remote state prison like Pelican Bay in Crescent City or High Desert in Susanville, where it can be difficult to staff positions for basic community needs, let alone find volunteers willing to spend their free time teaching men and women behind bars.

In addition, San Quentin dismantled its execution chamber (opens in new tab) in 2019—a move that was echoed by Newsom’s announcement four years later that he planned to shut down death rows across the state (opens in new tab). No one has been killed by the state of California since Clarence Ray Allen (opens in new tab) was executed at San Quentin 17 years ago, despite the state having the largest death row in the country.

Given San Quentin’s already extensive history of leadership and reform—as well as the fact that there are 34 other state prisons (opens in new tab) in California with much higher needs—why did Newsom choose to start with San Quentin?

“This is building a scalable model that can be deployed to other facilities,” said Izzy Gardon, deputy director of communications for the Governor’s Office. “So it makes sense to go to one of the current leaders.”

The governor aims to remake the prison by 2025 into a “one-of-a-kind rehabilitation center focused on improving public safety through rehabilitation and education via a scalable ‘California Model.’”

Newsom knows that the target will be difficult to hit. “We were talking about the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches in here,” Newsom said during the press conference in San Quentin announcing the project, “and just changing the jelly probably took 10 years.”

The condemned row housing unit and a Prison Industry Authority Warehouse are to be transformed into a “center of innovation” focused on education and rehabilitation.

Other aspects of the transformation could be more underwhelming. While the prison is in the process of being officially renamed the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center, it is already part of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Prisons often employ euphemistic language, like “administrative segregation” for solitary confinement, demonstrating that language does not always signal what it intends.

It is also unclear if the $20 million set aside for the project will be enough—or if that money will evaporate in the state’s ongoing budget crisis (opens in new tab).

With everything that’s at stake in terms of California’s massive prison system—what one author and scholar has called (opens in new tab) the “Golden Gulag”—it’s worth any attempt at reform.

“San Quentin is great compared to other places, but there’s still a ton of work that needs to be done,” Lewen said.