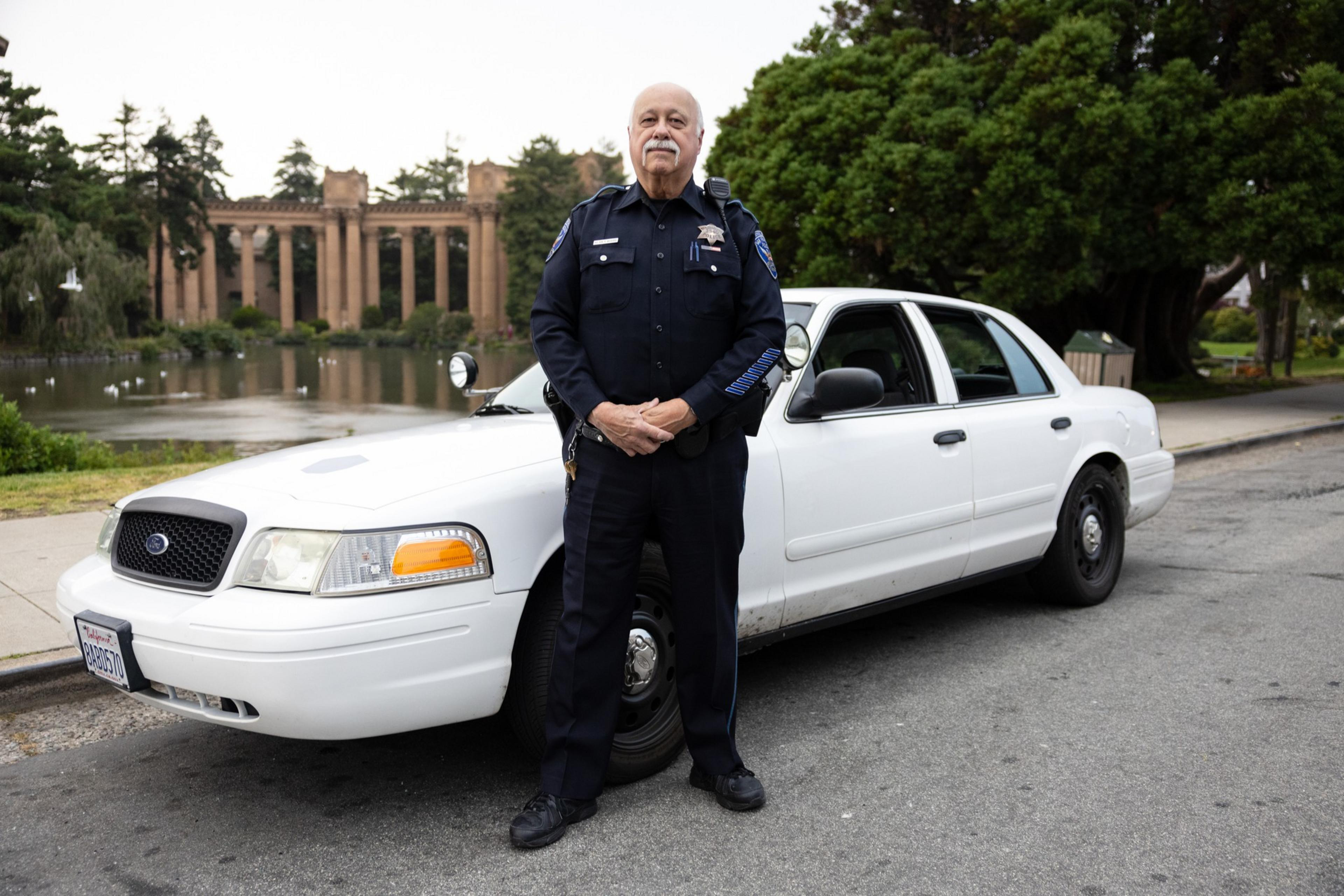

Alan Byard starts his shift by scribbling his name on a sign-in sheet at the police station in San Francisco’s Fillmore District. After a briefing on the area’s crimes, he starts his unmarked Crown Victoria and radios to dispatch that he is on duty.

Byard wears a dark blue uniform like any police officer, except for the light blue stripe down his pants. A city seal is sewn into its shoulder, and he wears a six-point star on his chest and carries a gun. But he’s not a police officer. The 68-year-old is not a security guard, either. Byard is what’s known as a “patrol special.”

Patrol specials operate in a realm between San Francisco police and for-hire private security. Private businesses and residents pay for their services, but unlike private security guards, which are overseen by a state agency, patrol specials are licensed by the city. They have a much closer and more official relationship with the San Francisco Police Department, and the city gives them the right to patrol the streets in designated areas, referred to as beats. However, that’s a privilege they must pay for.

Byard currently patrols three beats in the Marina District and has 190 paying customers—local merchants and residents looking to secure their property. He charges $65 a month for providing security for a residence, and the service for businesses starts at $300 a month. That can include check-ins on a home when someone has gone on vacation or daily looks at a business after hours.

When Byard started what would become his five decades-plus patrol special career in 1970, he was one of 450 patrolling the city. Today, he is the last patrol special on duty—and he plans to retire soon.

With property crime and public safety concerns on the rise amid what police characterize as a severe staffing crisis in their ranks—and increased local scrutiny of the private security industry after one of the roughly 10,000 guards working in San Francisco fatally shot an unarmed man—some city leaders are floating the idea of bringing back the patrol special program.

“Given the ongoing police staffing crisis, public safety must be an all-hands-on-deck effort,” Supervisor Catherine Stefani, who represents part of the district Byard patrols, told The Standard. “District 2 has one of San Francisco’s last remaining patrol specials, but administrative hurdles have hampered its effectiveness and slowed recruiting.”

Discussions around bringing back the program have been ongoing for years, but the idea is gaining momentum following a number of recent events involving security guards, including a 2022 break-in at the Tenderloin’s Black Cat jazz club (opens in new tab) that left the business open to hours of looting after police came and left; an incident that same year in the Castro District involved security guards allegedly racially profiling the public; and the killing of Banko Brown this year in an altercation over stolen candy at a Walgreens.

Brown’s killing is the latest high-profile incident to spark public outcry and calls by city lawmakers to transform the private security guard industry, which some say is too lightly regulated by the state. It also served as a reminder that while the city passed a law in 1972 (opens in new tab) giving SFPD the power to regulate security guards, the department never exercised it. (That law, known as Article 25, is expected to be reviewed this fall, according to Police Commissioner Kevin Benedicto.)

Proponents of the expansion of the patrol special ranks, including Supervisors Aaron Peskin and Stefani, argue that incidents like these would have ended differently if the “specials,” as they call themselves, had been on duty.

Byard, for his part, said that he would have used a less-lethal weapon to stop Brown and, in the case of the Black Cat, would have stayed at the scene and made sure the business was secured.

“There’s a real interest in using it as a tool to help coordinate with the private sector security,” said Police Commissioner Debra Walker, who has been tasked by the commission’s president, Cindy Elias, with putting together a plan to revive the program. “There’s a way of inserting more oversight, more cooperation with the department […] and more rules that they have to follow.”

Walker said the planning will be a joint effort between the commission, police, the police union and the business community. A concrete plan could be presented to the commission for approval this fall, she said.

“We need more blue on the sidewalks, and I don’t think there’s anyone disagreeing with that. This is one way of doing it. We are looking at reimagining it,” said Randall Scott, the head of the Fisherman’s Wharf Community Benefit District, who said he was working with the San Francisco Police Officers Association and SFPD on the issue.

When asked for comment on what role patrol specials might play in San Francisco’s future, and what role SFPD had in the planning, spokesperson Evan Sernoffsky would only say that the department was in discussions with the Police Commission.

How Patrol Specials Work

The Police Commission licenses patrol specials after they pass background checks and undergo 64 hours of required training at the police academy, which includes courses on firearms and criminal law. Each year, they are required to attend refresher courses on firearm use. They are allowed to carry a gun and to communicate with police dispatch. Any disciplinary actions are overseen by the commission, too.

In contrast, California only requires security guards to complete a 32-hour course on the laws around arresting and protecting people and property, and guards must attend an annual eight-hour refresher course. Security guards are also required to get a special license to carry a gun.

One of the major differences between private security and patrol specials, aside from the city oversight, is that they are legally allowed to patrol the streets, whereas security guards technically are not allowed to do so—they are supposed to stick to private property. Patrol specials are also given access to police radios and dispatch and can even be sent to a call by police.

Each individual patrol special is allowed three beats, and they negotiate privately with businesses and homeowners in the area to provide services.

Walker, of the Police Commission, said the newly imagined patrol special program would involve modernizing and beefing up what currently exists. Patrol specials might be required to undergo additional training, report far more data about what they do and perhaps wear body cameras, Walker said. Neither she nor others The Standard spoke to were able to provide details about the enhanced training and reporting under consideration.

While patrol specials would not replace police, Walker said, they could do much of the community policing that an understaffed police department doesn’t have time for. That could include liaising with city departments for health or homelessness issues, for example.

Scott of the Fisherman’s Wharf Community Benefit District said the majority of the 14 members of the San Francisco Benefit District Alliance, of which he is president, supports the plan. He speculated the rollout might start with expanded patrol specials in a few districts like Fisherman’s Wharf and the Castro as a sort of pilot program. The staffing, he said, could come from security guards already working for a benefit district who could become patrol specials. Scott also said he has spoken with former police officers who have expressed interest.

Supervisor Stefani said she is pushing for more expediency in getting background checks done on potential patrol specials so they are ready to hit the streets.

But not everyone is enthusiastic about the plan.

Ken Lomba, who heads the San Francisco Deputy Sheriffs’ Association, said he thinks the city should prioritize using more deputies on the streets before it expands or reimagines patrol specials.

“It’s a good idea for deputy sheriffs to do,” Lomba said. “But it’s a bad idea for non-law enforcement to do police special work.”

Others think more uniformed officers with guns—whether they are cops or not—is a move in the wrong direction.

Anti Police-Terror Project Deputy Director James Burch said he is concerned about the plan because it would put more people on the streets with less accountability and transparency than police. He worries that the plan would lead to “more of the same” kind of events like Brown’s death.

Mayor London Breed’s office did not respond to a request for comment on her view of expanding the patrol specials program.

A Gold Rush-Era Origin Story

Patrol specials have a long, storied history—they were created when the city had no police department. There is even a square in the Castro—Jane Warner Plaza (opens in new tab)—named for a much beloved special. And a 1992 film called (opens in new tab)Kuffs (opens in new tab), starring Christian Slater as a patrol special, put the San Francisco institution on the silver screen.

Patrol specials date back to the Gold Rush era and were organized to provide protection for merchants and citizens when the city was lawless, wrote the city controller in 2010.

In 1935, the city wrote the existence of patrol specials into the city charter. The current rules and regulations governed by the commission were set up in the 1970s when hundreds of patrol specials still walked the streets.

In 1982, the city was divided into 64 beats patrolled by specials who purchased beats for as little as $500.

By 2010, there were just 26 active beats.

For now, there is just one.

Patrol specials don’t have an unblemished history.

In 1996, a patrol special in the Castro named Alan Stancombe was charged with felony assault and battery in connection to an arrest in 1994 of a pickpocket outside of a bar.

As recently as 2010, a controller’s report noted that the patrol special program was a liability to the city and recommended it be disbanded.

This history, along with competition linked to lucrative overtime gigs for off-duty police (opens in new tab), has led some in positions of power to call for the elimination of patrol specials—until recently.

Peskin said he would be open to a reimagined program, but given the police department’s history of relegating patrol specials to “second-class” law enforcement status, the supervisor said he’s not expecting smooth sailing for an expanded program.

Over the years, the police have tried to end the existence of patrol specials, Byard said.

“Now you have a lot of citizens who see what patrol specials are,” he said. “The word got out, ‘Here’s a program that costs the city next to nothing […] why not get extra police officers basically for free?’”