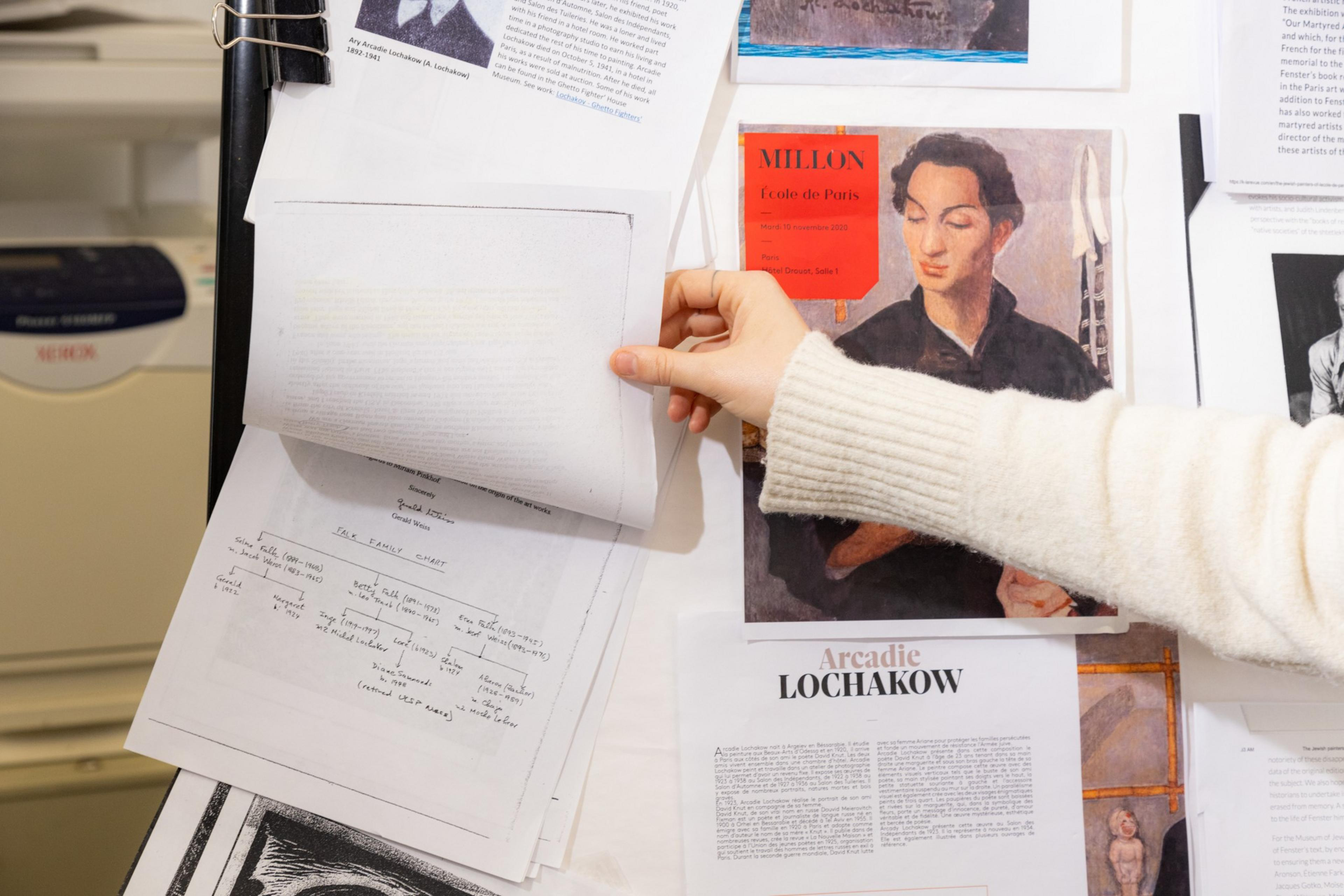

The Standard received an outpouring of messages in response to our recent story about Ary Arcadie Lochakov, the Holocaust victim whose lost artworks were discovered on a park bench in San Francisco 81 years after his death. Readers have weighed in with their theories, questions and suggestions—and now it’s time for some answers.

In case you’re just catching up, 38 works of art made by Lochakov, an artist who was born in the Russian Empire and died in Nazi-occupied Paris in 1941, were discovered by Port of San Francisco workers in Crane Cove Park in May 2022. The pieces had been carefully arranged on a cement bench in the park without any clue to their past ownership.

Through some careful sleuthing, the port employees uncovered the name of the artist and some basic facts about his life. However, even after determining the art’s legitimacy and committing to transfer the works to the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris, large questions remain: How did the artworks resurface in San Francisco so long after their disappearance? And who abandoned them in the park?

Before we get to those answers, The Standard can now reveal more details about the artist Lochakov’s life, some of which come courtesy of the book Our Martyred Artists by Hersh Fenster, originally published in Yiddish and recently translated into French. Fenster, a mid-century journalist and author, profiled 84 Jewish artists working in the creative and religious haven of prewar Paris. His book doesn’t simply include biographies of the artists, but also recollections from friends, informal anecdotes and critical reviews.

From the two pages devoted to Lochakov, we learn that the artist arrived in Paris in 1920 with his best friend David Knout, who later became a fighter in the French resistance during World War II. Lochakov’s artworks were displayed in prestigious exhibitions in Paris—the Haussmann galleries, the Salon d’Automne and the Salon de Tuileries—and as far away as Chicago.

Fenster describes Lochakov as a serious, principled man who preferred solitude to being with others. He didn’t smoke or drink. He ate little and spoke little, too. “The only thing that remains is the memory of an honest man and artist, pure like crystal,” wrote the author.

Publishing his book in 1951, Fenster had no idea that 71 years later a trove of works by Lochakov would appear more than 5,000 miles from the city where he lived, made art and later died of malnutrition during the Nazi occupation. Yet the artist’s ghost, it seems, refuses to disappear.

Here are some of the questions asked by Standard readers—and the new information we’ve learned since publication.

The port employees discovered 48 artworks, but only 38 were signed by Lochakov. What’s the deal with the other 10?

While port representatives originally claimed the 10 unsigned artworks—which appear to be more recent—were not traveling along with Lochakov’s pieces to Paris, Port Commission’s spokesperson Eric Young has since said that all 48 artworks will be going to the Museum of Jewish Art and History for research and study.

Will Lochakov’s works be on public display in San Francisco before they move to Paris?

The port plans to display Lochakov’s artworks locally before they make their journey to Paris, but it has not yet determined a time or place. “We’re having a series of internal communications,” Young said.

How could there be no surveillance video of Crane Cove Park revealing who left the artworks behind?

With cameras seemingly everywhere across the city, some readers wondered how it was possible there wasn’t any surveillance video—and why they hadn’t heard about the port’s mysterious art discovery sooner. “The port was letting people know,” Young said. “We were doing research, contacting experts and preparing for a smooth process to transfer the artworks.” Yet if a paper trail had not been created when the Port Commission passed a resolution to transfer the works to Paris, The Standard likely would not have heard about this story. While the port does not operate any surveillance cameras at Crane Cove Park, that doesn’t rule out the possibility that there could be video available from another source.

Why aren’t the works staying in San Francisco?

Numerous readers wondered why the works wouldn’t stay here, perhaps going to the Contemporary Jewish Museum or another local art museum. While port staff reached out to various San Francisco and Bay Area fine arts and cultural institutions during its research, Young said, they were not able to accept the works into their collections. The Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris, which already has an exhibition on the so-called “Lost Shtetl of Montparnasse,” has been actively seeking the work of the martyred artists and was determined to be the best home for the artworks.

Multiple works were framed by a single store in Huntsville, Alabama. Is that store still around?

Many readers asked for more details about the framing store that provided a potential clue to the pathway that the artworks took from France to the U.S. The Campbell Wall Paper Store in Huntsville, Alabama, is where numerous of the found artworks were framed. Yet that store—once located in a charming historic building—is long gone, and has been replaced by the Fountain, Parker, Harbarger & Associates insurance company, which happens to be across the street from another historic structure, the Times Building, which houses the daily newspaper in Huntsville.

What’s the connection to Huntsville anyway?

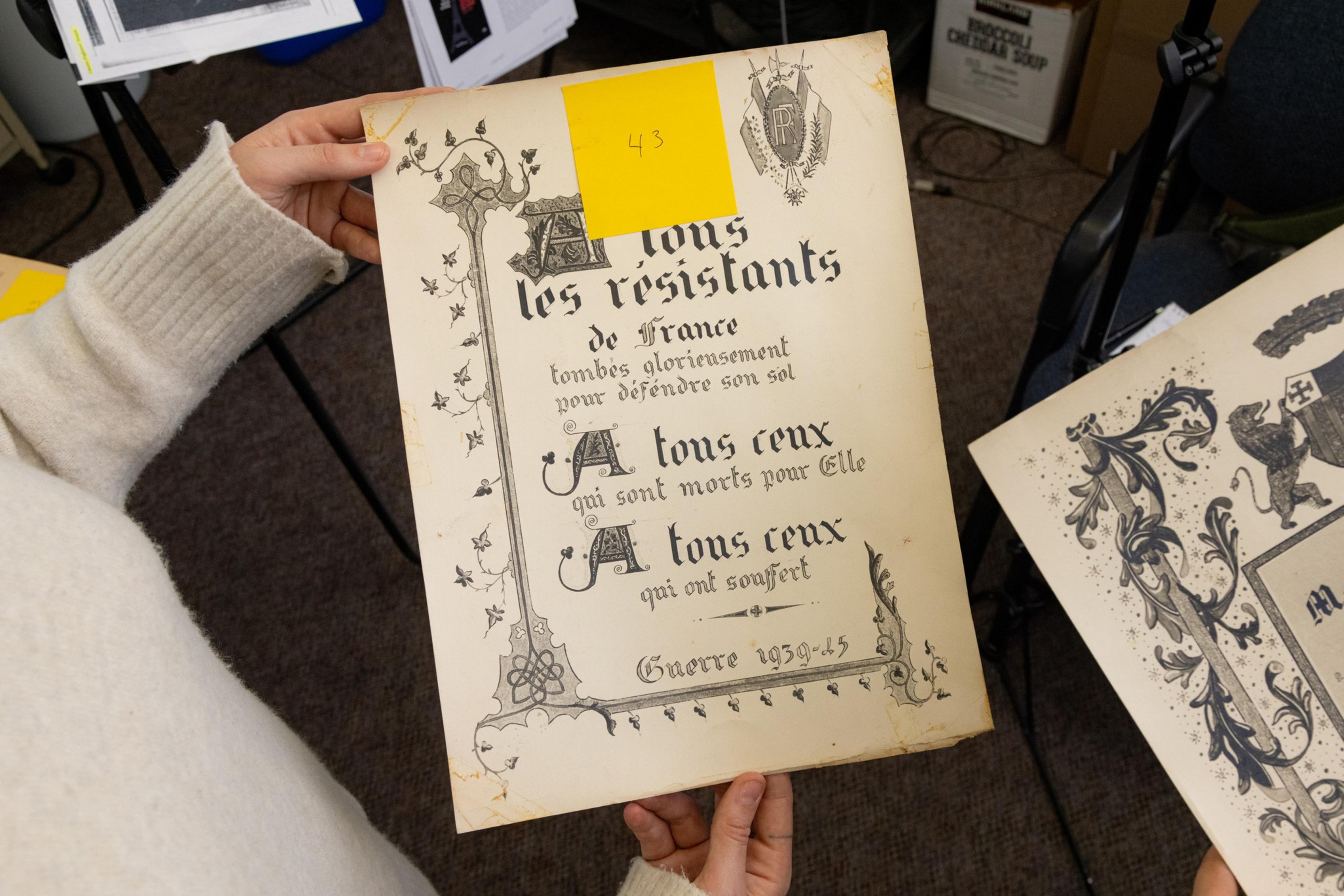

Multiple readers posited a theory that the Huntsville connection could go beyond a simple framing store. The Alabama city was once the home base of a top-secret American program (opens in new tab) called “Operation Paperclip” that brought some 1,600 Nazi-trained rocket scientists to the U.S., headed by the engineer and former Nazi party member Wernher von Braun. However, there is no indication of a Nazi connection to the lost artworks. Rather, the chain of custody appears to have gone through members of Lochakov’s family.

How does that get us to San Francisco?

We’re saving the best for last—an update on how the Lochakov trail leads to San Francisco. A 1997 letter held by the Jewish Ghetto Fighters’ House in Israel details how the museum came to acquire some of Lochakov’s prints, and in that letter, there is a family tree that includes Ary Lochakov’s nephew, Michael Lochakov.

Michael married Inge Traub in 1946, and the couple joined Traub’s parents in New York City, later moving to Providence, Rhode Island, where they were divorced in the 1950s. Traub ultimately remarried and moved with her new husband to—wait for it—Huntsville, Alabama. Inge’s sister Lore Traub also moved to Huntsville and had a daughter, Diane Sammons, in 1948.

Sammons, in turn, moved to San Francisco and lived there for at least 20 years. “The paintings in question belonged to [her aunt Inge Traub],” said John Magri, the former longtime partner of Sammons, who lived with her in San Francisco for 20 years before they split up in 2016. Magri traveled yearly with Sammons to Huntsville to visit her family and remembers seeing Lochakov’s prints hanging on the walls of the family home. Sammons, a former UCSF nurse, died in 2019; Magri now lives in San Rafael.

Magri also remembers the stories Sammons’ mother, Lore Traub, told about surviving Kristallnacht as a teenage girl and eventually escaping to New York via Holland. According to Magri, Sammons’ aunt Inge received a medal from Charles de Gaulle for her role in the Resistance and suffered from manic depression that often left her bedridden.

As for the artworks themselves, Magri was surprised to learn they had turned up on a park bench in San Francisco. He guessed they had passed along to Sammons when her mother died in 2011, but he believes Sammons never would have wanted them to end up abandoned. Sammons was the caretaker for her mother, who had all the art and “loads of papers,” Magri said.

“She was kind-hearted,” he said. “She loved the arts.”

That leaves one key question remaining: How did the artworks, likely part of Diane Sammons’ estate, end up on a park bench after her death? Her last living kin, according to Magri, is a half-brother in Florida, but the trails to him have so far run cold.

Maybe you, reader, know something we don’t? We can’t help but think there’s yet more of this story to unravel.