Judy Hamaguchi can whip up images of 1950s Japantown like it was yesterday.

The 75-year-old recalls the neighborhood as a small, self-contained world. Everything was at your fingertips: a doctor, dentist, shoe repairman, liquor store or hotel was right around the corner, all surrounded by eclectic San Francisco Victorians.

But like the fog that can roll in and quickly change the entire tenor of the city, a redevelopment project suddenly transformed Hamaguchi’s life.

In the name of urban renewal, San Francisco razed hundreds of businesses and displaced tens of thousands of residents, including Japanese Americans, Black people and a small community of Jews—considered one of the darkest blotches on the city’s history.

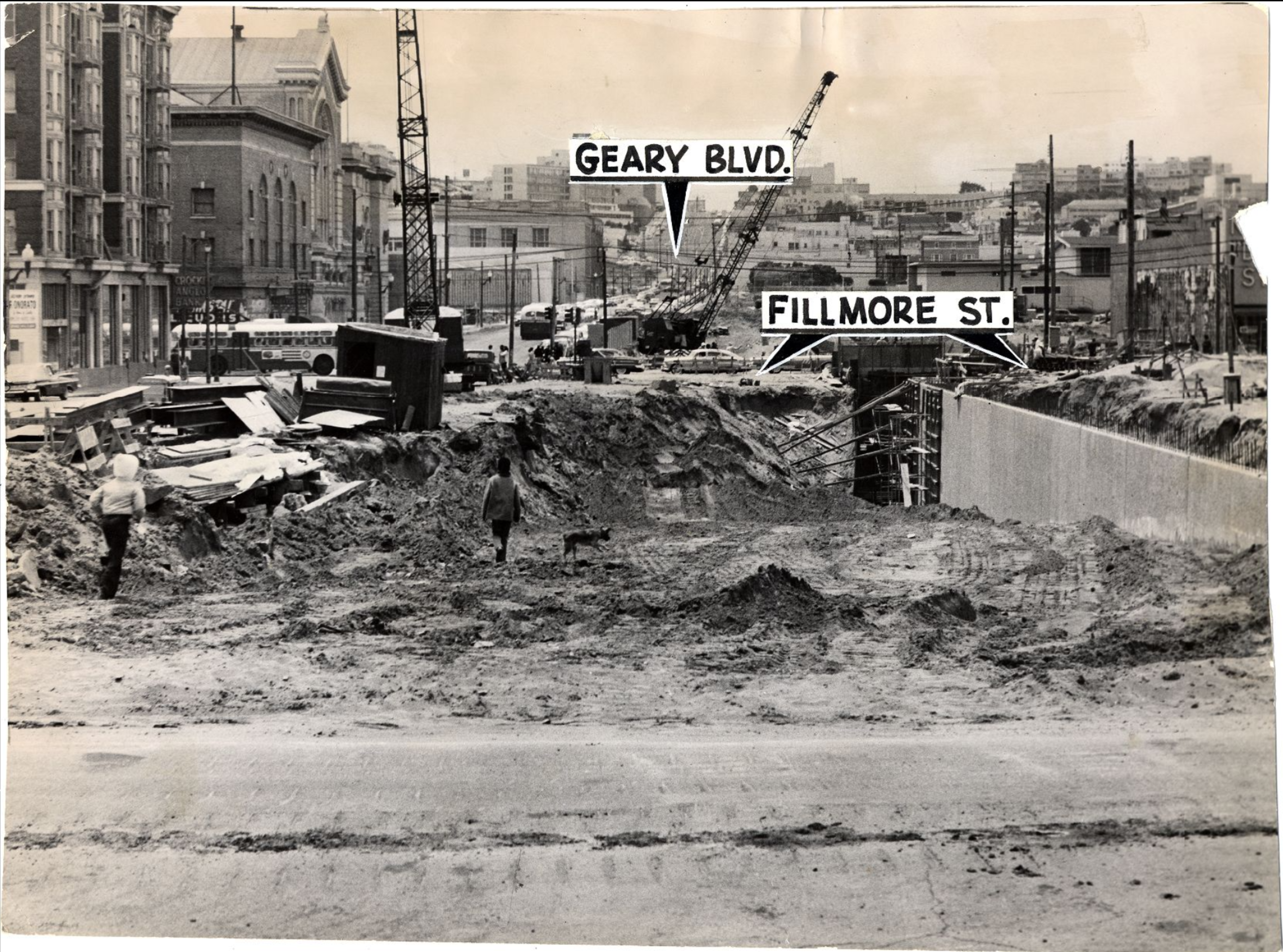

At the center of the demolitions was a road widening project in the early 1960s that encompassed a stretch along Geary Boulevard from Divisadero Street east to Laguna Street, where 28 blocks were leveled.

The total sum of the destruction was breathtaking: 883 businesses, up to 30,000 San Franciscans displaced and around 2,500 Victorian homes wrecked, according to the California Migration Museum (opens in new tab).

Envisioned during a time when the car was king, the widening of Geary Boulevard cut a scar between Japantown and the Fillmore neighborhood, physically separating the communities to this day.

The story isn’t new to those steeped in the city’s history. But now residents are seeking to heal decades-old wounds. The city is currently exploring how to transform the car-heavy corridor to bring housing, shops or some sort of green space.

This month, San Francisco received $2 million through a federal grant program (opens in new tab) aimed at trying to rebuild infrastructure that uprooted families and business owners decades ago. Supported by Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi, the grants (opens in new tab) will allow the city to begin exploring options for transforming the expressway and studying the wider surrounding neighborhoods for improvements.

“I don’t know what needs to come down for something else to come up,” said Hamaguchi, who now lives in the Richmond District. “But we know that it is important to bring families back into this community.”

‘A lot of dirt and dust’

The rise of modern-day Japantown came after the 1906 earthquake devastated the city, destroying the community’s previous home in the South of Market neighborhood and forcing residents and businesses to relocate west.

Just to the south, the Black population of the Fillmore District surged in the 1940s. At one point, the city boasted over 70,000 Black residents, many of whom patronized bustling businesses and jazz clubs in the neighborhood, earning it the title “Harlem of the West.” Both communities had ended up there due to exclusionary housing policies that limited where Black and Asian San Franciscans could reside.

Then a ticking time bomb started. In 1948, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency was established (opens in new tab) and the group knocked down its first home in 1953. Then the Geary Expressway project began, with the city trying to get suburban commuters living in the city’s Richmond District across the city into downtown—by whatever means necessary.

Hamaguchi saw it all while living on the corner of Post and Buchanan streets, a time she describes as traumatic and difficult to talk about. She remembers seeing “a lot of bulldozers, cranes and wrecking balls … and a lot of dust and dirt.”

She specifically remembers the widening of Geary, which was transformed into a submerged, multi-lane expressway that remains a vast canyon of noisy cars to this day with limited walkability.

“I think it had a serious impact,” said Hamaguchi, whose family was eventually pushed out of Japantown in the ’70s. “Things shifted in a way that the neighborhoods interacted.”

Things were no better for the Black community just blocks away. Majeid Crawford, who heads a local nonprofit, said family members told him of a time when the area was filled “wall to wall” with businesses and beautiful homes with shops on the bottom and families living on top.

Then the bulldozers came. “They literally destroyed the community overnight,” said Crawford. The changes, he said, diminished Black economic power in the city and contributed to the dwindling of the city’s African American population over the years.

“This was a bad planning decision and part of racist redevelopment to basically create a freeway through these neighborhoods,” said Supervisor Dean Preston, who helped land the $2 million grant. “It’s a very wide stretch that is exclusively focused on high-speed traffic.”

What will Geary become?

Preston said the ideas for what could come of Geary are still in the very nascent stage. One source of inspiration is other areas that once had freeways barreling through them, like parts of Hayes Valley.

One big distinction, however, is that Preston wants to keep the area affordable, which isn’t what happened in Hayes Valley. Nonprofit leader Crawford says the effort to rebuild the ties between the neighborhoods remains difficult since the people who used to interact long ago are now gone.

“We should design the housing so it benefits the communities that have been harmed,” he said. “[For] a young family in Antioch because that’s the only place they can live. For all the young people who’ve been scattered across California. Let’s make the housing about them.”

Emily Murase, executive director of the Japantown Task Force, said she would prefer a tunnel-top park like the one that opened in the Presidio in 2022, or housing, or a town square. She said the federal grant will allow community members to convene this fall to start brainstorming ideas for Geary’s makeover.

“I am interested in a range of options,” said Murase. “Geary doesn’t have to be six lanes.”