Broken windows. Radioactive waste. No heat or running water. These don’t sound like the ingredients for a creative haven, yet they are exactly what hundreds of artists have endured (opens in new tab) at the Hunters Point Shipyard for the past four decades.

“It’s quiet, and it’s spacious, and it’s cheap,” said Robin Denevan of the post-industrial spread perched on San Francisco’s southeastern waterfront. Inspired by waves, Denevan works with caustic and enamel to make durable artworks of shoreline and horizon.

With more than 200 artists working in nearly every medium—from painting to plasterwork, garment making to photography—the almost 500-acre shipyard constitutes one of the country’s largest creative communities.

“It’s an island of artists in San Francisco,” said Barbara Ockel, the president and CEO of the Shipyard Trust for the Arts (opens in new tab). “It really feels like a community, and they feel privileged to be here.”

To celebrate the last 40 years of their unlikely existence, participating artists inhabiting these oversized warehouses will throw open their doors this weekend to the public with tours, two food courts, a beer garden and live jazz. (Admission is free and includes free parking with RSVP (opens in new tab).)

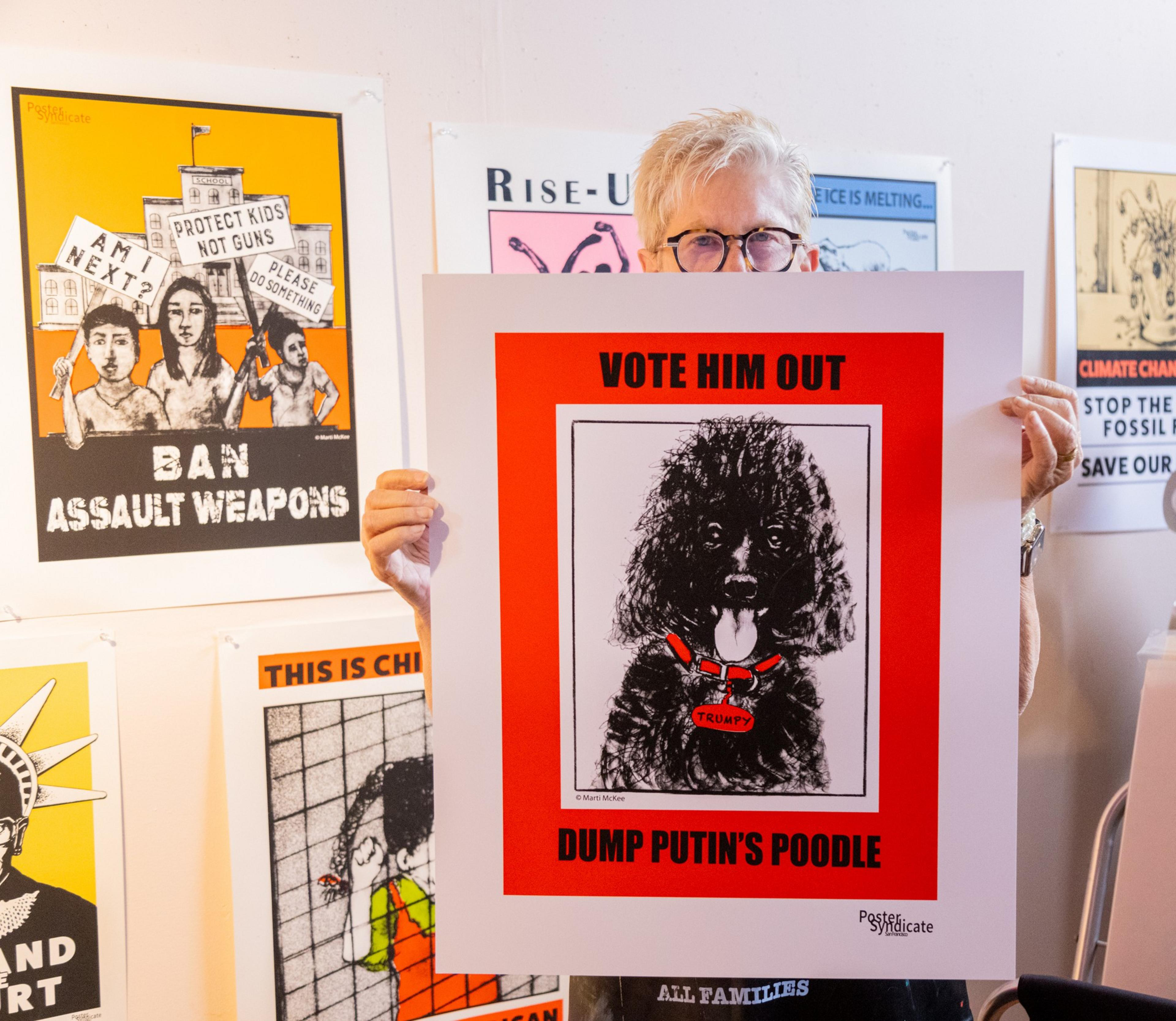

Attendees will have the opportunity to snake their way through dozens of open studios, meet artists and participate in activities like pulling their own prints with Marti McKee, who makes posters for marches and demonstrations.

The artists have taken up shop in a too-often forgotten southeast corner of the city, one with a thriving Black community and a storied—and troubling—past. The U.S. Navy, who bought the shipyard in 1941 and assembled the atomic bomb it dropped on Hiroshima there, left the site littered with radioactive waste.

“No one knew the consequences of it,” Ockel said.

Soil samples are still being tested today, and air monitors were installed just a few months ago. Yet Ockel said none of the recent radiation detected has been in harmful quantities since the decontamination process, which has been ongoing for decades.

“Artists have walked around with Geiger counters,” Ockel said. “But they’ve found nothing.”

A hulking crane—taller than the Statue of Liberty and as heavy as the Eiffel Tower—remains a permanent reminder of that era, as the gantry crane was constructed in 1947 to switch out gun turrets on battleships at some of the largest dry docks in the world.

The artists assembled in the shipyard use the landscape as both inspiration and subject matter. Artist Randy Beckelheimer, who has been working in his studio overlooking the bay for three decades, nearly exclusively paints images of the shipyard and surrounding neighborhood.

“If I’d kept my old studio, I’d still be painting red squares,” he said, referring to the abstract style of works he made in his previous space on nearby Yosemite Avenue.

Artist Stacey Carter paints the shipyard and uses large-scale archival photographs to create custom art pieces. She’s also become an informal historian of the site, offering walking tours and sharing photographs with family members whose relatives worked at the military outpost but never knew about—or understood—their parents’ jobs.

“Either they weren’t allowed to talk about it or they just didn’t know,” Carter said.

The artist community first took root in the 1970s, when a commercial shipyard leased the site and began subletting space. Sculptor Jacques Terzian rented a studio in the 1980s and began recruiting other artists to join him.

Some of those original artists are still there, like Lorna Kollmeyer, who runs the last plaster shop in San Francisco. “The only reason we’re still here is because of the shipyard,” she said.

Realizing they had created a white community of artists within a Black neighborhood (“It didn’t feel right,” Ockel said), the Shipyard Trust for the Arts began its artist-in-residence program in 1995 to draw in creators from the surrounding community.

The first participant in the program, Malik Seneferu, had never heard of the concept of an artist in residence. “I thought I was going to live there,” he said. Seneferu—who calls himself a renaissance artist, proficient in every genre—has since made 10,000 pieces of art at the shipyard, continuing to rent a studio after his residency was complete. Growing up in Hunters Point, nicknamed “The Hill,” he has a deep connection to the topography, which he uses in his series “From the Hill and Beyond.”

As a teenager, Seneferu would watch the sunrise from his bedroom and dream of what could be beyond the hills. “I’ve always loved imaginative landscapes,” he said.

The site has long been fruitful for imagination. The late sculptor Richard Serra’s father worked as pipe fitter in the shipyard, and he took his 4-year-old son to work to watch the launch of a ship. A young Serra, who would later become renowned for his hulking metal scupltures, watched the ship’s weight transform from massive on land to buoyant at sea. Looking back, he said that “all the raw material I needed is contained in the reserve of this memory.”

In a city as expensive as San Francisco, where artists seem to be squeezed out of every nook and cranny, the shipyard remains a singular place for creators to be marooned.

“We’ve been very fortunate to have our own little torpedo training center,” Kollmeyer said.

Shipyard Open Studios

- Date and time

- April 27 and 28, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.