This is The Looker, a column about design and style from San Francisco Standard editor-at-large Erin Feher.

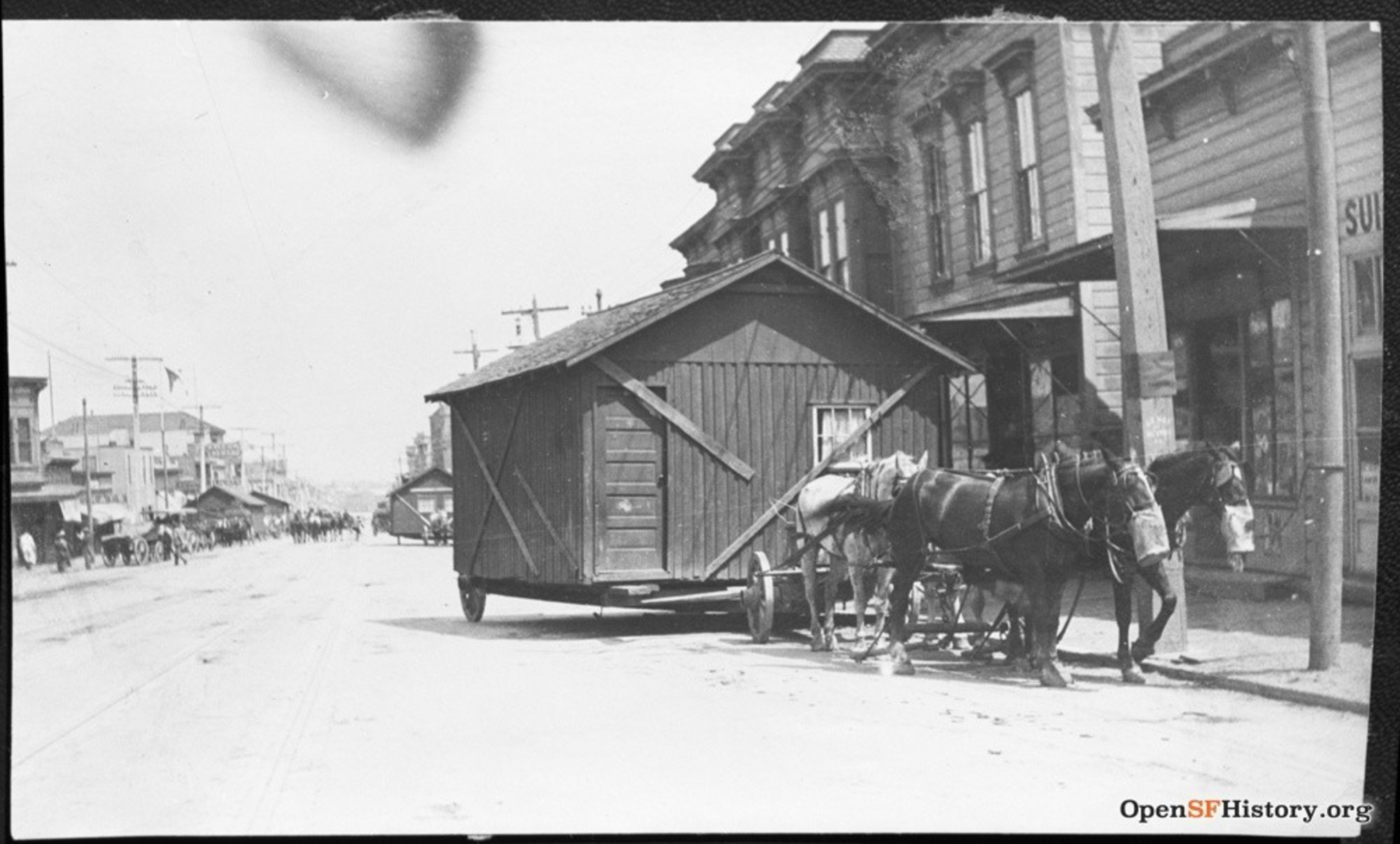

On the northern slope of Bernal Hill sits a tiny blue shack that has been a place of refuge for more than 115 years. It was built in 1906 with a speed and efficiency unfathomable in present-day San Francisco, one of 5,300 miniature emergency homes the city constructed within six months of the great earthquake and fire to shelter the newly houseless through the winter. The homes were arranged in tidy rows in parks across the city, from the Presidio and Golden Gate Park in the west to Precita and Dolores in the east.

Rent-to-own tenants were charged $2 a month toward the $50 total price of building each cottage. After paying it off, the proud owners were required to move their structure out of the park to somewhere more permanent. Eugene Edward Schmitz, San Francisco mayor from 1902 to 1907, famously said: “I’m only afraid these people will never want to leave their new homes here.”

He could have been talking about David Benzler (opens in new tab), an artist and sign painter who has lived in the blue shack on Folsom Street for nearly 15 years. Starting its life in Precita Park before being hauled less than a block up the hill sometime later, the shack was most recently purchased in 2022 alongside a larger home on the same lot.

Benzler came with the rent-controlled unit, which itself has a long history of being passed between parties, from ex-girlfriend to friend, boyfriend to former lover, usually after a relationship dissolved or passion dimmed — the occupants using the earthquake shack to lick their wounds and rebuild themselves after surviving their own personal shakeups.

Benzler can rattle off at least half a dozen names of folks who came before him. He was offered the place by a friend, the writer Andrew Leland, after splitting from the mother of his child. He wanted to stay close to her place in the neighborhood but needed some solitude — and an affordable rent.

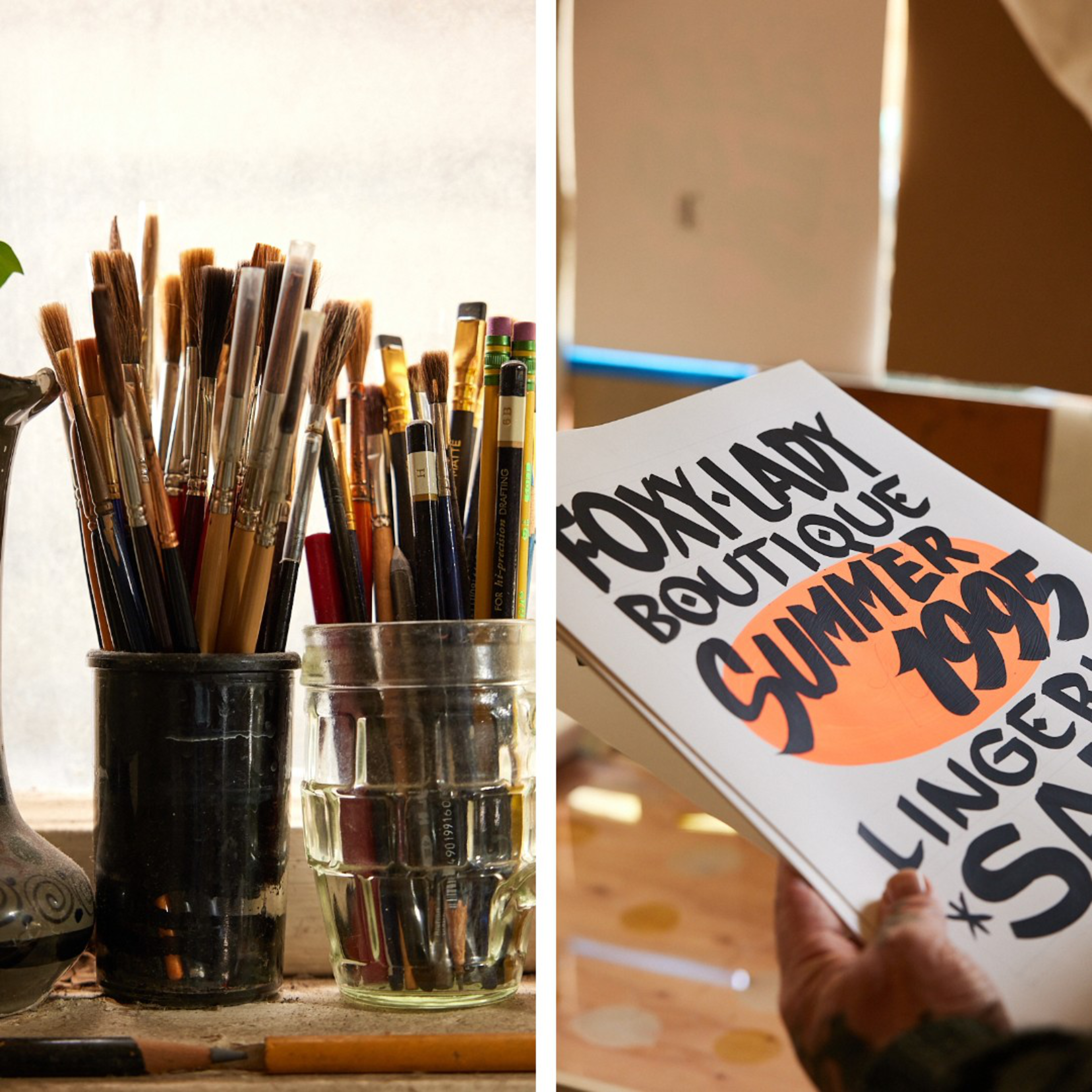

Like a sturdy little flower pot, the house practically blooms with Benzler’s creative output. The street-facing front window is a collage of his bright, graphic, hand-painted signs, whose topics range from the political (“Protect trans youth”) to the prosaic (“Ground beef $5.99”).

A step over the threshold reveals his painting studio, where a collection of quiet and contemplative landscapes in various stages of completion are propped up, and tubes of oil paints are piled, neatly rolled and labeled.

The 230-square-foot free-standing house is laid out with a sharp and efficient geometry: There are two main spaces, each roughly the same size, and two smaller cubbies in the rear: one a bathroom; the other, a closet. The front room holds the sun-dappled art studio and kitchen. (Benzler’s larger sign painting studio is a quick bike ride away down Folsom.)

The rear room serves as his bedroom, with a writing desk, record player and shelves nearly buckling under his vast collection of sign-painting manuals, art history tomes and sketchbooks. Two walls display a salon-style gallery of local talent, with dozens of canvases by John Dwyer (opens in new tab), Caitlyn Galloway (opens in new tab), George Crampton Glassanos (opens in new tab), Tanner Frady (opens in new tab) and others, alongside a pair of guitars that are in frequent use.

Benzler insists that, given the choice, he wouldn’t opt for more square footage. “I’m like a lizard or a shark. If you put them in a bigger cage, they just grow to fit their habitat.”

He’s referring to both the size of his artwork, much of which is no bigger than a standard letter, and his material possessions, which are tightly culled and fastidiously organized. “Bigger is not necessarily better,” he says. “I think that there can be a lot of power in something that’s concise, intimate and scaled down.”

In the way of many artists, Benzler is contrarian. He sees around and through the things that distract and obscure the darker state of existence: material obsessions, technological crutches — the whole capitalist soup we’re swimming in. In other words, he doesn’t aspire to homeownership, or even a spare bedroom.

“I feel like there needs to be at least an inclination toward a nonconformity in order for you to create something useful and beneficial to an actual culture,” he says.

Benzler’s landscapes are slices of his surroundings: a garage door framed by a flowering bush, a cemetery at night, a shipwrecked and decaying boat at Nick’s Cove, the facade of a nondescript Outer Avenues house with peeling gray paint. Benzler calls them “banal,” but it’s clear he finds deep inspiration in his surroundings.

“I still walk outside my door every day, and I’m like, wow, this is a really beautiful place. And I like it here,” he says.

Benzler says he grew up poor in the Inland Empire in Southern California and lost a chunk of his youth to incarceration. In the early ’90s he made his way to San Francisco and the California College of the Arts. While he lasted only a year in the school, he never stopped making art, from writing poetry to painting political murals in Clarion Alley.

How he has been able to stay in the city is the story of another evolution. He started painting signs 12 years ago, with a stint at the iconic SoMa shop New Bohemia Signs. After a few years, he struck out on his own (opens in new tab), picking up clients around the city, with a dense cluster near his own backyard: Bernal Cutlery, Discodelic, Fiat Lux, Tantrum, Grand Coffee and The Aesthetic Union all proudly display Benzler’s hand-painted signs and window art.

Like many artists, he has strong feelings — and strong words — about the coupling of art and commerce. But he knew that with a child to support, he had to make it work. “What I love about sign painting is that it is a service-driven endeavor,” he says. “It’s a way to delineate my own agenda and serve a greater purpose.”

He likes belonging to an ecosystem of small businesses, part of the support crew for folks hacking it out in corner stores and sidewalk stands across the city. Recently, one of the Mission’s beloved street taco shops, Tacos de Canasta, was forced to move from its longtime spot on 24th and Folsom streets when the owner of a new brick-and-mortar restaurant complained.

“They are this middle-aged couple in their 60s, they’re selling tacos for $2 a piece,” Benzler says. He presented them with a hand-painted sign after he heard about the situation.

He considers such people, and what they do to make it in San Francisco, whenever he’s asked about leaving the city. “Look, I’m a white, straight dude in 2024,” Benzler says. “Maybe I shouldn’t go somewhere else and plant a fucking flag.”

He reflects that he’s been here, in his tiny blue house, longer than he’s been anywhere else in his life. “Maybe I should do the opposite. Maybe I should stay here and help somebody else out.”