I am on a Zoom call late Wednesday morning when I think I hear notes being played on the piano downstairs. A neighborhood cat must have come in and walked on the keyboard, I think. The back door is open, as it usually is, so Nala, our pit bull, can come and go during the day. I keep talking but wrap up the call early and go downstairs.

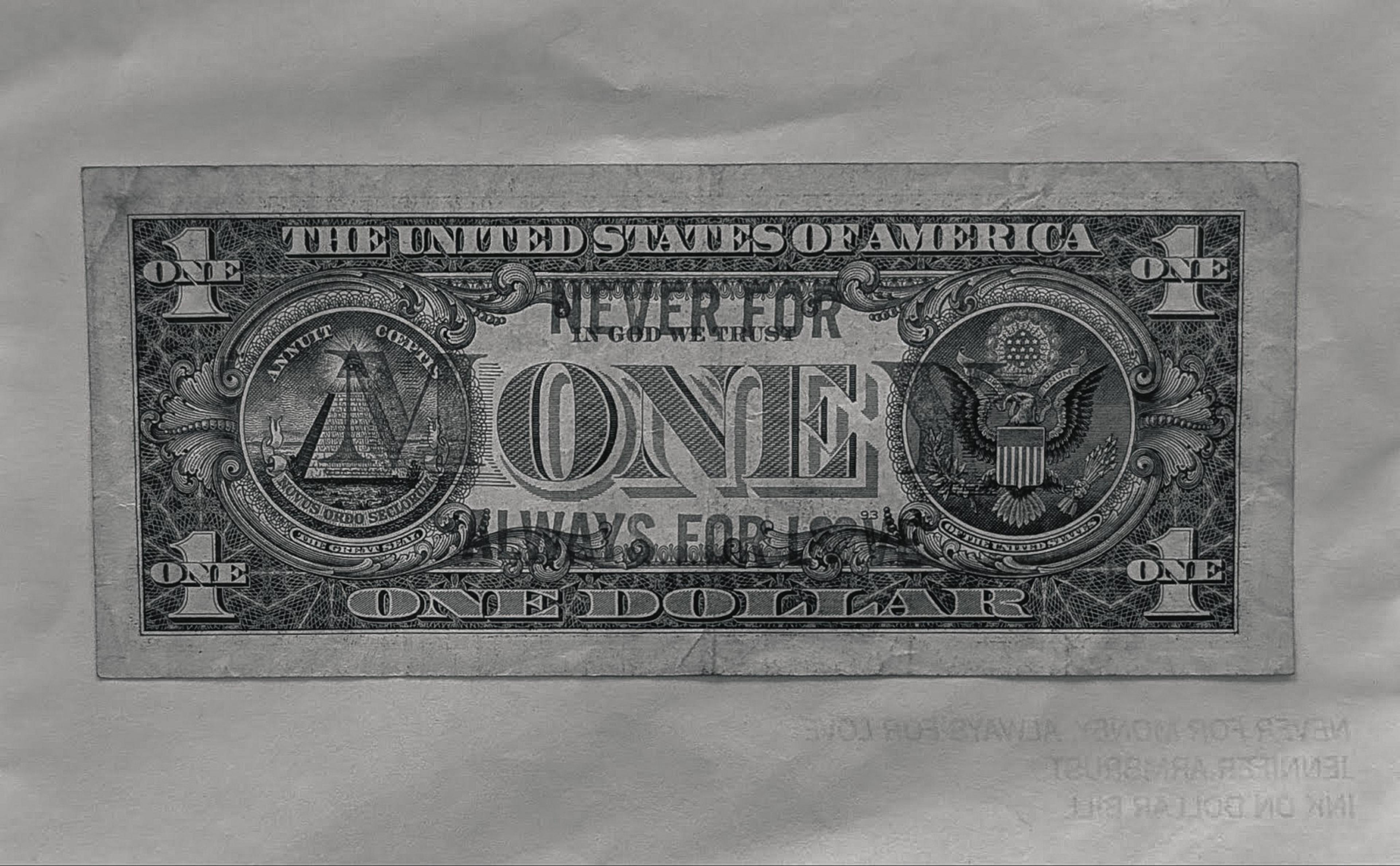

In the kitchen, something catches my eye. On the shelf under the spices, where the water glasses live, in one of those plastic sleeves that nice cards come in, there is a laminated dollar bill onto which someone has stamped letters to make it say

NEVER FOR

MONEY

ALWAYS FOR LOVE

This is a line from “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody),” a song by the Talking Heads. It is my favorite song.

I take a picture and text it to my best friend, who’d been over the previous night, and to my husband, who is in London. My friend texts back: WHAT? No, I didn’t leave that there. No, it wasn’t there last night.

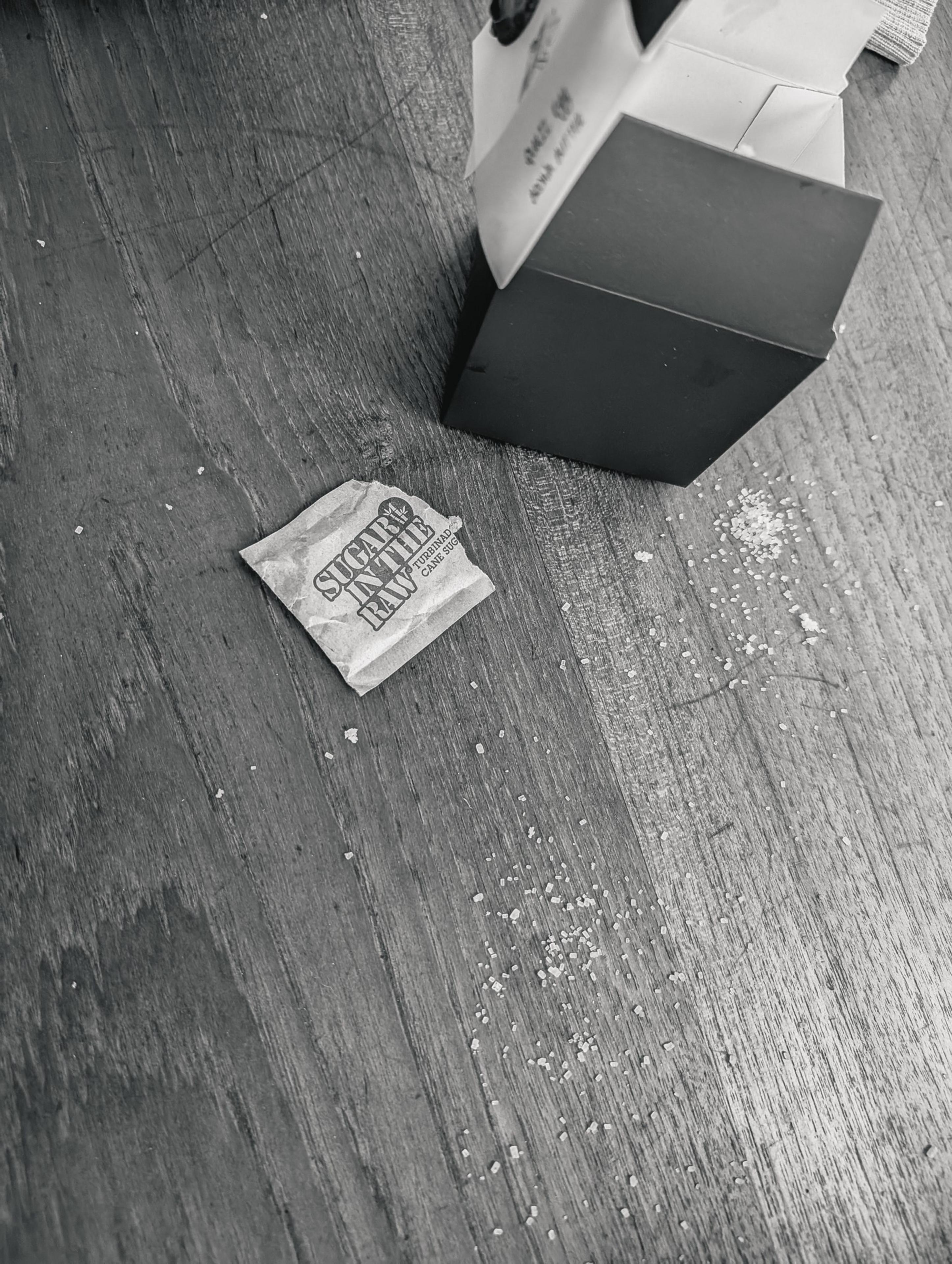

Then I notice that the little box on the kitchen counter with a piece of cake is open. I peek in. The cake is gone. A packet of sugar has been torn open and spilled across the counter. I start to clean it up. No, wait, don’t do that. I should leave it. What am I doing? Who is here?

The carton of milk is out on the counter. Had I left it out? I pick it up. It feels light, nearly empty. Was it low before? Maybe? Doesn’t matter. Who put the “Never for Money” thing on the shelf? Has a dear loved one come to visit unexpectedly? Or is someone threatening me? Or am I just going nuts?

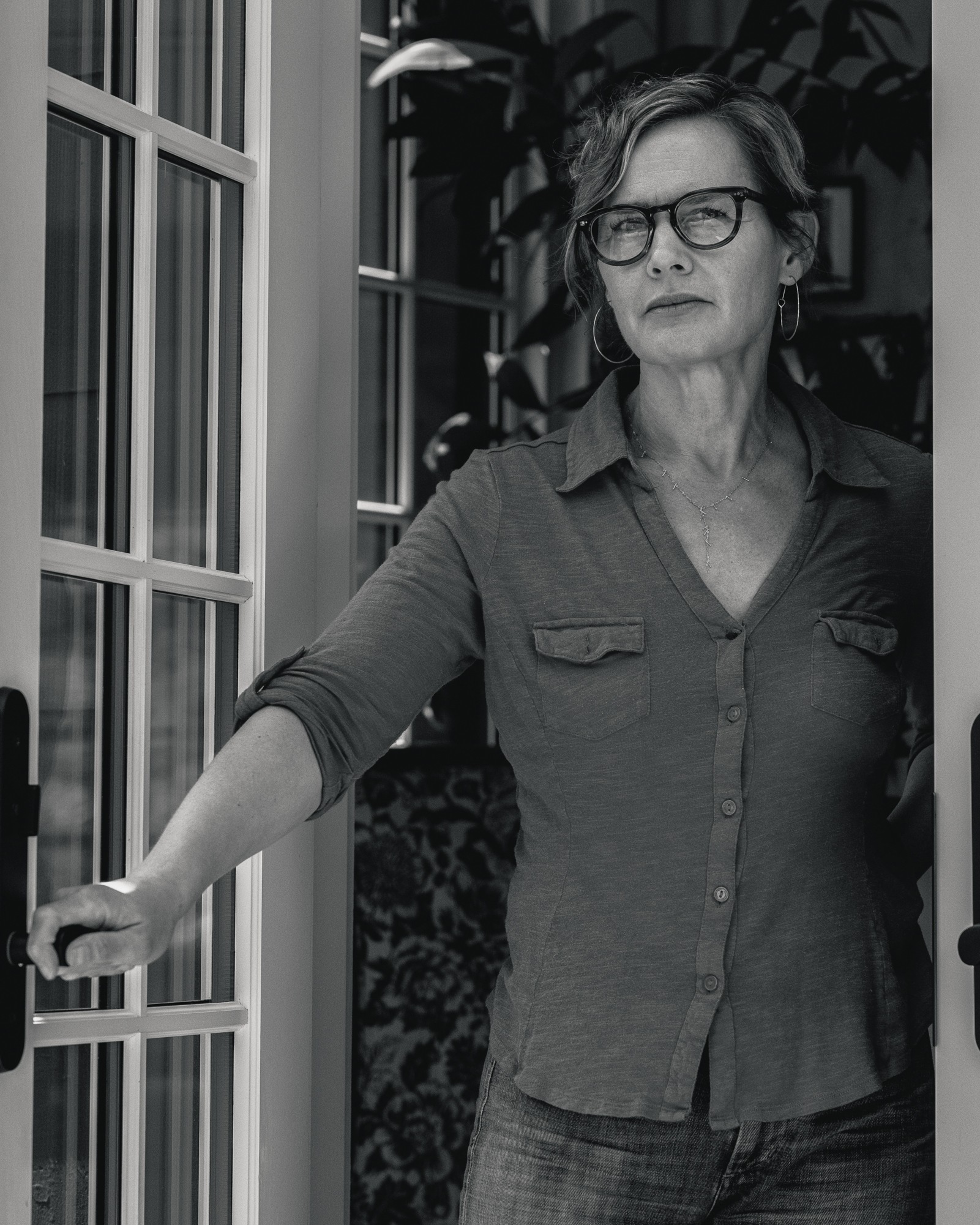

I lock the French doors at the back of the house. I lock the front door with the chain, which I never do. I check the door that leads from the kitchen to the driveway. I make myself a cup of tea and add the last of the milk. I call the Oakland Police Department’s nonemergency number.

The phone tree has a lot of options and, for many of them, the voice gives a number to press and spells out a long URL where you can get more information online. It’s slow going. After about five minutes, I realize I’ve spaced out. It’s noon, and I have another call. I go upstairs and resume the march of the Zooms.

While I’m on my noon call, my husband texts back from London. Yes, he writes, someone gave me that dollar bill years ago. It was in my drawer under my work station. In the drawer where you keep your stash of cash? Yes, that one. Where did you find it?

I end the meeting a minute early and go downstairs. The cash in my husband’s drawer is gone. I have a 1 p.m. Zoom, so I go back to the office, tucked in a far corner upstairs.

The meeting is over. As I head toward the stairs, I hear a sound in the bedroom and go in. There he is: a young, tall, very blond man, going through the plastic baggie I had thrown jewelry into when I came back from the East Coast last month. The dresser drawers are open. I’m seeing him in profile, but he turns to me, and his expression is one of frustration. Why am I interrupting him, he seems to say. What the hell am I doing here?

At that point, my brain and my body split. In my mind, I’m calmly but firmly asking him to put my jewelry back (has he actually taken any? none of it is worth anything) and leave immediately. But my body has done something else, because now I am pounding desperately on Jason and Anna’s door, two houses down. At least one of them usually works from home, but I’ve forgotten they are away. Maybe Diana across the street, I think, and it’s only when my feet feel the rough pavement that I realize I’m barefoot. I am holding my phone, and I have dialed 911, and there’s a message quietly playing about someone being with me as soon as possible. What am I going to say? I vaguely recall being in my bedroom, being yelled at by the young blond man, with great irritation, in a language that sounded Slavic. Was it Russian? He looked a bit like Rutger Hauer in “Blade Runner,” but dressed for a MAGA rally instead of a dystopian futuristic Los Angeles.

Diana’s not home either, but from her front porch I have a perfect view of the door to our kitchen. Rutger (he needs a name, so why not?) has come out of it and is standing next to my car. There’s a pillar on Diana’s porch, and I attempt to hide behind it, but I’m like a toddler who thinks that because I can’t see you, you can’t see me. I must look ridiculous. I jump off the porch, and I’m now behind Diana’s butterfly bush, a lattice of stalks and blooms that used to have a lot more foliage. I can see Rutger perfectly. And of course, he can see me.

But Rutger isn’t coming at me. He’s just standing there by my car, saying something I can’t hear. He seems frustrated again, and angry that I don’t understand him. After 10 seconds or five minutes, a black sedan pulls up with the window down. “Are you OK?” a woman asks from inside. “I heard screaming.” Had I been screaming? “No,” I say, “I’m not OK. Can I get in your car?”

“Just drive,” I plead, once inside. We go a few hundred feet, and I ask her to pull over. Her name is Jessica. She lives in the apartment building next to Diana’s house. Her husband, Dao, is home, and she’s texting him. Dao texts back: He can see Rutger standing there, pumping his hands in the air, immensely frustrated with how we are all handling this situation.

I look at my phone. I am no longer on hold with 911. Did I hang up? Did they drop me? I dial it again. It rings, then hangs up. This is somehow not surprising. I’ve read the stories. Oakland has the second-slowest 911 response time in California (opens in new tab), a state not exactly known for stellar public services. People routinely get a busy signal when they call.

Many in Oakland just don’t bother with 911 anymore. They turn to whatever other resources they might have: private security, surveillance cameras, a gun. For the moment, I have Jessica and Dao. I’ve never met them before.

Dao texts Jessica to say that Rutger has finally moved on. He has walked to the corner and started down the hill toward Lakeshore. But now he has stopped. He’s just sitting on the curb, pumping his fists in the air again. Jessica turns around, and we drive the very short distance back to my house. I go in. My eyes are jumping around. What has moved, what has changed, what’s missing? A door slams, and I jump. Oh, shit, the door to the laundry room. The wind has pushed it shut. I hadn’t checked that it was locked. That’s how he got in. He came into my house, ate my food, took my husband’s cash and left. Then I let him right back in.

Once, when I was in high school, one of the drunks from the block came in. Our home, a 1920s brick row house in the northernmost neighborhood of Manhattan, faced Inwood Hill Park, and the park benches were a favorite spot for drinking cheap liquor out of paper bags late into the night. (Lin Manuel Miranda of “Hamilton” fame grew up a block north, in an identical brick row house. If you’ve seen his “In the Heights,” you’ve seen my neighborhood, but with the color saturation jacked up.)

These regular drinking confabs were just part of the scenery. But one night, one of the regulars was standing in our living room. The way I remember it — and this was a long time ago — my mother and sister weren’t home, but I had a friend over, and we had probably forgotten to lock the door. I had no choice but to confront this intoxicated, middle-aged man, sputtering aggressively but incoherently. I remember pushing him out to the foyer and locking the door. He was big but too drunk to resist with any real vigor.

For years afterward, I would dream about locking the door and then him coming through it anyway, as if it had magically unlocked itself. I still have that dream occasionally. It’s always that exact door, that exact jimmy-proof deadbolt that made that distinctive thunk when you locked it. Everyone in New York had at least one, sometimes several, unless they lived in a doorman building.

But then and now, locks do not magically unlock. People (OK, me) leave them unlocked. I am not mad at myself for leaving the back door open. I’ve lived in this house for 22 years, and having the French doors thrown open to the deck in good weather is one reason I love it. The day has been beautiful. But I had known someone had been in my house, and I had failed to secure it.

Now I am standing by the door I’ve just closed. I try 911 again, and while I wait on hold, I try to sort out what has happened. On the cafe table, there are a handful of my daughter’s pencils and a few small watercolor paint brushes laid out neatly. On the deck beneath the table, a wrapper for a hastily opened tin of sardines has been carelessly discarded. Oh, good, I think: We had too many sardines. We always think we’re going to eat them and then don’t. And then I look at the pencils again, and I feel a little sick.

Later, I get calls and texts from many friends, checking in on me. It’s a violation, they say. You must feel so violated. By then, I don’t. I know I don’t because teenage me, pushing a drunk man out my front door, did feel violated. Did anyone say, “You must feel so violated?” I don’t think we said things like that back then. I was also choked and mugged on the platform of the 81st Street subway station around that time, but I never had nightmares about it the way I did about that lock. Fifty-four-year-old me feels violated only on behalf of my 21-year-old kid, whose art supplies have been touched by a stranger. It’s only the pencils that make me shudder.

I go to the front door. I had latched the chain, but now it’s off. We keep a key in the lock on the inside. It’s gone. The car key lives by the other door, the door from the driveway. I check; it’s gone too. Cabinets and drawers are open. But lots of things aren’t gone. He’s rifled through our drawer full of more stamps than we will ever use in our lifetimes and taken none of them. I’ve just switched to a new phone, and the old one is sitting on the counter, next to my watch. He could have taken my computer from the office. It’s still there.

Back downstairs, I find perhaps the strangest thing of all. He has left a note. It’s what appears to be a Slavic name, then maybe the start of an international phone number, starting with +26? Or it could be the fragment of an equation? Is this the beginning of a bad Dan Brown novel?

I am shocked to hear a voice coming through my phone. 911 has finally picked up. The report doesn’t take long: address; man in house; no physical contact; I am not harmed; yes, things are missing; a phone number they can reach me at. Officers will come to the house as soon as they can.

Jessica and Dao, my new best friends, are texting. You know he’s still right around the corner, right? Really? He has my car key. I can’t find the spare one. He’s just sitting there pumping his fists into the air. OK, I’ll call the cops again and see if they might be able to come sooner.

I call again, but all I get is “We can’t give you an ETA.” I text Dao: Should I just go politely ask for my key back? LOL. I’ll go with you if that’s what you want, he responds. Is this crazy? I don’t think he’s armed. He didn’t try to hurt me. Dao and I meet and discuss. We walk together down the hill and around the corner. The guy is gone. I’ve missed my chance.

Hours later, I’m alone in the house, still waiting for the cops. I call a friend who talks me down off the adrenaline. Come out with us tonight, she offers. I would, but I have a feeling I’m going to be stuck here waiting for the cops. Just me and Nala, who is still asleep under the deck, still oblivious.

It’s now 9:30 p.m., and they still haven’t shown. I pack a bag and drive our old beater truck to a friend’s house, since I still can’t find the spare car key. He’ll probably steal the car tonight, but I don’t know what else to do. This time, I actually lock all the doors and chain the front door. The key he has opens only that door, so he shouldn’t be able to get in.

In the morning, I go back to the house. The car is still there. I look around, trying to figure out what he touched, what he took, what he moved, but I’m out of time. I have a 7 a.m. meeting (I work East Coast hours), and I need to get back to my friend’s house, where my computer is. I’m headed back to the truck when I notice, carefully placed on the windshield, my car key.

Was that there before? When I was watching him from Diana’s porch, is that what he was doing, putting the key where I would see it? No, Dao, Jessica and I were in and out of that door a lot, and none of us saw it there. It is sitting on top of the windshield wiper, positioned to be noticed. I stand there, stunned. Rutger came back last night and GAVE BACK MY KEY.

It’s like I’m looking at the Talking Heads dollar bill again: a delightful thing made deeply creepy. Am I happy to have it back or freaked out that he was here again? What kind of home invader returns the most valuable thing he has stolen? Was that what he was trying to say while I watched him from behind Diana’s butterfly bush? I don’t want your stinking car. Come get your key, please. Could he have been trying to tell me he was sorry he had scared me? Is the car key his attempt at an apology?

I work that day from my friend’s house, go to a doctor’s appointment, have dinner with a friend. The day comes and goes without a word from the Oakland Police Department.

It’s Friday now. I’m trying to pay attention to my phone, but I miss OPD when they call at 1:30 p.m. The message says they have “officers at the scene,” but I am not there. It’s not a scene now, just a house, I silently protest. All I can do is call the number and tell them I’ll return immediately and stay around the rest of the afternoon. They don’t come back. By 7, I’m hungry and go to meet a friend for tacos, phone in hand with the ringer on full volume.

We’re just finishing dinner when my phone starts to go crazy. I’m getting texts and calls at the same time. One call is from an OPD officer: My neighbors (the ones texting) have spotted Rutger trying to get into my house again and have called 911. This time, the cops get there. They have detained the suspect a few blocks away and want me to come ID him.

Identifying him will be easy. I saw him face to face, I saw him from across the street, and I’ve seen him not only on our security footage but on our neighbor’s. He went to Jason and Anna’s house, touched and rearranged some packages and didn’t take any. He doesn’t seem to be aware of these (quite obvious) cameras everywhere, or at least, he makes no attempt to conceal himself from them. In the footage from our home camera, he loiters around our front door for a while and at one point rubs his hands together and very intentionally puts both palms flat on the windowpane next to him, leaving possibly the clearest and most complete set of fingerprints in trespassing history, so visible you wouldn’t need to dust for them.

I’ve pulled up to the flashing lights but sit in the car for a moment and try to gather my thoughts. Until this moment, the police had not visited, not taken a statement, not asked a single question other than the few the 911 operator recorded. The idea that they would actually catch the guy had never occurred to me. Now they want to know if I want to press charges. The obvious answer seems to be yes, but I have so many questions. Is he actively trying to get arrested? Is that why he came back yet again? If so, mission accomplished. I resolve not to be rushed or pressured into a decision.

I would like to talk to the suspect, I tell the officers. Why? I want to ask him why he returned my key, I say, though I haven’t really thought this through. This man was in your home, he took your things, he could have hurt you, an officer says. I know. But I would like to talk to him. He had a meth pipe on him, he says. OK, I say, but can you get a translator?

The cops seem to have pegged me as a little off. They look at me as if to say, We’re the force that didn’t make it to your house for two whole days, and you think we have a translator handy? One officer says, The guy speaks English. But he was shouting at me in something that sounded like Russian, I tell them. Polish, they say. He’s Polish. Maybe Ukrainian. But he speaks English — not well, though.

They let me talk to him. Up close, through the window of the patrol car, he looks younger than I remembered. He’s surprisingly docile. Was I expecting the man who yelled at me in my own bedroom, or the one who quietly returned my car key? I guess I’m getting the latter. I decide to start on a friendly note, so I thank him for returning the key. He sort of nods, head down, eyes up and to the side. I ask his name, twice, but I can’t understand the answer. I ask why he brought the key back. If he’s speaking English, I can’t tell. The engine of the cop car behind us is way too loud. I consider asking them to turn it off so I can hear, but I’m afraid they’ll make me end my little interview. I bark at him to speak up, like a stern grandmother. I try another question: You brought back my car key but not my house key. Why? Where’s my house key now? This time I can make out a response.

Not your key, he says. Not your house. My house. He nods. My house, he says again.

The pieces start to fall into place. When I walked into the bedroom and screamed, I was disturbing him. That’s why he yelled at me with such irritation. That’s why he leaves so slowly, plays the piano and keeps coming back. That’s why he returned the car key but kept the house key. He was pumping his fists with the frustration of being kicked out of his own house. The Talking Heads dollar bill? He was just redecorating his house. And he has good taste. We should always have had that dollar bill out.

I step away from the patrol car, and someone, a police officer, asks for my ID. The officer has the suspect’s ID in his other hand, and I get a look at it. My eye lands on his name. It’s the name he wrote on the notepad in my house. He wasn’t leaving me a note, or even taking one himself. He was marking the house as his. Maybe the handprints on the window served the same function: leaving his mark.

I ask the officer, If I press charges, what will happen to him? He’ll get a mental health evaluation. And then? It depends. If I don’t press charges, what will happen? We will release him. Like, right here? A few blocks from my house, the house he thinks is his? Yes. We can’t hold him if you are not pressing charges. But he’ll go back to my house, won’t he? Yes, the officer says, I would guess that he will.

I’m more convinced than ever that Rutger’s behavior, while criminal in effect, is the result of mental illness. And incarceration, I believe, is the wrong response to mental illness. But there’s at least a hope of getting him care once he’s evaluated. And if I let him go, not only does he not get help, but I have an unwanted visitor possibly every day I’m in Oakland. I tell the officers I will press charges.

They take my statement. I make sure to include that he brought the key back, that he never threatened to hurt me. But it’s a line drawing, not even a sketch. Just the facts. Or some of them. I answer the questions I’m asked. As I’m finishing, an ambulance pulls up. They’re putting him on a stretcher. They’ll take him away as a patient, not a criminal. Did they do this for me? To placate me? Are the optics just better, as they say? Or does it really mean something? Is there help waiting for him?

The officer, having gotten the answer he wanted, turns to me, face intense, looking right into my eyes. Now I need you to let out all your anger at me, he says, entirely serious. What? I’m not angry, I say. You must be, he says. We didn’t show up for two days. I’m so sorry. You have every right to be angry at us. You should yell at me.

My job is working with public servants, often when they’re the subject of enormous criticism. I worked in the White House when healthcare.gov launched and sputtered. I helped the state of California when 1.2 million people were waiting for their unemployment insurance benefits during the first year of the pandemic. I’m in touch with the federal government employees responsible for FAFSA, which has been the source of so much pain for students applying for financial aid this year. These people are the villains in the headlines. Up close, it’s more complicated. In almost every case, they’re doing the best they can within a broken system. It’s not news to me that our law enforcement system is broken. It’s not news to this officer either. If he’s like most of the public servants I know, he feels powerless to fix it.

I’m not angry at you for not showing up, I try to say. I’m angry at the choices you gave me. Jail him as a criminal or let him free to go back to my house. I’m not sure I believe you that he had a meth pipe on him. I don’t know what to believe.

Of course, OPD should have shown up the first time I called. Every time I’ve told someone that I’m fine, that the intruder wasn’t violent, that I’m very lucky, they say, That’s great, but you didn’t know that, and neither did OPD. They should have come. They’re right. I was lucky. Others are not. While violent crime in Oakland actually decreased during the first four months of 2024, residential robberies spiked by 118% in the same period (opens in new tab). And it’s disturbing to live in a city where 911 takes so long to pick up, where the cops don’t show up for days.

And yet, they caught him. Officers were twice dispatched to my house to take my statement after the incident, and both times a higher-priority call came in. When the neighbors reported he was on the scene again, they swung into action. Isn’t that the right way to prioritize limited resources? Is the real harm that the police didn’t show up for two days, or that they pressured me to press charges on a mostly harmless, severely delusional young man? Or is the real offense that I agreed to those charges?

Once you go to who’s to blame for OPD’s deficiencies, it’s turtles all the way down. I know this cycle. Something bad happens, and the public demands that safeguards be put in place so that it never happens again. We establish extra layers of oversight to double-check. Lots of bad things have happened in OPD for decades. Lots of remedies have been layered on. Each year, a greater proportion of the department’s resources goes into safeguards, oversight, reporting and the like, and less goes into the core functions of policing — such as sending cops to respond to break-ins. The department culture becomes increasingly focused on sheltering against the blame that falls like rain onto cops, sometimes in torrents, but always at least a drizzle. It’s a cycle no one seems to be able to stop. And no one remembers exactly where it started. But it’s outrage after failures that starts the cycle — outrage that’s merited — but ends up ensuring the very outcome it meant to prevent.

What I do know is that this officer standing in front of me, asking me to yell at him, didn’t make the rules about which crime in progress to respond to. I know, because I study this stuff, that had the officer actually come to my house the day of the incident, he would have then slogged through piles of paperwork, entering the same information into multiple systems, complying with oversight and reporting directives that date back to the 1960s (and now that he has caught the suspect, he’ll be doing that for the next few days). Maybe he decided years ago that, as a cop, no matter what you do, you can’t win, so it’s no use trying anymore. But that part I don’t know. The rest of it I’ve seen.

I return the officer’s direct gaze. I look into his eyes. I realize that after all my confusion and clarity and questions, there is one thing I haven’t said. He caught the guy who was in my bedroom. It’s not simple, but it’s true. I say thank you.

The ambulance is pulling away. I can’t see the guy I called Rutger but whose name I now know. I still have so many unanswered questions. Who is he? How did he get here from Poland? Is he, as the cops keep suggesting, addicted to meth? Or is he just, as my grandmother would say, garden-variety crazy? And did he know my name? My last name is Polish. My father’s family came to the U.S. so long ago that we have little connection to Poland, and I don’t speak a word of the language. Did he choose our house because he thought I was a fellow countryman? What does he know about me, if anything? Surely, they’re not going to put him away for very long for stealing $500, a piece of cake, a tin of sardines and my daughter’s pencils. Will I see him again? Will I understand this any better then?

I have another thought. Does he know the song? “This Must Be the Place,” from the album “Speaking in Tongues.” It’s a classic from 1983.; the guy looks like he could have been born after 2000. Still, it starts: “Home is where I want to be, pick me up and turn me round.” If he really thinks my home is his, it’s quite the message. Now he’s been picked up. Maybe he’ll be turned round. Whether he was trying to get arrested, or just delusional, or something else entirely, I don’t know. Here’s how the song ends:

I’m just an animal looking for a home, and

Share the same space for a minute or two

And you love me ’til my heart stops

Love me ’til I’m dead

Eyes that light up, eyes look through you

Cover up the blank spots

Hit me on the head

Ah-ooh, ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh

The outro is the prettiest melody you can imagine. So I play that in my head as I go back to the space he and I shared, albeit unwillingly, for a minute or two, and try to figure out what the hell just happened.

Jennifer Pahlka is the founder and former executive director of Code for America, the author of “Recoding America: Why Government is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better,” and a senior fellow at the Niskanen Center in Washington, D.C. A longer version of this essay can be found on Pahlka’s Medium page (opens in new tab).