It has all the makings of a great mystery: a trove of abandoned artworks, a victim of the Holocaust, a lone clue leading to Huntsville, Ala., where Nazi scientists once worked in secret for the U.S. government.

Yet it’s not a detective novel or a Netflix show — it’s real life, and it happened in San Francisco, as detailed by The Standard in a series of mystery-unraveling reports published this year. Now, the subject of that investigation will be on full public display Aug. 14-18 in the Grand Hall of San Francisco’s Ferry Building, in the exhibition “Rediscovering the Art and Life of Ary Arcadie Lochakov.”

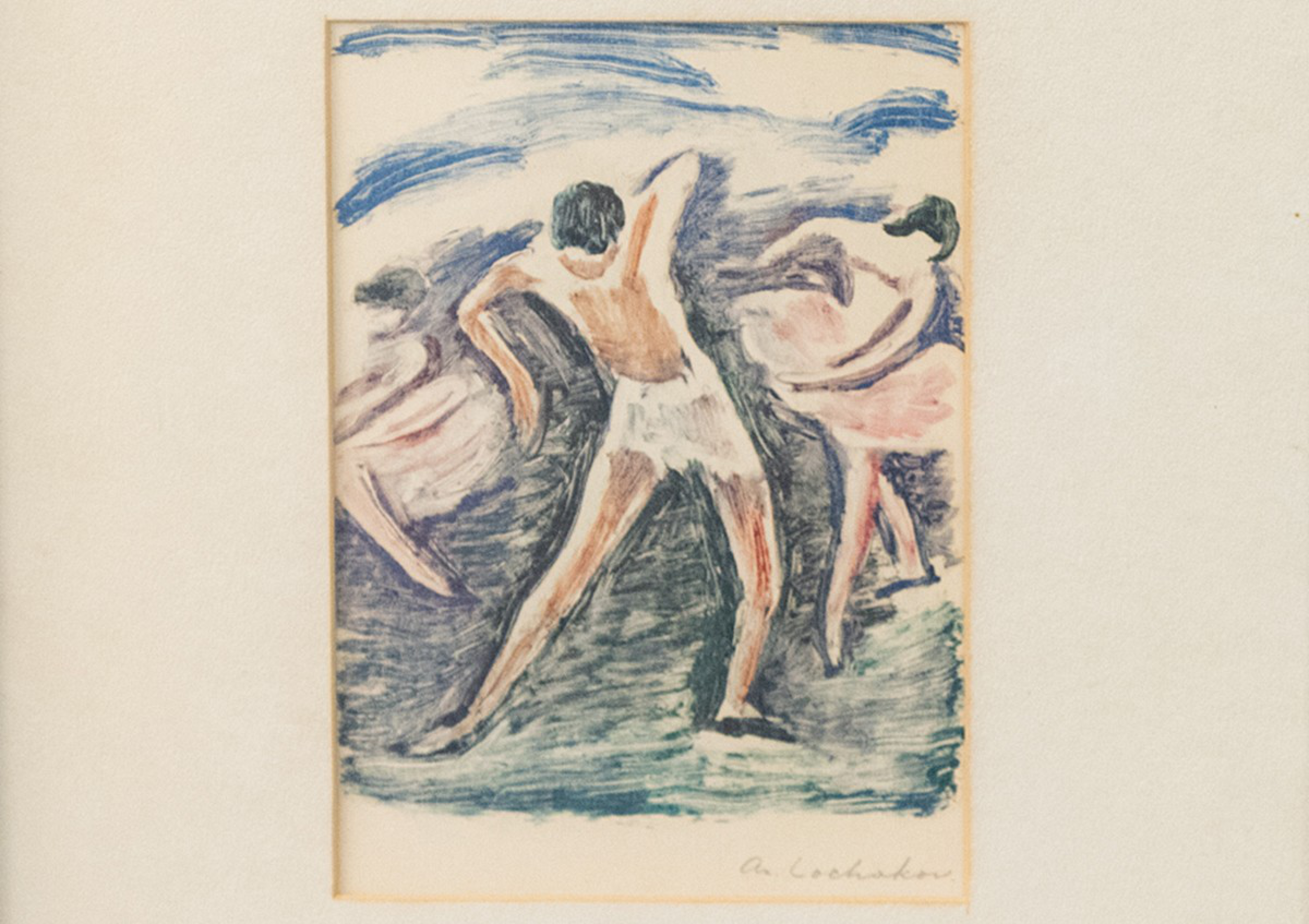

But first, a reminder of how the saga began. It was a sunny morning in May 2022 when Joseph Jermaine, a general labor supervisor for the Port of San Francisco, came across a remarkable find: a trove of 48 artworks carefully arranged on a cement bench in Crane Cove Park in the Dogpatch. Many of the artworks were framed, and the majority were signed with versions of the same name: Ary Arcadie Lochakov.

Jermaine considered tossing out the artworks, but sensing that they had a provenance worth investigating, he alerted his colleague Arianna Cunha, who took them back to the port’s offices. A closer examination sent her on a serpentine research path spanning two years. With the help of art historians on two continents, Cunha learned that Lochakov was a Jewish artist, a member of the famed School of Paris, which included Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso.

Lochakov died in 1941, when Paris was under Nazi occupation.

So how did such a large body of his work end up on a park bench halfway around the world more than eight decades later? And who left it there to be discovered? “There’s a lot of things we will never know,” Cunha said. “But you can embrace the questions and enjoy the mystery.”

When the Port of San Francisco in January passed a resolution to transfer the works to a suitable permanent home, The Standard was the first to report the story and piece together the collection’s path from Paris to Huntsville, where many of the works were framed, to San Francisco — while also reporting on new, reader-sourced discoveries. Now, Lochakov’s works will be on public view in San Francisco for the first and only time before they make their way to a permanent home: the Museum of the Art and History of Judaism in Paris.

All of the discovered artworks — including the 10 not signed by Lochakov — will be on display at the Ferry Building, about 3 miles from where they were discovered two and a half years ago. “Like many things surrounding this art, it’s been a journey,” said Eric Young, communications director for the port, about the process of organizing the exhibition. “We are not an art museum; this is not what we do,” Cunha added.

Lochakov’s work will be displayed thematically at about a dozen stations, with descriptive texts accompanying the pieces and contextualizing the period of their creation. The port partnered with curators from San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum, who provided guidance on handling and mounting the pieces, as well as arrangement suggestions.

A short video on a loop will feature interviews with people connected to the Lochakov story and its twists and turns. “The confluence of coincidence makes this story so unique,” Young said. “It’s a trajectory so unusual and so fortunate.”

Amy Kerner, a curator at the CJM, reviewed the captions for the artworks. “The Lochakov story demonstrates the contingency of Jewish artists’ legacies and the power of individuals — collectors, port employees, journalists — to decide how to narrate and make sense of those legacies when new artworks come to light,” she said.

Kerner discovered that some of the artworks were attached to their backings by torn stamps, possibly by Lochakov himself. The use of stamps as makeshift tape could point to the uselessness of sending mail during the war, Kerner said.

Cunha said new information — like details about Lochakov’s previous exhibitions — will be shared in the display, which she sees as a celebration of many people working together.

“It’s as if this was meant to be,” she said. “Like there was some sort of divine intervention.”

Both Young and Cunha count Lochakov’s intense woodcuts among their favorites of the works. “I have a physical emotion just looking at them,” Cunha said. “It was such a dark time, with his portrayal of terror.”

She sees a “confluence of coincidence” in the throughline that has brought Lochakov’s legacy back to life.

“He needed this story to be told,” she said. “It feels like it was him all along — like he was saying: These are the people I need to tell this story.”

“Rediscovering the Art and Life of Ary Arcadie Lochakov” will run Aug. 14-18 on the second floor of San Francisco’s Ferry Building, 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. Wednesday through Friday and 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Admission is free.