A San Francisco department head signed off on multiple six-figure contracts directed to a nonprofit led by a man with whom she shared a home address and car, The Standard has learned.

In 2021 and 2022, Sheryl Davis, the city’s Human Rights Commission head, approved contracts worth a total of $1.5 million with the local nonprofit Collective Impact, which is run by James Spingola. In interviews, the pair acknowledged having a close personal relationship, which Davis has never formally disclosed — despite rules that require such a disclosure.

After presenting evidence of the relationship to the mayor’s office, The Standard was informed that Davis has been put on leave. The mayor will be naming an interim director for the Human Rights Commission.

In a statement on Thursday, Breed’s challenger in the November election, former Supervisor Mark Farrell, called for Breed to fire Davis. He also called for a federal investigation into the Dream Keeper Initiative and Breed’s role in the program.

In fall 2022, after signing off on the $1.5 million in contracts, Davis wrote a letter (opens in new tab) recusing herself from working on grants related to Spingola’s nonprofit. Although she did not mention her connection to Spingola in the letter, she wrote that she wanted “to avoid any concerns about favoritism,” adding that she led the nonprofit herself before taking her city job.

Since then, her department has continued to issue contracts to Collective Impact, which runs programs for low-income and at-risk youth in the Western Addition. Davis signed off on funds for the nonprofit to distribute as mini-grants to small organizations in the Black community, and to support those groups with organizational development.

While city employees don’t need to disclose (opens in new tab) a “mere acquaintance” who has a financial interest in one of their decisions, they must flag the relationship if it involves a “family member or a personal friend,” according to local regulations (opens in new tab).

Paul Melbostad, who served on the city’s Ethics Commission from 1995 to 2003, called the implications of the relationship between Davis and Spingola “quite serious” and said that they were “definitely” a violation of the city’s disclosure requirements.

“Clearly, if you live with someone, regardless of whether you’re in a romantic or sexual relationship, this goes so far as she would even personally benefit,” said Melbostad. “If [Spingola’s] organization gets more money, then they have more money to pay its executive director, which means more money coming into her household.”

The dynamic between Davis and Spingola raises transparency questions about the Dream Keeper Initiative, a headline project of Mayor London Breed that has come under scrutiny for how city funds have been managed and spent. While multiple city departments have been involved with the program, Davis and her Human Rights Commission staff have led much of the effort. Last week, Davis herself called for an audit of the program.

‘We both use that address’

Davis and Spingola both registered to vote at the same home address in spring 2021, according to public records. The pair also currently co-own a 2008 Mini Cooper, which is registered to that same address, according to the Department of Motor Vehicles.

“I can’t speak to the veracity of the allegations, but if proven true, they would clearly be stark conflict-of-interest and self-dealing violations,” said Board President Aaron Peskin.

Asked about the nature of his relationship with Davis, Spingola described it as “nothing romantic,” adding, “she’s a great, great friend of mine.”

“It’s nobody’s business,” Davis told The Standard when asked about her relationship with Spingola. “Ultimately, he and I have worked together. We have a long-standing relationship. I’m not going to get into what type of relationship.”

Asked whether the pair live together, Davis declined to “confirm or deny” where she lives. “You can say we both use that address,” Davis said.

Spingola said that the pair did not live together, but declined to provide where he lives permanently. When asked about the address that he and Davis shared, Spingola said, “I do have my own room there. I do go there.” As to whether Davis also has a room in that home, Spingola said, “I guess, yeah.”

Previously, San Francisco officials have landed in hot water over mixing personal relationships with city business.

In 2018, Public Health Director Barbara Garcia abruptly resigned (opens in new tab) after her department awarded a seven-figure contract to her wife’s nonprofit, raising disclosure concerns and sparking a conflict-of-interest investigation. Three years later, the Ethics Commission fined Breed (opens in new tab) for failing to disclose the fact that Mohammed Nuru, the former Public Works head who is now in prison on corruption charges, had paid for repairs to her car. Breed and Nuru dated briefly two decades ago and remained close friends in the years since, the mayor said (opens in new tab). Last year, prosecutors accused the head of a San Francisco grant program of taking bribes from a businessman she once dated in exchange for city contracts.

Melbostad said the situation with Davis is worse than some of these past scandals because of the amount of money involved.

“This is even much more serious than Nuru paying for Breed’s car repairs,” he said.

‘Approved on my end’

The Dream Keeper Initiative was first proposed by Breed, Supervisor Shamann Walton, and other city leaders in July 2020 to redirect funds toward economic and cultural development in San Francisco’s Black communities.

Since then, city leaders have budgeted nearly $300 million for the program, about $140 million of which has been spent, according to data from the controller’s office.

In a statement, the mayor’s office said that Breed is “committed to ensuring the integrity of the program and continuing the good that it does with full transparency.”

In total, the city paid Spingola’s nonprofit $7.5 million through the Dream Keeper Initiative. That makes it the second-highest recipient of Dream Keeper funds among the nearly 350 participating organizations and individuals, according to data from the controller’s office.

When The Standard first asked Davis about her relationship with Spingola, she said she was not involved in the contracting process for his nonprofit, Collective Impact.

“I don’t review James’ contracts, I don’t sign them,” Davis said.

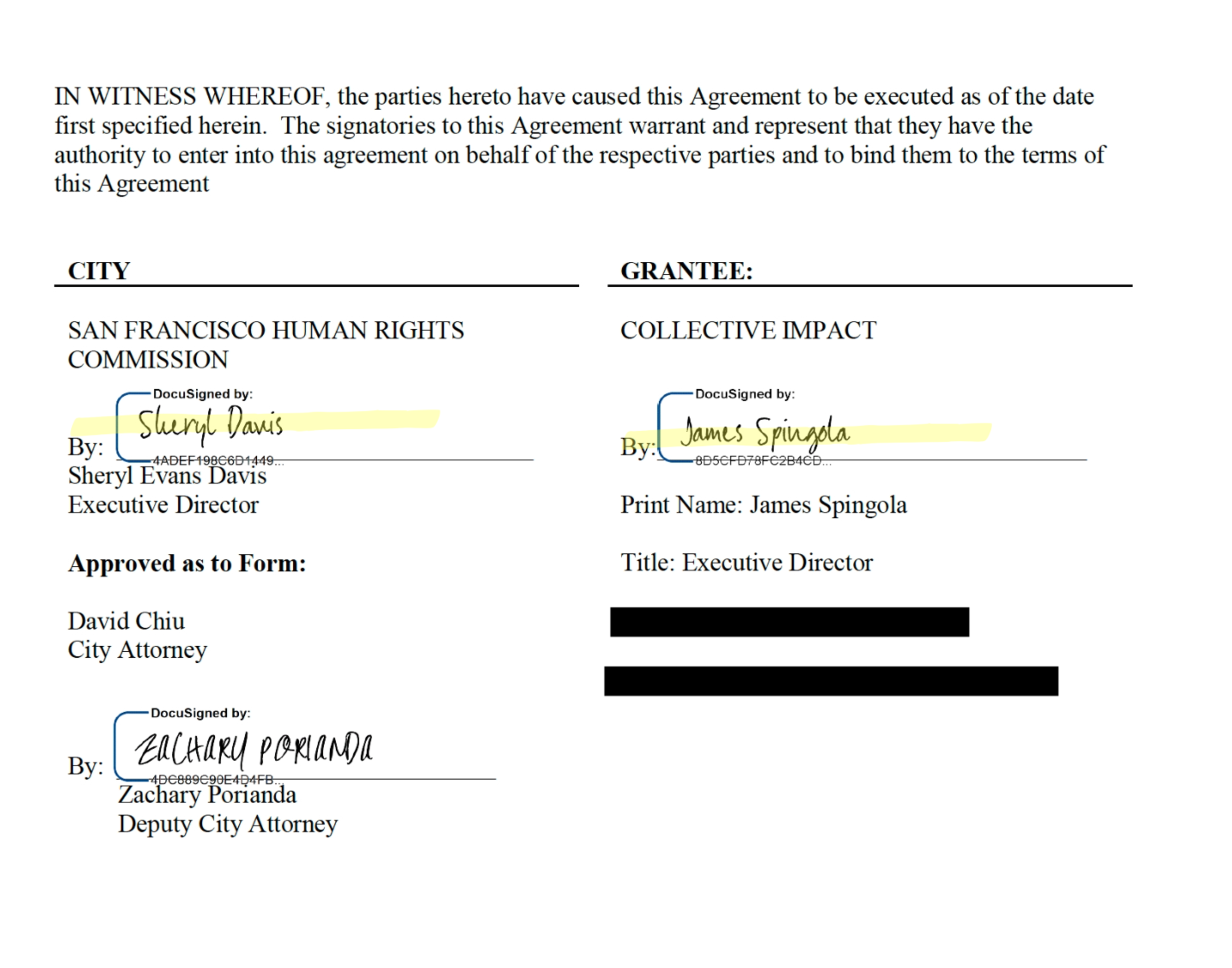

However, The Standard identified three agreements totaling $1.5 million between the city and Collective Impact, which both Davis and Spingola signed.

- July 2021 (opens in new tab): $575,000 to distribute as mini-grants to small organizations in the Black community

- April 2022 (opens in new tab): $225,000 contract to engage Black leaders to help provide grant writing, fundraising, and other organizational skills for the Dream Keeper Initiative

- June 2022 (opens in new tab): $700,000 extension to the mini-grants contract

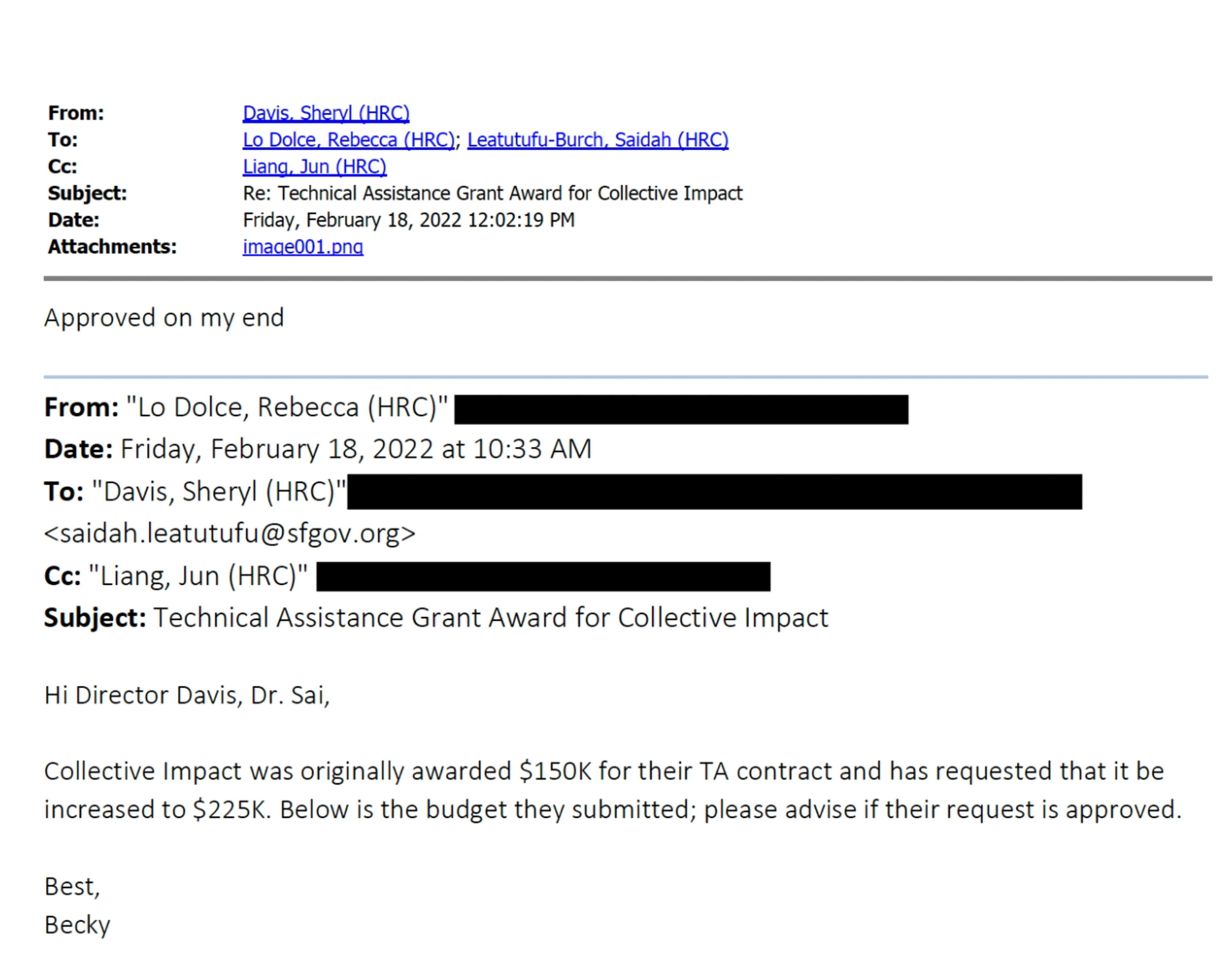

Records uncovered by The Standard also show that Davis communicated with her staff about a Spingola contract request.

On Feb. 15, 2022, Spingola emailed (opens in new tab) a Human Rights Commission staffer asking for the department to increase the budget on a contract. Three days later, that staffer emailed (opens in new tab) Davis about the requested increase, which would bump the approved $150,000 budget up to $225,000.

“Approved on my end,” Davis replied.

In a follow-up statement provided to The Standard, Davis maintained that she had never given any individuals or organizations preferential treatment.

“There are people in my life to whom I’m not related but who are close enough for me to consider family, some of whom I have worked with over many years in service to community,” Davis said. “But to be clear, this has never impacted or affected the way I manage any aspect of the work of the city department I lead.”

“If I have erred, it was in not knowing I should have made a formal [recusal] earlier than I did, even for the appearance of impropriety, to wall myself off from any decision-making related to funding administered to an organization I was so closely connected to for so long,” she said.

‘They crucify her’

Spingola said that he’d known Davis for more than a decade, dating back to the years when they worked together at Collective Impact. (Davis was Collective Impact’s executive director until 2016, and Spingola stepped into that job in 2020, according to tax filings.)

In recent years, Spingola said, Davis had been a confidant, helping him through tough times. He described her as a passionate leader who has poured her life into taking care of her San Francisco community. Spingola took issue with people raising questions about the pair’s relationship.

“This is how people repay her: They crucify her,” Spingola said. “It’s wrong for people to do her like that.”

Spingola denied that he and Davis owned a car together, saying that the Mini Cooper belonged solely to Davis. Spingola said he was listed on the DMV records because he was “helping [Davis] out on the registration,” and that they used the vehicle when the pair worked together at Collective Impact. Davis described the Mini Cooper as “essentially” Collective Impact’s vehicle, though DMV records list her as the primary owner, with Spingola on the registration as a secondary owner.

Spingola has three vehicles registered to the shared address with Davis, including two registered solely under his name: a 2020 Land Rover and a 2023 motorcycle.

Dream Keeper’s controversies

At a recent meeting of the Human Rights Commission, the group pointed out that it has helped increase Black homeownership, offered vital professional development services, and helped support more than 20 small businesses in the city. Additionally, Dream Keeper leaders say they have issued funding to more than 200 scholars for postsecondary education.

“There’s been a lot of learning,” Davis said at the Sept. 5 meeting.

But the Dream Keeper Initiative has also come under scrutiny multiple times this year. In February, city investigators found that a recipient of Dream Keeper funds, J&J Community Resource Center, spent at least $100,000 on cigars, booze, and motorcycle rentals. In July, The Standard found that many Dream Keeper community partners struggled to build out capacity as planned, resulting in millions of dollars left unspent.

Last month, the Chronicle discovered (opens in new tab) that an educational organization that received Dream Keeper Initiative funds had hired few teachers in San Francisco, and many of the jobs went to Oakland schools or nonprofits. On Thursday, the Chronicle reported (opens in new tab) that a city audit found a “litany” of problems with Human Rights Commission spending. The story also raised questions about the commission’s accounting practices.

Last week, Davis called for an audit of the initiative, stating that she wasn’t looking for any particular instance of wrongdoing. Instead, she said the program’s funds, operations, and performance should be reviewed.

City Controller Greg Wagner told The Standard he has received that request.