In June, a 21st century urban fairy tale went viral on social media. In a since-deleted blog (opens in new tab) post published by a community startup called Live Near Friend (opens in new tab)s (opens in new tab), a happy, healthy, stylishly dressed group of San Franciscans showcased their 12,610-square-foot, multi-unit home in Ashbury Heights, acquired in 2019 for $5.3 million.

Inside the wood-shingled compound with sweeping city views, the collective was living out a millennial fantasy, replete with eight interconnected apartments across two buildings, a shared garden, and a hot tub. Their co-living utopia was home to seven couples, 11 children, and two grandparents, with all the amenities that multigenerational living can afford: built-in child care, school carpools, endless social opportunities, and a tight-knit sense of community.

“We don’t get babysitters. … Here you’ve just got your monitor on and go upstairs and hang out with your friends,” Alex Baruch, a VP at wealth management group Fisher Investments, who lives in Unit 8, wrote on the blog. “To always know that I’ve got at least 1 to 6 friends that will be down to hang out or do whatever — that is pretty special.”

The friend group included a portfolio manager from Crosslink Capital, a managing partner from a real estate investment firm, and a jewelry designer whose earrings retail for as much as $6,000. (opens in new tab)

“We never thought we would purchase a home in San Francisco,” wrote William Noel, 41, a partner at the Elkhorn Group. “We invited a bunch of friends to come see the building — 16 people in all — to see if we could somehow pull it off.” Afterward, according to the blog, they ordered pizza and discussed whether they could transform it into their dream home. They concluded that, yes, they could.

Their story resonated with readers. “Love this,” tweeted Turner Novak (opens in new tab), a venture capitalist at Banana Capital. “It’s awesome having more than just your core nuclear family to lean on.” “Really cool,” responded Moses Kagan, (opens in new tab) president of Adaptive Realty, a real estate private equity firm.

Live Near Friends, the startup that published the “millennial commune” success story, promoted it as an exemplary model of co-living done right. The company, whose goal is to solve the “loneliness epidemic” by “making it easier to create friend enclaves,” was not involved in the planning, execution, or development of the Ashbury Heights property and is not affiliated with the residents, a spokesperson said.

Today, the company is making an effort to distance itself from the collective because of an uglier back-story: In order to make room for the stylized sectionals, artful group photos, and sunlit midcentury modern rooms on display in the blog, the Ashbury Heights crew evicted 13 low-income, elderly, and disabled long-term residents.

'It wasn't just an apartment building. It was a home for us all. ... I don't know how the new owners can live with themselves.'

Jesse Payne-Johnson, evicted from Unit 3

Employing the Ellis Act (opens in new tab) — a 1985 state law that gives landlords permission to evict tenants if the property is permanently removed from the rental market — the compound’s new owners forced long-term residents out of their homes and disbanded a community that former tenants say was already thriving in the building.

Many who were evicted signed nondisclosure agreements in exchange for cash settlements. Through court documents, interviews with former tenants and housing activists, and emails between tenants and public officials acquired through public records requests, The Standard was able to piece together the story of what happened when one group’s San Francisco housing dream came at the cost of another’s.

In 1977, at 36, Dave Dunham became the first tenant to live at the newly completed multi-unit building in Ashbury Heights. (The Standard is not revealing the address of the home in order to protect the current owners’ privacy.) Dunham’s three-bedroom, three-bath apartment boasted vaulted ceilings, a wood-burning fireplace, and a wet bar. His unit was subject to rent control; by 2018 — 42 years after he moved in — the rent had climbed to $2,400.99 per month, which housing activists who assisted him say was covered by his retirement payments.

Dunham, whose story was recounted by another tenant, watched generations of neighbors come and go. When Jesse Payne-Johnson moved into Unit 3 in 2015, Dunham playfully called him a “young ’un.” Payne-Johnson, 41, a partner at law firm Scale LLP, recalled this fondly, explaining that he chose the building for its tight-knit community. Unlike other residents, Payne-Johnson did not accept a settlement or sign an NDA, and was able to speak with The Standard directly. He said residents looked out for one another, hosted coffee catch-ups, and celebrated birthdays together.

The first time he met Carol DiBenedetto, 61, a climate strategist who had lived in Unit 2 since 2004, she invited him and the rest of the building’s residents to her annual Chinese New Year party. Payne-Johnson responded in kind, fetching groceries for neighbors with mobility issues and helping with small repairs. By 2019, he was paying $4,231 a month, according to rent board documents — one of the few tenants paying close to market rate.

DiBenedetto paid $2,470 a month for her two-bedroom, two-bath unit, while some of the elderly tenants paid nearly 70% below market value, according to the rent board. “It wasn’t just an apartment building. It was a home for us all,” Payne-Johnson said.

In 2018, the tenants of the Ashbury Heights building learned that Trinity Management, founded by the late Angelo Sangiacomo — one of San Francisco’s largest landlords, with a history (opens in new tab) of tenant evictions — had listed the building for sale at $6.3 million.

“Pictures do not do this property justice,” boasted the listing. “This property represents a true pride of ownership asset that will attract a high-end tenant and command top of the market rents.”

When the listing went live, panic swept through the building, Payne-Johnson remembers. “Residents were stressing out. People didn’t know what to do,” he said.

'We do not believe these "socially conscious" Millennials realize they'd be evicting long-time, protected, disabled, and rent-controlled tenants.'

Carol DiBenedetto in an email to her district supervisor

DiBenedetto was particularly determined to stay in her home, according to Payne-Johnson and housing activists who assisted her efforts to avoid eviction. (On the advice of her lawyers, DiBenedetto declined to comment for this story.) She sought advice from District 8 supervisor Rafael Mandelman and the Mission Economic Development Agency (MEDA), pleading with them to intercede on the tenants’ behalf.

“We are under the gun re: timing, if we are to save our building’s residents from eviction,” she wrote in an April 2019 email to Mandelman. “We urgently need to fast-track this process to prevent our rent-controlled building sell-out and eviction of long-term tenants to ‘market-rate buyers.’”

“The tenants were doing all the right things,” said Juan Diego Castro, the national partnerships director at MEDA, who consulted with DiBenedetto. “They were apprehensive but hopeful.”

In a city where the median home price hovers around $1.2 million and 65% of residents are renters, the power imbalance between landlords and renters is seismic. Between 2018 and 2024, more than 565 rent-controlled units were removed from the market under the Ellis Act, according to government records, and countless more were pushed out through quiet buyouts that shielded the stories from public view, according to housing attorneys and anti-eviction advocates. According to SF Rent Board data, 797 (opens in new tab)eviction notices were filed between March 2023 and Feb 2024, a total that includes some but not all evictions for nonpayment of rent.

While the Ashbury Heights renters’ circumstances were not unusual, Castro said, their mobilization was. DiBenedetto asked Mandelman via email about the Small Sites Program, (opens in new tab) designed to protect vulnerable tenants by converting rental units to permanent affordable housing. She also researched San Francisco’s Community Opportunity to Purchase Act (opens in new tab), which allows tenants the first chance to buy, before a property is offered to outside parties.

But the residents weren’t eligible for those programs. “It was very upsetting,” Mandelman told The Standard.

Soon, prospective buyers began arriving for viewings. “We put signs up in each unit that said, this is a community of people, some who have been here for decades. … We don’t think you should buy this building,” said Payne-Johnson. The hope was that buyers would realize who they were displacing and reevaluate.

“We do not believe these ‘socially conscious’ Millennials realize they’d be evicting long-time, protected, disabled, and rent-controlled tenants,” DiBenedetto emailed Mandelman again on April 2, 2019.

The signs didn’t change the buyers’ minds. In May 2019 (opens in new tab), Trinity signed the deeds over to an LLC created by the friend group, a transaction that was mentioned in the viral blog post. The purchase price of $5.35 million was nearly $1 million less than the list price, which was likely due to the inconvenience of seven out of eight apartments being occupied by renters, according to realtors who specialized in nearby home sales.

In June 2019, the new owners sent every tenant a softly worded notice by email and letter. “We are a group of eight couples who have known each other for years. … We purchased this building so that we could move into the units and live together in San Francisco (a city we’ve lived in and loved for 10+ years) to raise our families,” it read. “We are prepared and intend to remove the building from the rental market under the Ellis Act.” They said they would first offer voluntary buyouts.

Residents were in tears — anxious, panicked, some fearing homelessness. “It was a terrible day,” Payne-Johnson recalled of receiving the email.

The email from the new owners troubled Lisa Zahner, a Bay Area real estate agent who specializes in residential, multifamily, and investment properties, and who has no connection to the Ashbury Heights property. “I understand their desire to move into a building together, but the tenants have been there a long time, and it’s their home,” she said. “If you’re buying a building with tenants, you need to be comfortable having those tenants.”

Zahner said there’s been an uptick in San Francisco friend groups looking to buy homes together. It’s rare, “but not impossible,” to find a fully vacant multi-unit building, she conceded.

The Standard attempted to contact the owners of the Ashbury Heights building over several months via phone, email, and mail. Frasher Kempe, a Salesforce account executive who lives in Unit 6 with his family, told The Standard by phone that he was not “available to talk now or ever” before ending the call.

Brynn Noel, who lives in Unit 1 with her husband, Will, provided an email statement on behalf of the collective. “We are grateful that we were able to become homeowners in San Francisco and are proud of the community that we created,” she wrote. “We of course would have preferred to purchase a completely vacant building. We understand that not everyone agrees with the use of the Ellis Act and accept that. … We followed the law and approached the situation from a place of care and respect.”

Regarding specific questions from The Standard, Noel responded that the owners “do not feel that we are at liberty to have certain discussions due to legal restrictions.”

Facing high odds of eviction, the tenants found it increasingly difficult to stay positive. The new owners frequently came by and demanded access to the units, according to several sources. Once inside, they measured floors and doorways and loudly discussed paint colors, while their soon-to-be cast-out residents (many of whom had no savings or family safety net, according to Payne-Johnson) were forced to watch their homes reduced to square footage.

As the building’s very first tenant, Dunham found this especially hard, according to a housing advocate familiar with his situation. During his 43 years in the building, he’d spent hours painstakingly carving a design into a custom shelving unit. When the new owners saw his work, they sighed and said they’d “have to trash that garbage,” according to the advocate.

DiBenedetto lashed out at her supervisor, Mandelman, for his inability to stop the new owners’ actions. “I would like to tell you how incredibly disappointed I am that our Supervisor failed us,” she emailed Mandelman on June 20, 2019. “Your newsletter shows you enjoying Pride Parade festivities and ribbon-cutting ceremonies, but where is your priority for helping your residents when they need you?”

Every tenant refused the initial buyout offer, according to Payne-Johnson. But by August 2019 it was clear that eviction was unavoidable and some tenants began leaving. Some accepted San Francisco’s mandated relocation fee, which was around $11,600 (opens in new tab) based on residents’ age or disabilities, plus undisclosed cash settlements, according to sources familiar with the transactions. Experts say Ellis Act settlements often mirror buyout payments, which tend to range from $30,000 to $80,000 per person.

These payments, according to people familiar, were offered to discourage tenants over a certain age or with disabilities from lingering for another year, as was their right under the Ellis Act. The settlements came with strings — residents were forced to sign a non-disparagement agreement, which precluded them from sharing their experiences at any time in the future.

Some of the evictees moved in with friends. Others moved into below-market-rate apartments in the city or over the bridge in Marin. One relocated to Florida.

As the new owners began moving in that fall, the atmosphere between them and the leftover tenants went frigid.

Payne-Johnson chose the silent-treatment. “I overlapped with them for about eight months, and I never said a word to them,” he said. It was uncomfortable, he admitted, but there was too much tension to gloss over. “I refused to engage. … I didn’t even want to look at them.”

Karen Lee, a housing activist, said her friend DiBenedetto was traumatized by the experience. “Living with your evictors is … ugh,” Lee said. “You feel trapped in your home, trapped if you go out. Carol was furious that these young kids were creating a ‘housing utopia’… off the back of helpless, vulnerable people.”

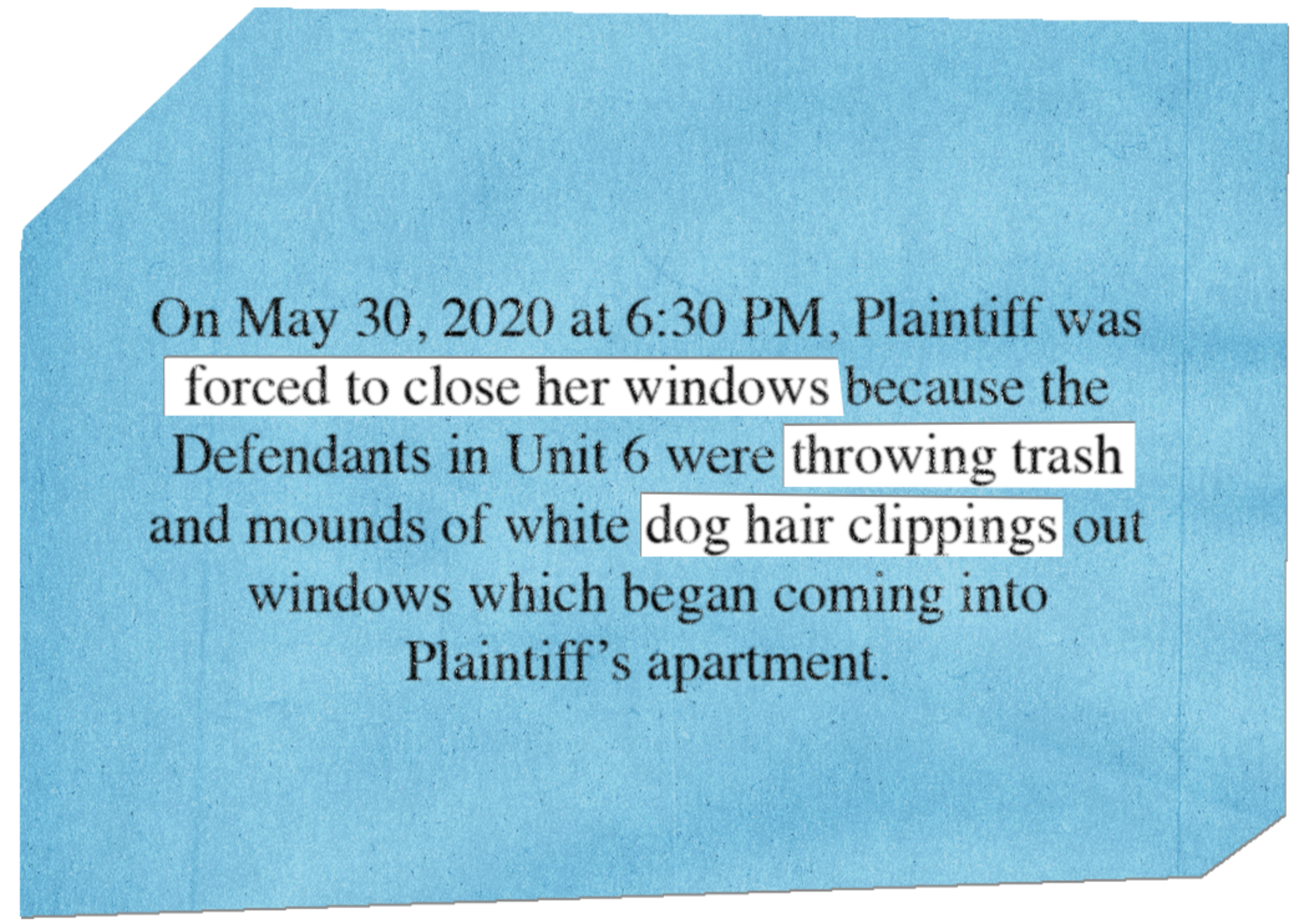

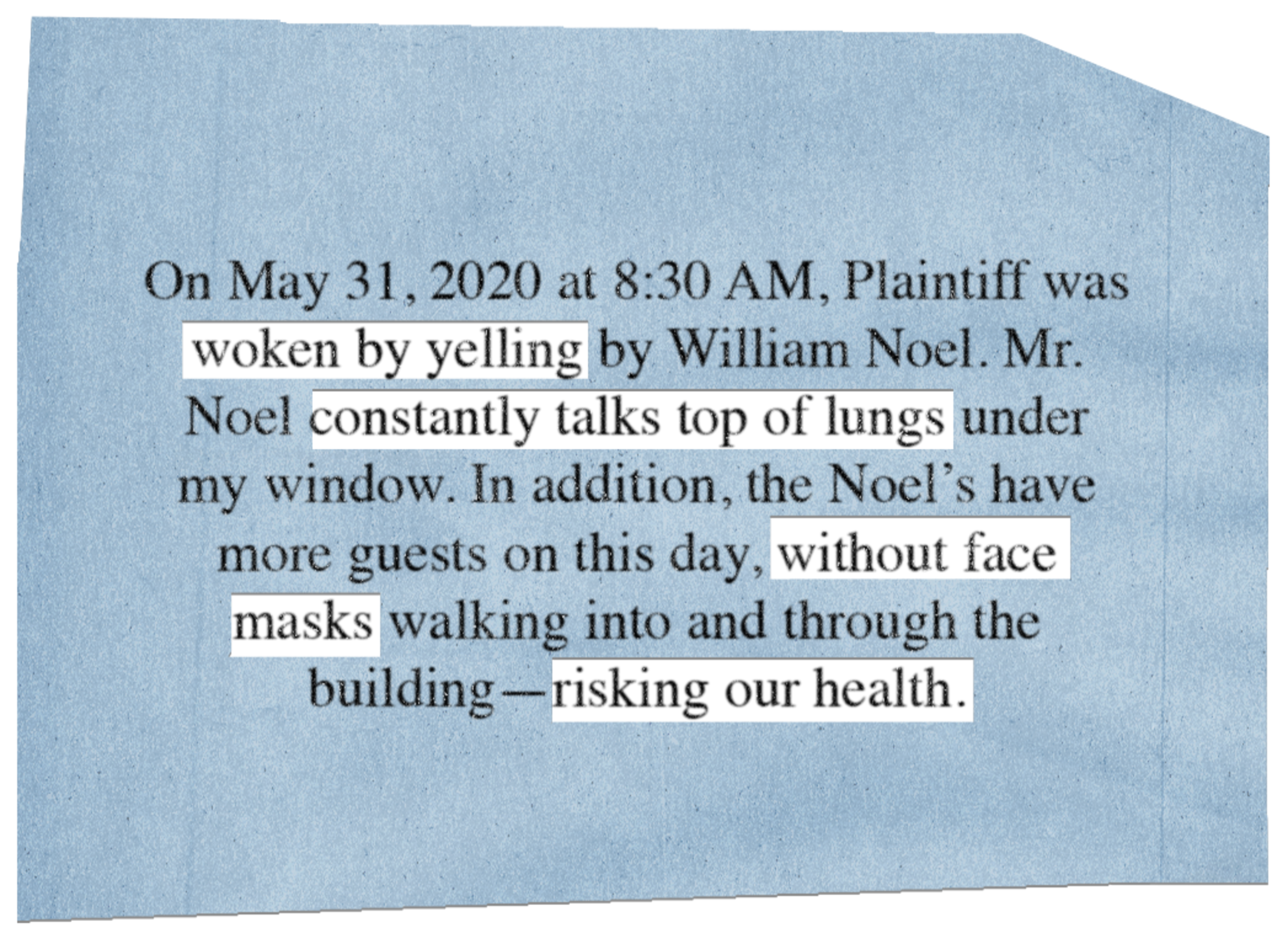

In a legal complaint filed in August 2020, DiBenedetto claimed she was repeatedly locked out of the garage and couldn’t access her accessible-parking placard once the new owners moved in. She wrote that delivery trucks blocked her garage entrance, week after week. She had to close her windows due to trash and “mounds of white dog-hair clippings” being thrown from the unit above hers, and she couldn’t focus on her work due to nonstop hammering and construction, she alleged in the complaint.

What she saw as chaos, the buyers described as progress. “[We] managed multiple contractors and lived through construction to transform the dated, dreary building,” Meredith Kempe, the interior designer who moved into Unit 6, wrote on Instagram (opens in new tab) last fall. “[It’s now] a thriving and fun family community.”

In January 2021, DiBenedetto and the owners came to a closed-doors agreement over her complaint, and the case was dismissed.

DiBenedetto and Payne-Johnson were the last tenants to leave in 2021. DiBenedetto moved in with a friend in the East Bay, and Payne-Johnson rented an apartment in the Castro. Dunham, now 84, left in early 2020, moving three miles north to an apartment in Western Addition. They put the past behind them and moved on.

Then the Live Near Friends blogpost published last summer.

“Nothing brings me more joy than having a house full of my people for kid dinner, happy hour, or a deck hang,” wrote Kempe in an Instagram post celebrating the blog. “I love helping people create homes that they’re proud of and want to share with the people in their lives.”

Unit 8 resident Baruch rejoiced in the Live Near Friends company post about “getting home every day and bumping into your best friends, and having your kids go off and play together. … I could leave tomorrow and leave my boys for 3 days and the community would absorb them. I don’t need to get clothes out, or tell them where the toothbrush is. It’s so much simplicity.”

For the former tenants, the post opened up old wounds. Friends and acquaintances called and emailed: Had they seen the post?

“I’m disgusted. I don’t know how they live with themselves,” said Payne-Johnson. “What are they going to tell their kids when they find out what they did to us?”

DiBenedetto’s friend Lee was appalled when she saw the article. “They were gloating about their perfect community, that they created a magical multigenerational space,” she said. “Carol hasn’t been able to look at it. … It’s still too raw.” It made them both nauseated, she added. “Nowhere do they say that their home was at the expense of [13] other people. That’s what colonists did to Native Americans.”

When Live Near Friends was informed by The Standard of the evictions and stories of the former tenants, it removed the blogpost from its website. “We do not support Ellis Act evictions, and we do not help people do them,” a spokesperson said. “This happened years before our company existed. We solely feature properties that have multiple vacant units.”

In somewhat of a twist, two of the new owners have since left the compound. The couple in Unit 4 decided to sell in 2023. “A unit in our communal apartment building is up for sale. The vibe of this one is incredible,” Will Noel, from Unit 1, posted publicly on Facebook. (opens in new tab) “We would LOVE to have another close friend or friend of a friend move in. Please share.” The apartment sold for $1.4 million; its previous owners purchased a $3.1 million, four-bedroom, 2.5-bath home in San Rafael, according to public records.

In late 2024, the couple in DiBenedetto’s former apartment sold their unit for $1.5 million and relocated to a $2.7 million home in Noe Valley.

An earlier version of this story included photographs of the building’s owners and their families by photographer Hannah Franco. After receiving permission from Franco to license the images, The Standard learned that they were owned by Live Near Friends, not Franco. We regret the error.