Two Oakland police officers squeezed behind the bar of The Lodge, a saloon on Piedmont Avenue, as if looking for hidden drugs or guns.

As late-afternoon customers watched — one filming the scene with a cellphone — a bearded officer shined his flashlight into liquor bottles, holding them up to the light as he kept an eye on the drinkers watching him.

“We’re just curious, what are you looking for?” asked a woman sitting at the bar.

“It’s a bar check for ABC,” he said, a smirk crossing his face, referring to the California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control. “We’re OPD, so we do bar checks and make sure the licenses are good and make sure they’re not serving alcohol that has bugs in it.”

“Oh, OK,” she replied.

Uniformed cops spending their time checking liquor bottles for fruit flies, in a city where the police force is 30% below its proper staffing level (opens in new tab)? No wonder those bar patrons were surprised on that Wednesday in May 2023.

What they witnessed was an operation of the Alcohol Beverage Action Team, a 20-year-old unit of the Oakland Police Department that inspects and enforces rules at corner stores and bars. Those businesses pay a special fee to fund the six-person team, which was conceived as a way to combat a range of urban ills, from littering to prostitution. Known colloquially as the “party police,” the unit operates under the long-disputed “broken windows” theory, which claims that minor unaddressed issues like garbage and graffiti lead to more serious crime.

It is a rare situation in the state, and one that bar owners argue imposes significant costs on them without improving public safety.

A Standard review of five years of ABAT inspections shows that the team has identified underage liquor sales and seized illegal drugs and weapons at many corner liquor stores. But bars in the same period were fined only for minor infractions, such as missing signage, graffiti, or failure to pay city business taxes.

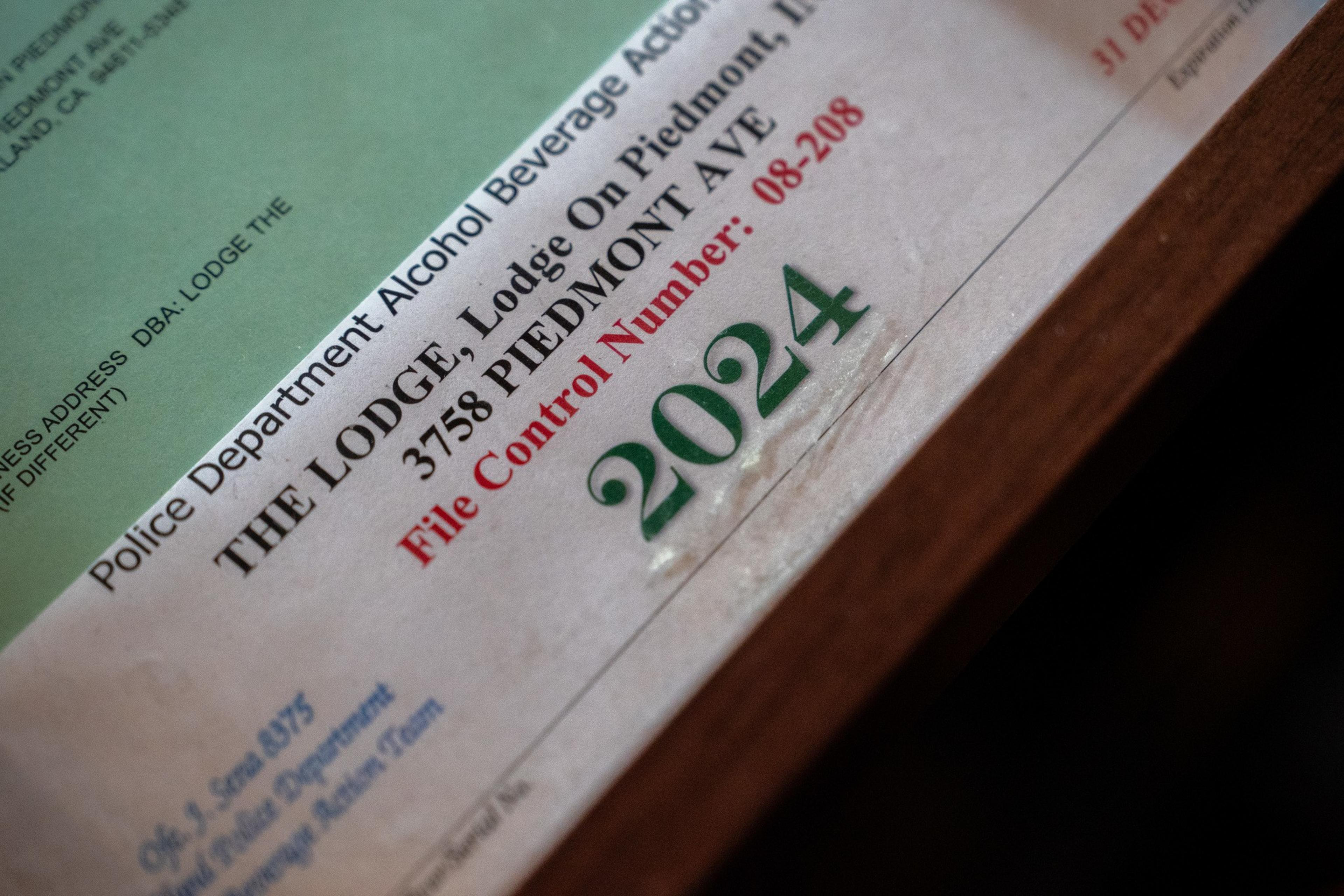

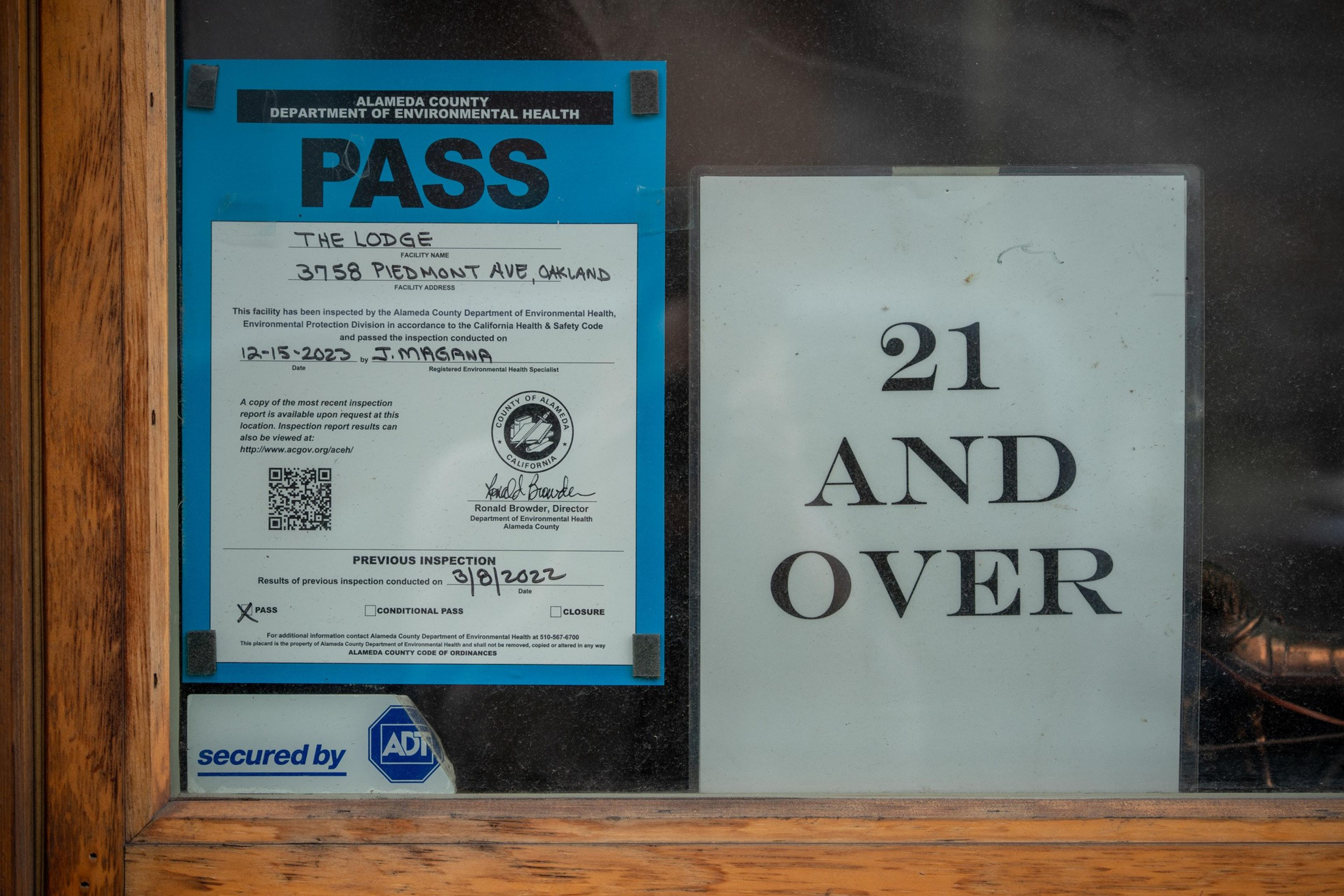

At The Lodge, the officers issued citations for not posting signs about human trafficking and alcohol health warnings, according to records. To address the violations, owner Lexi Filipello would have to pay a $200 reinspection fee. The bigger-ticket item was her failure to pay the bar’s annual $1,500 ABAT fee — the one paying for the inspection.

Like other bars, The Lodge is subject to regular inspections by the county public health department to maintain the health code and the state’s Alcoholic Beverage Control for liquor laws. Like many of her peers, Filipello has trouble understanding how ABAT’s inspections are worth the money she pays: “Every time they come in, it makes me wonder, why are they here enforcing this?”

A vogue for ‘broken windows’ policing

Back in 1993 the now largely debunked (opens in new tab) “broken windows” theory was sweeping the nation.

That year, Oakland embraced the theory by focusing on what it saw as increased crime outside of alcohol-related businesses. “Public nuisance problems, such as litter, loitering, prostitution, drug transactions, public urination and public drunkenness, are strongly associated with the operation of alcoholic beverage sale establishments,” read an ordinance announcing the creation of the ABAT team and new regulations that allowed the city to monitor specific alcohol-related businesses.

A cohort of corner stores sued but lost their case, and the law went into effect.

Elihu Harris, Oakland’s mayor at the time, told The Standard the law was intended to focus on the flatlands, where most corner stores were located and crime rates were highest. In many cases, he said, crimes occurred outside of corner liquor stores.

“They felt these were places where crime, drugs, alcoholism — all these things were connected,” he said of city leaders at the time. “It was more the liquor stores than anything else. I don’t think the bars were a focus.”

But bars were included in the law’s scope nonetheless. The ABAT team was tasked with looking out for nuisances and instructing business owners on their liability. In turn, the newly extra-regulated businesses were required to pay a $600 annual fee to fund the police unit — slightly less, in inflation-adjusted terms, than the current fee.

In addition to monitoring bars and corner stores, the law gave ABAT enforcement power over restaurants that serve liquor along what were considered high-crime corridors: almost all of San Pablo Avenue, MacArthur Boulevard, and Foothill Boulevard.

The ABAT team has two full-time officers, three civilian employees, and a deputy city attorney, and it generates annual revenue of approximately $1 million from fees collected. The unit visits the roughly 450 businesses — of which 66 are bars — on its list at random, handing out a compliance certificate with a checklist. Infractions can include expired products, litter, failure to have permits for special events, excessive signage, failure to post required signage, proper lighting, graffiti — as well as, of course, failure to pay the ABAT fee.

A 2011 annual report (opens in new tab) about the team boasted that it not only paid for itself but brought in revenue to the city by reminding businesses it inspected to pay their local taxes.

OPD officials maintain that everything ABAT does falls within its legal mandate.

“Officers have broad authority when conducting inspections,” a department representative said in a statement.

Why it needs that broad authority is less clear. Oakland’s bars tend to be heavily clustered in neighborhoods with low rates of violent crime, such as Rockridge, Temescal, and Piedmont, while more dangerous areas, such as Fruitvale and East Oakland, have relatively few.

While the 1993 law justified the need for ABAT as a deterrent to nuisance crimes, the OPD said it has no up-to-date analysis of how much crime is happening in correlation to bars. The department also said it has no data on whether crime corridors written into the law still have those issues, or why a number of restaurants along those thoroughfares are not part of the program.

The Standard’s review of ABAT activities found that the team selectively enforces the rules and often misses large swaths of the city’s alcohol-related establishments.

Which establishments are not subject to the program appears arbitrary, too. Brewpubs are not part of ABAT at all, nor are most restaurants that serve liquor.

Asked why breweries don’t fall under ABAT, the OPD representative could not offer an explanation. “We will look into the issue with the relevant city departments,” the statement said.

Since 2019, the most common ABAT citations at bars have been for failing to exhibit required signage and failing to pay business tax. A minority of inspections were flagged for dirty drink dispensers, a lack of beer tap labels, or failure to have a live music license. None of the bars sold alcohol to underage decoys.

‘I don’t really know what they do’

The Avenue, with its cave-like interior, caters to punks, aging goths, biker wannabes, and anyone else who likes to drink. The bar’s decades-long presence on Telegraph Avenue in Temescal has made it a neighborhood anchor.

Curtis Howard has owned The Avenue since before ABAT was instituted. And the unit has annoyed and perplexed him since.

Many of his interactions with ABAT have felt arbitrary and unnecessary, he said, and the unit’s educational programs were clearly designed for corner store owners, not bars. He recalled being chastised during one class for not recognizing a disguised crack pipe sold at some corner stores. When the instructor learned Howard was a bar owner, he apologized.

“We just have to pay them every year. I don’t really know what they do,” said Howard. “I just know if we don’t pay them, we get in trouble.”

Every bar owner contacted by The Standard expressed confusion about ABAT’s purpose. Many said the unit’s main function is to make their lives harder, when doing business as a bar is already tough enough.

“It’s just basically a tax on saloons and corner stores to fund OPD,” said one downtown bar owner.

Kevin Pelgone, who opened one of West Oakland’s few bars, 7th West, in 2019, said it’s been an “uphill battle since the pandemic,” and he’s seen many bars close. “We are all under the fear of closing just because of the macro economics.”

Some bar owners — several of whom requested anonymity, citing fear of reprisals — described their belief that ABAT uses an implied threat of additional inspections for unrelated violations to compel businesses to pay the annual fee. They said the unit intentionally conducts inspections during peak business hours to maximize the disruption — and thus the incentive to cooperate.

One owner described opening his door to a uniformed officer, who handed him a piece of paper explaining how to pay the fee. The owner declined to hand over a check on the spot. A short while later, he said, five uniformed officers came back and performed what they described as a “health inspection.”

He paid the fee.

Cops as tax collectors

In August 2024, ABAT’s team walked into State Market Liquor in West Oakland and hit the jackpot: illegal flavored tobacco for sale, narcotics, and an illegal gun.

Oakland Councilman Ken Houston says raids like that make the city safer. “It’s a unit that’s desperately needed in Oakland,” he said.

But even if ABAT’s policing of liquor stores has a legitimate effect on some types of crime, there’s a significant downside in the practice of using cops to collect money from businesses, experts say. There’s a reason, they note, that few if any other California police departments do so.

Michael Makowsky, an economist at Clemson University in South Carolina who studies policing, says the practice runs the risk of turning police into tax collectors and alienating the community by making cops appear to be focused on matters other than public safety.

“It is unfortunate that a police officer, during a time of heightened concern over violent crime and retail theft, would be an unwelcome visitor at a local business for fear that they are solely there to extract thousands of dollars in fines and fees,” he said. “There are few methods of revenue generation less efficient than law enforcement.”

Bar owners say that while the ABAT team is busy collecting fees and making inspections, regular OPD officers are often absent when needed. A Rockridge bar owner said she has been visited by ABAT regularly, but the police failed to respond on five separate occasions when the bar was robbed.

Owners also recall that during the pandemic, when Oakland had some of the country’s strictest shutdown rules for bars and restaurants, ABAT all but halted inspections — but continued to assess its usual fees.

Filipello at the Lodge says the program makes business owners feel like they are the city’s enemy, not those helping to make the city thrive.

“I’m not doing anything illegal,” she said, “but they create this dynamic that makes you feel like the scum of the earth.”