Want the latest Bay Area sports news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here to receive regular email newsletters, including “The Dime.”

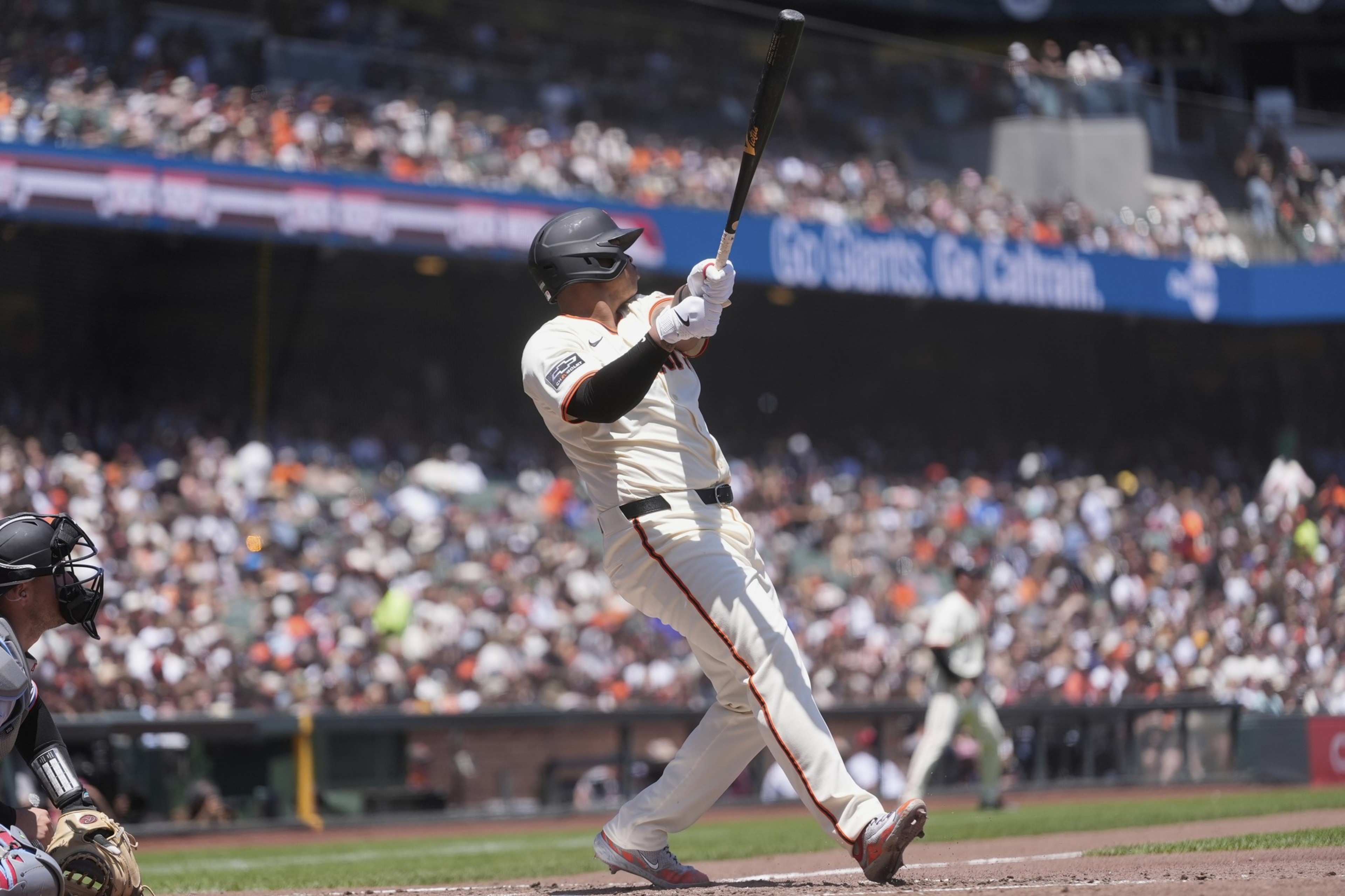

As a hitter who crushed baseballs to all fields, Buster Posey was so committed to going the opposite way that sometimes he’d try to hit pitches into the first-base dugout.

Not that Posey was aiming to drill anybody, mind you. It was simply a method he used if he needed to get his timing back in sync, to force him to hit to right field on certain pitches. He says now it was about “overcorrecting” any issue with his swing.

“It mentally slowed me down,” Posey said. “A little trick to my brain.”

Now the Giants’ president of baseball operations, Posey is overseeing a team that has struggled to generate runs for much of the season, the recent surge of winning four of five notwithstanding. When the offense is at its best, hitters tend to correctly do the little things by getting ’em on, getting ’em over, and getting ’em in.

And letting the ball travel.

That was a Posey speciality: letting the ball travel in the strike zone or letting the ball get deep or staying back on the ball or staying behind the ball or staying inside the ball — all catchphrases that are code for waiting that extra millisecond before swinging.

Technically, that makes it easier to use the whole field and lessens the chances of becoming pull-happy or lunging early or rolling over a weak grounder.

In the Giants’ clubhouse, batting cage, and hitters’ meetings, using the whole field repeatedly is emphasized. Rafael Devers and some others begin their batting practice sessions by spraying the ball to the opposite side, sometimes powering up, in a bid to replicate the practice in games if given the opportunity.

In Sunday’s 6-2 win over the A’s in West Sacramento, Luis Matos provided a key moment with a two-out, bases-loaded double to right-center, an excellent piece of opposite-field hitting. During the recent five-game upswing, the team’s situational success has ticked up; Willy Adames continued to show promise in the wake of his first-half funk and went 8-for-15 with three extra-base hits and eight RBIs.

When things go south for the Giants’ offense — including the 16-game stretch from mid-May to early June without scoring more than four runs, and the recent 4-12 nosedive — the basic fundamentals of hitting tend to be lacking, including an all-fields approach.

Whether it’s on display in the next week could figure into how the Giants fare against the Phillies and Dodgers. After they went 5-5 on a three-city trip opposing only sub-par teams, the offense gets a big test with two division leaders in town ahead of the All-Star break.

“You’ve always got to have it in your pocket, because pitchers are really good these days,” said Wilmer Flores, who has used opposite-field hitting to generate many of his team-leading 55 RBIs. “When the situation calls for it, say, man on third base, less than two outs, and the pitcher’s just throwing pitches away, away, away, and the only chance you have is going the other way, that’s when it really helps you. Same thing with man on second, I just want to let the ball get deeper and hit something hard to the middle of the field.

“I think analytics don’t always like that approach, but it’s nice when you do it, and everybody gets happy when you do it.”

Flores is a pull hitter by nature, but when the situation calls to push the ball the other way, he has succeeded. It’s not about exit velocity for Flores — he’s in the 2nd percentile among MLB hitters — it’s simply about hitting ’em where they ain’t.

That hasn’t been the case for Jung Hoo Lee, who supposedly is an all-field hitter. However, his 47.8% pull rate is highest on the team among regulars, and he has gone to the opposite field just 24.6% of the time, lowest on the team among regulars.

In a much smaller sample size, Devers went through a stretch in which he seemed lost with 16 strikeouts over 24 at-bats in six games. Once Devers arrived in a trade with Boston, manager Bob Melvin spoke glowingly about how well he lets the ball travel. However, through 71 at-bats, Devers has pulled the ball far more (44.4%) than he’s gone the other way (22.2%).

Not surprisingly, Heliot Ramos and Matt Chapman, who returned from the injured list over the weekend, are among the best at using all fields, hitting the other way at least 30% of the time. On the other hand, struggling second baseman Tyler Fitzgerald is in that range, too, which shows opposite-field hitting doesn’t automatically lead to success.

“I think all the best hitters use the whole field,” Chapman said. “That allows your mechanics to be better because you’re letting the ball travel, you’re under control. The opposite of that is when you’re rushed and fly open and come around the baseball. There’s a lot more hits when you’re staying inside the baseball, you’re staying short, and it gives you the opportunity to handle some of the off-speed pitches, too.

“Now, some of it is more of a mindset than actually trying to manipulate the ball and force it over there. It’s about letting the ball travel, staying back behind the baseball and being OK hitting it the other way, but you also want the ability to pull the baseball if you need to.”

Indeed. One of Flores’ most memorable at-bats came last month against Cleveland when he pulled a pinch double down the left-field line, driving in two runs in a 2-1 win. Flores admitted that wasn’t his plan at all.

“I was trying to go up the middle,” he said. “It was a breaking ball. I saw a lot of fastballs where I was late. I got a breaking ball in the zone, and I was on it.”

In other words, good things can happen when a hitter doesn’t try to pull the ball 500 feet. The Giants, who rank 16th in the majors in hitting balls to the opposite direction, don’t have a power-hitting team; they’re 24th in homers. Hence, it’s smart baseball to go the other way, line balls to the gaps, and generate rallies with smart approaches, especially at hitter-not-so-friendly Oracle Park, where most hard-hit fly balls go to die.

It’s tougher than it sounds, of course. With today’s pitchers’ elite velocity, the reaction time for hitters is less than ever. The different mixes of pitchers makes it even tougher.

Hitting coach Pat Burrell said Flores’ ability to spray the ball is a “gift” that takes a “massive amount of adjustability.” Not everyone has that gift, so it’s a never-ending process to work on it.

“We’ve got 13 guys,” Burrell said of his position players. “They all interpret information differently. They all see pitches differently. They all have different strengths. All of it applies, whether we let pitches get deep with better decisions or whether we decide this is a pitcher we have to catch out front.”

There’s far more instruction with technology than in years past. It’s not “just go up there and hit the other way.” It’s easier to break down the approach, timing, and contact point including with modern stats. For example, the metric “Intercept Y (vs. Batter)” measures the point where the bat meets the ball in relation to the front edge of the plate and batter’s center of mass (midway between the hips).

It’s still hard. It’s still a challenge. Even for the best hitters in the world.

Lee was hitting .312 with an .871 OPS on May 6. Since then, he’s at .193 with a .586 OPS. The South Korean who grew up idolizing Ichiro Suzuki, a master at hitting to all fields, said he works hard on taking pitches the other way — “I really want to keep it simple, trying to send the ball over to left-center and hope to get the results” — but pitchers are making it difficult.

“It might be stamina. It might be the opposite team putting in some data on how I play,” Lee said. “It’s something I’ve got to get through right now.”

Likewise, Devers is bidding to regain his opposite-field approach. His 2025 spray chart shows a near balance of homers to the left side as the right side, which is remarkable considering his open batting stance. With his front foot nearly touching the back of the batter’s box, his open stance angle is 62 degrees, largest in the majors, according to Statcast.

By comparison, Lee is 41 degrees open, ranking seventh in the majors, while Adames and Mike Yastrzemski are a mere one degree. Also, Devers doesn’t exactly have a short swing enabling him to go the other way. It’s relatively long, 7.6 feet in length. Adames’ 8.1 is longest on the team and sixth-longest in the majors.

More important is the contact itself. Where, how much barrel, and (unless you’re Flores) how hard. Devers, known to have an excellent eye (his walk percentage is in the 98th percentile), still ranks in the 97th percentile in hard-hit rate and 94th in exit velocity.

Devers said he’s at his best when using all fields and admits he’s still seeking that oppo stroke: “I know that I’m a very good hitter when I swing the opposite way, let the ball travel. They’re pitching me with high fastballs, and I know I need to make adjustments.”

Posey said quality opposite-field hitting is an attribute of any good offense, and an all-fields approach can put a batter in a better position to flourish.

“To me, the biggest thing when you’re thinking about letting the ball travel, seeing it a little bit longer, is it gives you a split-second more to make a decision. The pitch sometimes might just dictate it, but I just believe you’re in a better position to hit if you’re thinking that way.

“The counterintuitive part to all of that, in my opinion, is you’ve got to be thinking swing every single pitch. It can’t be, ‘Hey, I’m going to see this pitch deep, and I might swing and I might not.’”

One of the best opposite-field hitters in franchise history was the great Willie Mays, who quickly learned at Candlestick Park that hard-hit flies to left field would be pulled down by the wind, so he targeted right-center because of the jet stream and made all kinds of history.

When Melvin played for the Giants in the late 1980s, he asked Mays how he hit so many homers at Candlestick with the crazy wind patterns.

“He looked at me and goes, ‘Well, when the wind blows in from left, I hit ’em out to right.’ He showed that perfect inside-out swing where he just let the ball travel, stayed inside it and hit it out to right field, with power. That’s as much coaching as ever I got on that subject.”