A San Francisco planning commissioner was warned more than a decade ago that she risked a conflict of interest if she continued to vote on projects involving her former employer, a document obtained by The Standard shows.

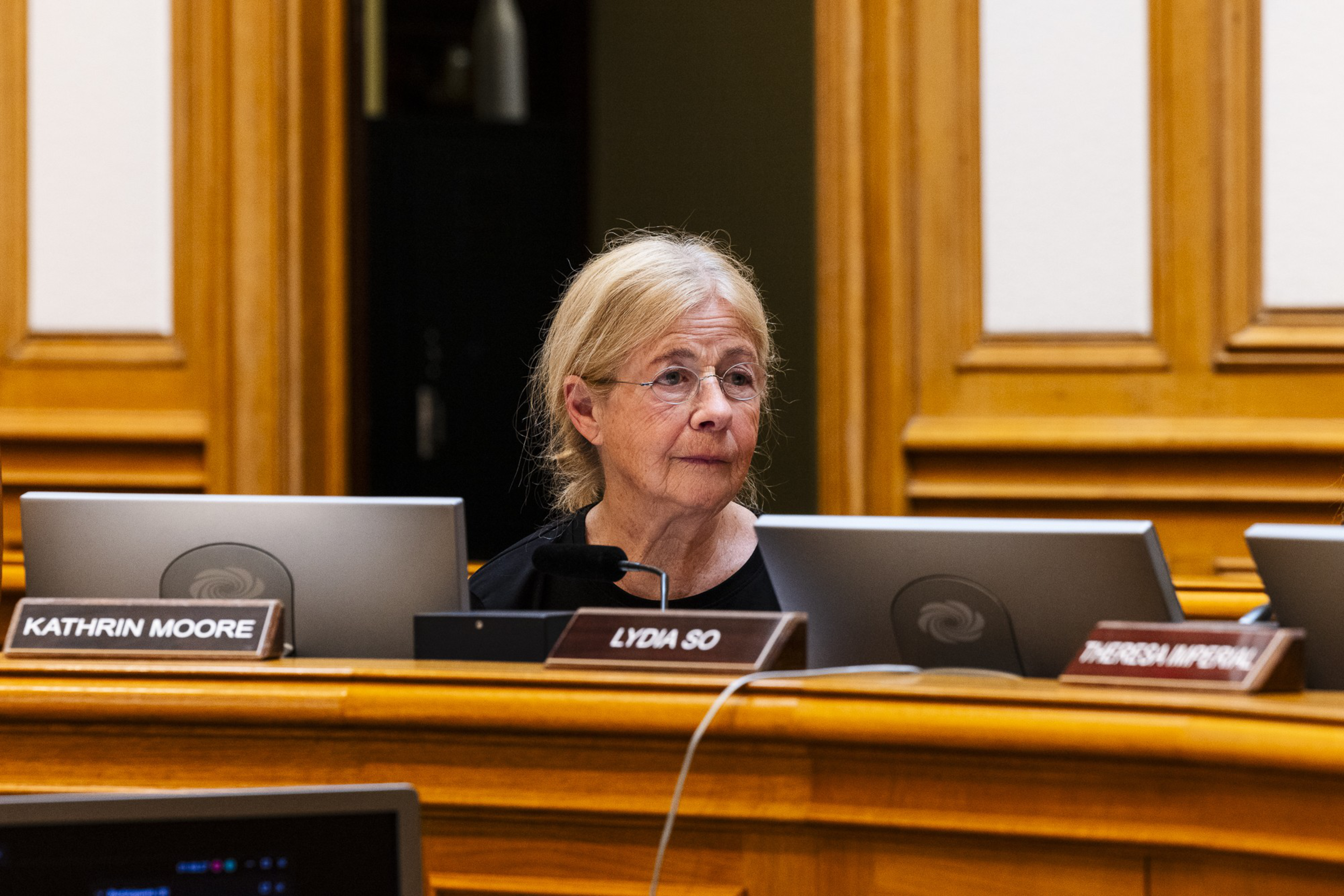

In spite of that warning, commissioner Kathrin Moore voted to approve multiple projects linked to Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (opens in new tab), the internationally renowned architecture firm, from which she retired as an associate partner in 1999. All the while, Moore continued to receive annual $15,000 retirement payments from the firm, known as SOM.

In response to an investigation into her conduct by The Standard, Moore said in a statement Monday that she would no longer vote on projects involving SOM.

“To remove even the appearance of any impropriety regarding my actions going forward, I will recuse myself from participating in any decisions relating to any project in which SOM is involved,” she wrote.

Moore, who was first appointed to the Planning Commission in 2006 and now serves as its vice president, approved the SOM projects even after being told in 2012 by the city attorney’s office that her votes could breach city and state ethics rules because of her financial interest in the company. In a four-page memo from April of that year, Andrew Shen, a deputy city attorney at the time, said he was writing to “confirm our prior advice” about potential conflicts of interest related to decisions Moore made regarding SOM in her capacity as a city official.

Shen’s memo outlined examples under which Moore’s decisions involving SOM could qualify as conflicts of interest. Those situations included voting on projects that would have “material financial effect” on the firm or involved individuals with whom Moore might have a “personal, business or professional relationship.”

The city attorney’s office also noted that Moore’s fixed retirement payments from SOM qualified as a financial interest under a state ethics law’s definition of income.

The seven-member planning commission, one of the city’s most powerful boards, votes on development projects and advises the mayor and Board of Supervisors on land use and transportation matters.

City officials, including planning commissioners, are prohibited (opens in new tab) from making government decisions involving an entity from which they have received $500 or more in income over the previous year. Commissioners regularly recuse themselves (opens in new tab) from votes, even if there is merely the appearance of a conflict.

The Standard previously reported that Moore voted to advance two SOM projects in San Francisco, a Buddhist temple on 1750 Van Ness Ave (opens in new tab), approved in 2021, and a building at 520 Sansome St./447 Battery, which is still pending before the commission. In response to The Standard’s reporting, the Planning Commission’s president, Lydia So, called for an investigation into Moore’s votes.

Since then, The Standard has discovered at least three more SOM projects that Moore voted to approve: 350 Mission (opens in new tab) in 2011; India Basin (opens in new tab) in 2018; and 98 Franklin (opens in new tab) in 2023.

In at least two instances, Moore recused herself from projects involving SOM: the Moscone Center expansion (opens in new tab) in 2014 and One Steuart Lane (opens in new tab) in 2015.

“I worked for SOM for a long period of time, almost three decades, and have an ongoing relationship with the firm,” Moore said during a vote for One Steuart Lane.

It’s unclear why Moore recused herself on certain projects but not others. Moore said in her statement that she believed she could vote on matters related to the architecture firm as long as she disclosed her relationship with the company.

“I have tried to consistently make that disclosure but it appears sometimes I neglected to do so,” she wrote. “Since I have been on the Planning Commission I have voted for and voted against projects in which SOM has been involved. I have sometimes praised and sometimes criticized projects in which SOM has been involved. I have never been influenced by anything other than the merits of each project, and I certainly have never been influenced by the fixed retirement payments I receive — payments which would never go up or down based on how I voted on a project.”

In a statement, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill spokesperson Ana Cuadra said Moore’s retirement payments are not connected to her activities at the planning commission.

“As a private-sector firm, it was our expectation that required disclosures, recusals, or potential conflicts of interest by the Commissioner were appropriately resolved with the City,” Cuadra wrote.

The 2012 memo didn’t explain what legal advice had previously been given to Moore. Jen Kwart, spokesperson for the city attorney’s office, said the office does not disclose privileged conversations, which are often provided to clients verbally. Kwart said it is up to officials to ask for an analysis by the city attorney or the SF Ethics Commission regarding decisions that may pose a conflict of interest.

The memo referenced a claim by Moore that she had previously been advised by the city attorney’s office that she was not required to report the SOM retirement payments on her annual disclosure forms.

“This office does not have any record of that advice,” Shen wrote. Moore began reporting her retirement payments on annual disclosure forms in 2012.

Sean McMorris, an ethics expert at the nonprofit California Common Cause, said rules prohibiting conflicts of interest exist “to prevent decisions based on real or perceived self-interest over the people’s interest.”

“When in doubt, a public official should seek advice from counsel, which it appears the commissioner did at some point, but perhaps did not heed entirely,” McMorris said. “On matters of conflict of interest, it is best to operate out of an abundance of caution than engage in action that could diminish the public’s trust.”

Moore was first appointed to the Planning Commission by former Board of Supervisors President Aaron Peskin and was most recently reappointed by Supervisor Shamann Walton. Her term ends in July 2026.

Walton’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Three of the planning commissioners are appointed by the board president, a role currently held by Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, while the mayor chooses the remaining four.