This column originally ran in the Off Menu newsletter, where you’ll find restaurant news, gossip, tips, and hot takes every week. To sign up, visit the Standard’s newsletter page and select Off Menu.

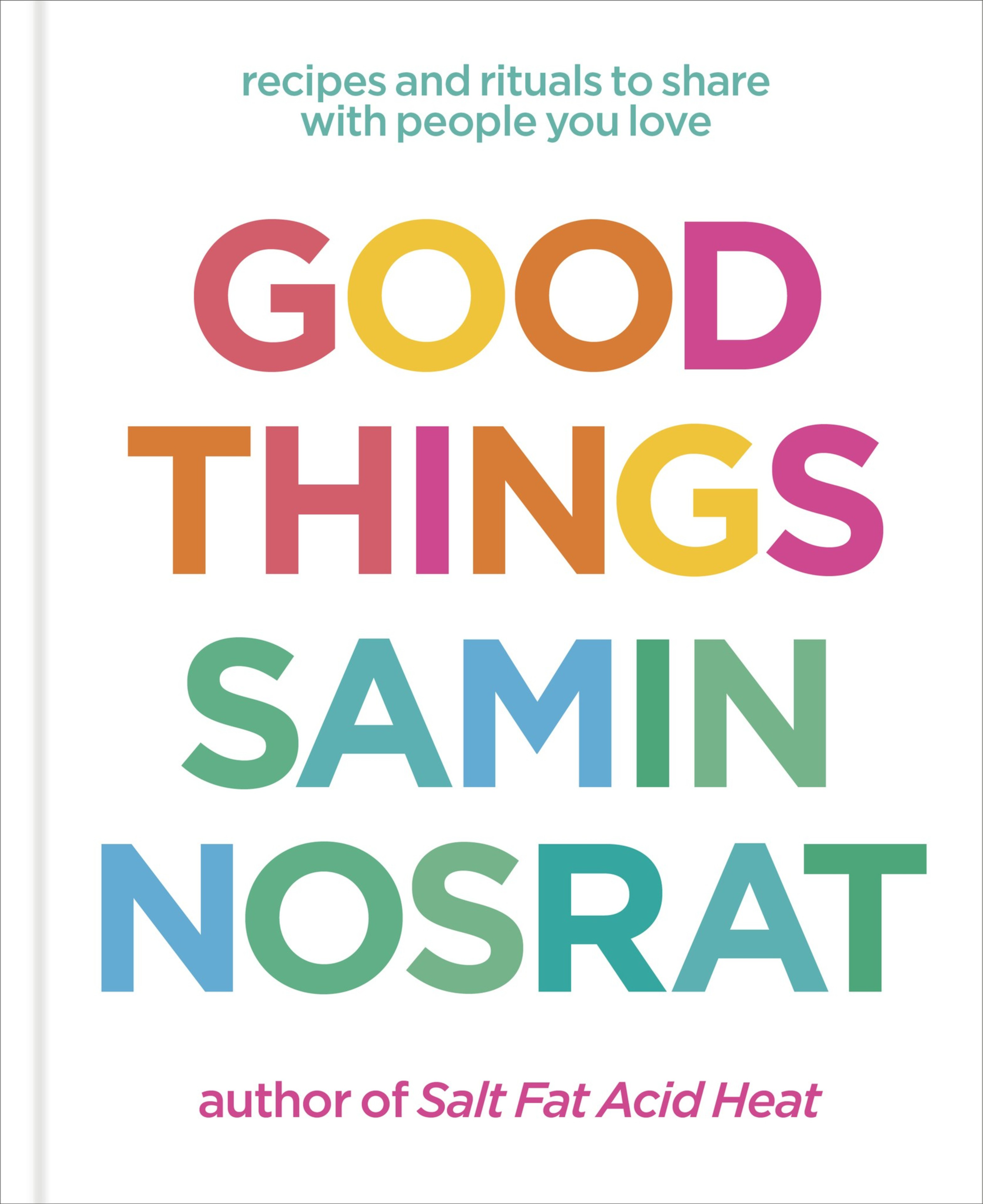

After eight long years, Samin Nosrat, the Oakland-based, Iranian American author of the breakout cookbook and Netflix show “Salt Fat Acid Heat,” has a follow-up. At the risk of irritating Martha Stewart, the new cookbook, which comes out Sept. 16, is titled “Good Things.”

To celebrate, 1,600 people have bought tickets to see Nosrat in conversation with “Song Exploder” podcast host Hrishikesh Hirway on Sept. 13 at the Sydney Goldstein Theater. It says even more about Samin fever that City Arts & Lectures added a second show Sept. 12 (opens in new tab). (I’m honored to be providing an onstage introduction, so please come!) “We don’t often add a second night,” said Kate Goldstein-Breyer, the co-executive director. “But we also did with Ezra Klein and Ta-Nehisi Coates.”

The fact that Nosrat is in the company of big-league talk-circuit personalities is both bonkers and makes complete sense. Though she’s happy to expound on the cabbage-slaw aha moment that led her to write her second cookbook, her identity has far transcended her status as a short-lived Chez Panisse cook.

At this point, she has evolved into an (often reluctant) public intellectual — someone people would really like to have over for dinner. Her new cookbook is littered with philosophical sayings. She quotes Audre Lorde (“There are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt”) and throws in her own Buddhist-tinged proverbs (“Good cooking is about being completely present as an experience unfolds”).

Nosrat’s rise to fame didn’t come solely because she taught us to let go of recipes as road maps and instead rely on the principles of taste. Most critically, she knows that cooking isn’t just about technique. She’s here to proselytize connection.

You sold out City Arts so quickly that they booked another night. How does that feel?

I remember [attending] my first City Arts talk. It was around ’98, Joyce Carol Oates. As a young person, I could go for like $20 and be in the same room as these authors and culture makers that I loved. I was totally the person who would think of a question and raise my hand and then stand in the line and have the book signed. So the privilege of being on that stage is not lost on me.

Is there a question you dread being asked?

Not so much anymore. But I had a really complicated relationship with my dad, who I was estranged from. So for my last book tour, I sort of lived in fear of somebody asking about that — or that my dad would show up. But now he’s dead, so that can’t happen. Plus, I’ve worked through a lot of the shame. I don't feel in danger anymore.

What inspired the title of your new book?

The working title was “Happy Cooking and Eating,” which was how I sign books to people. It’s like my wish for them. But then I realized that there’s a projection of me as a very joyful sort of person — always delighting so much in cooking and eating, which is not untrue — it’s just not the wholeness of who I am. I’m also a deeply depressed person and sometimes grumpy, and I didn’t want to use a title where this sense of me was perpetuated. I didn’t want “happy” to necessarily be the thing associated with my name.

So how did “Good Things” come to be the title?

It came from a Raymond Carver short story called “A Small, Good Thing” that I read over the pandemic. It’s very sad. In it, the parents have suffered the loss of their child and are in a deep state of grief, and they have this interaction with a baker who’s trying to care for them. He’s pulling rolls out of the oven and says, “Sit down, sit down, you need to eat something. Eating is a small good thing in a time like this.”

But then I realized if we called it “Small, Good Things,” it would sound like tapas recipes. So I was like, “How about just ‘Good Things?” Which sort of sums it up, you know? I realize Martha Stewart kind of has “Good Things” on wrap, but it just felt right.

My favorite part of the book is your essay on the importance of the ritual of a Monday-night dinner you have with friends. You call it “holy.” Are you still doing it?

Yes, it’s now big enough and stable enough that even when I leave for my tour, it will continue without me. And then it will be there when I get back. It’s so nice. In fact, we’re getting together tonight.

What are you having for dinner?

Let me look at the text thread. Someone said, “We have a lot of green cabbage and not much else.” And then someone else is like, “I can make ratatouille.” That’s literally as far as we’ve gotten.

Summer produce is at its peak right now. What are you obsessing over?

Tomatoes are just a gift. We plant so many in the yard, but I’m also constantly buying them. Last week, we had a beautiful stew of beans and tomatoes. It’s no surprise to us here in the Bay Area, but I’m just crazy for the dry-farmed Early Girls. I used to can tomatoes, but it’s such a pain in the butt. Now I just freeze them whole on a big cookie sheet till they’re rocks, and then put them in a Ziplock. It gets me through.

Do you ever get to San Francisco to eat?

I wish I knew more about what was happening culinarily, but I’ve become a little bit of a hermit. I do really love Lunette [the Cambodian restaurant in the Ferry Building]. Nite [Yun] is such a great cook. Any time I get to learn about a culture or cuisine that is new to me is really a treat.

You’ve been in the Bay Area for a long time. How do you think being a chef has changed?

When I got a job at Chez Panisse, it was the 28th birthday of the restaurant. Any of the downstairs cooks could have been the chef of a very well-known restaurant. There was just a level of expertise, because they had worked their way up there and been cooking for 20 years, you know? Which meant I got to learn from them.

But now, I think it’s so much more difficult to be a chef. I think capitalism has sped things up — it’s so expensive to live, and restaurants eat cooks up and spit them out. I don’t blame chefs for leaving kitchens and going somewhere where they’re going to make more money.

How much do you and Hrishikesh Hirway talk about the similarities between the making of a song and the making of a dish? I think your first cookbook, “Salt Fat Acid Heat,” could easily have a companion book called “Drums Bass Guitar Vocals.”

The thing we always talk about is just the creative process. It's funny, because I was a fan of “Song Exploder” before I ever knew Hrishi. He said, “Oh, yeah, the more I do ‘Song Exploder,’ the more I realize it’s just a show about the creative process in general.” And I’m like, oh, right, and that is something we both have endless curiosity about.

On Aug. 29, you and Hrishi will release new episodes of your podcast “Home Cooking.” How will they be different from the ones you made during the pandemic?

Well, it’s a different time. It's just a different type of hard. During the pandemic, food procurement was a stress, but now there are largely financial stressors. Food is so much more expensive. Just around the corner at my coffee shop, a scone was $7!

You told me you are always reading one book and listening to another. What are you into right now?

I'm very excited about “My Garden Book” by Jamaica Kincaid. I just started that. I really love nature writing, and I love gardening. It’s a super inspiring sort of place to ground myself.