Judge Chloe Dillon began the afternoon of Aug. 22 with the final hearing of a case for two asylum applicants who had waited 10 years for their day in court. It was a normal day in immigration court during President Donald Trump’s second term — which is to say, the mood was grim, people were scared, and no one knew what the hell was going to happen next.

In the previous two months, several judges had been fired, gutting the court. Dillon and her remaining colleagues were overworked and on edge, grieving the decimation of their institution and wondering who would be pushed out next.

But Dillon kept her focus on the asylum seekers before her. Over hours, the lawyer for the government cross-examined witnesses to an extent that just a few years ago would have been considered excessive. The case took many times longer than it would have last year.

Dillon retired to her chambers to make her ruling and checked her email. She had a new message; the subject was “Notice of Termination.” In an impersonal, single line of text, it informed Dillon that she was fired, effective immediately. No reason was given.

In a blur of activity, Dillon’s supervisor entered her office, having her sign paperwork acknowledging her termination and promising to immediately return any government property. Minutes later, Dillon’s colleagues crowded her office, some in tears, to help her pack her personal effects. Her husband left their 6-year-old at a birthday party and brought their 9-year-old to the court to help Dillon load her car. The asylum applicants who had waited a decade to learn if they would be sent back to their country would have to wait even longer.

The firing was sudden, but Dillon wasn’t surprised. Since Trump reassumed the presidency in January, six judges at San Francisco Immigration Court have been terminated. The judicial bench is down more than 25%, with 15 judges remaining.

Judge Shira Levine was fired Wednesday, according to sources close to the court.

The cuts have hobbled one of the busiest U.S. immigration courts. In the last two years, San Francisco’s court has decided more than 20,000 cases. It has a backlog (opens in new tab) of 121,455.

The Standard spoke with six current and former judges at the San Francisco and Concord courts; the latter was created in 2024 to handle San Francisco’s overflow. All said morale among immigration judges has cratered. Judges and their staffers openly cry while on the job. Some have prepacked their belongings in boxes that sit in their offices, in anticipation of receiving a terse termination email like Dillon’s.

‘The job has become almost unfeasible.’

Former immigration Judge Chloe Dillon

At the beginning of the year, the U.S. Department of Justice employed more than 700 immigration judges. There are now fewer than 600. Immigration courts in left-leaning cities have been hit especially hard. Boston started the year with 18 immigration judges and now has just five. Chicago had 22 judges last year and now has 14.

Unlike many other federal courts, which are part of the judicial branch, immigration courts are part of the executive branch, under the DOJ, making them subject to the hiring and firing decisions of any given presidential administration. Immigration judges have for years argued that their courts should be part of the judicial branch to protect their independence.

“Are they fearful for their jobs? Yes,” said Matt Biggs, president of the International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers, a labor union that represents the National Association of Immigration Judges.

“It’s sent a chilling message across the immigration judge corps that ‘You could be next.’”

For the ten years prior to being appointed an immigration judge, Dillon worked as a criminal defense trial attorney at Federal Defenders of San Diego. The federal government funded her position through a nonprofit dedicated to helping defendants in federal trials access legal representation. San Diego’s proximity to the Mexican border colored the kinds of cases she saw. “ It was very immigration-law heavy,” Dillon said. When an immigration judge position became available in San Francisco, “it was in a lot of ways a natural fit for me,” she said.

A judge since 2022, Dillon let the vast majority of people she saw in immigration court remain in the U.S. In the 515 cases she decided from the time she was hired through 2024, Dillon granted asylum or other forms of deportation relief 97% of the time (opens in new tab). Nationally, immigration judges grant deportation relief in fewer than half of cases.

While this might suggest that Dillon was especially liberal in offering asylum, the numbers can be misleading. Of the asylum seekers she saw, 98% had legal representation, compared with a nationwide average of 84%, according to the Transaction Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University. Asylum applicants at San Francisco’s court typically have greater access to legal, translation, and other supportive services, reducing their vulnerability to deportation.

Immigration law itself also differs between regions. Dillon and other San Francisco judges apply different circuit-specific precedents than their counterparts in Louisiana and Texas, which have lower rates of granting asylum. A credible death threat in an applicant’s country of origin might be enough to get them asylum in a San Francisco court, but not in Houston.

Dillon pointed out that when choosing which judges to scrutinize, the DOJ has weighted the scales of justice heavily in one direction. “No one ever gets fired for not giving asylum to enough people,” she said. “What about judges who reject granting asylum 90% of the time, sending all those applicants back to countries where they might get killed?”

With Levine and Dillon’s firings, the DOJ has removed the three immigration judges with the highest rates of granting deportation relief in the last few years. If the DOJ is firing judges for their perceived biases, it’s a case of cutting off the nose to spite the face, Dillon believes. She said the firings run contrary to the bipartisan goal of shortening the years-long backlog of asylum cases.

“If the concern in this country is that there are too many immigration cases that are not getting decided and there’s this enormous backlog, this is destructive,” she said. “At the end of 2024, the immigration courts were turning the corner. We were deciding more cases than were coming in. And now it’s heading in the opposite direction. Cases are piling up, hearings are getting canceled. It’s becoming a less efficient system.”

Among a cohort of high achievers, Immigration Judge Ila Deiss’ work rate stood out at San Francisco Immigration Court. From early 2019 through the middle of 2024, she handled 1,949 cases — nearly a third more than the next most productive adjudicator. Deiss granted relief from deportation (opens in new tab) in 92% of those cases. She was the Usain Bolt of judges, so far ahead of her colleagues that she could have taken a six-month sabbatical and still been in the lead when she returned. She chalked it up to “work ethic.”

When immigration courts shut down almost entirely during the pandemic, Deiss was one of only two judges in San Francisco who kept hearing asylum cases over video and phone conference. She worried that any hearing she canceled would mean that an asylum applicant who’d already waited years to see her would have to wait even longer. “I believe that justice delayed is justice denied,” she said.

Deiss was confident she had job security. But strange things started happening at court.

Usually, when the Department of Homeland Security moves to dismiss an immigrant’s case, the prospective deportee has 10 days to respond. In May, the DOJ sent a memo informing judges that they could dismiss cases immediately, setting immigrants up for immediate detention.

“That is clearly to me blurring the lines between the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Justice,” Deiss said.

The lines between the DHS and DOJ became even blurrier this spring.

Deiss remembers that the first time she noticed Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers sitting in her courtroom, she was in the middle of explaining the deportation process to an undocumented immigrant at a preliminary hearing. “They didn’t have any badges or anything, but you could clearly tell that they were ICE agents,” Deiss said. “They would sit and watch and glare at people.”

‘This entire institution is breaking.’

Former immigration Judge Ila Deiss

She gave the applicant his next court date. When he exited the courtroom, she heard ICE making a detention in the hallway.

Deiss said this happened two or three times this year. “You would hear a family member yelling for their child or a scuffle of people,” she said. “It was instilling such terror in respondents and … that’s when I realized that this entire institution is breaking.”

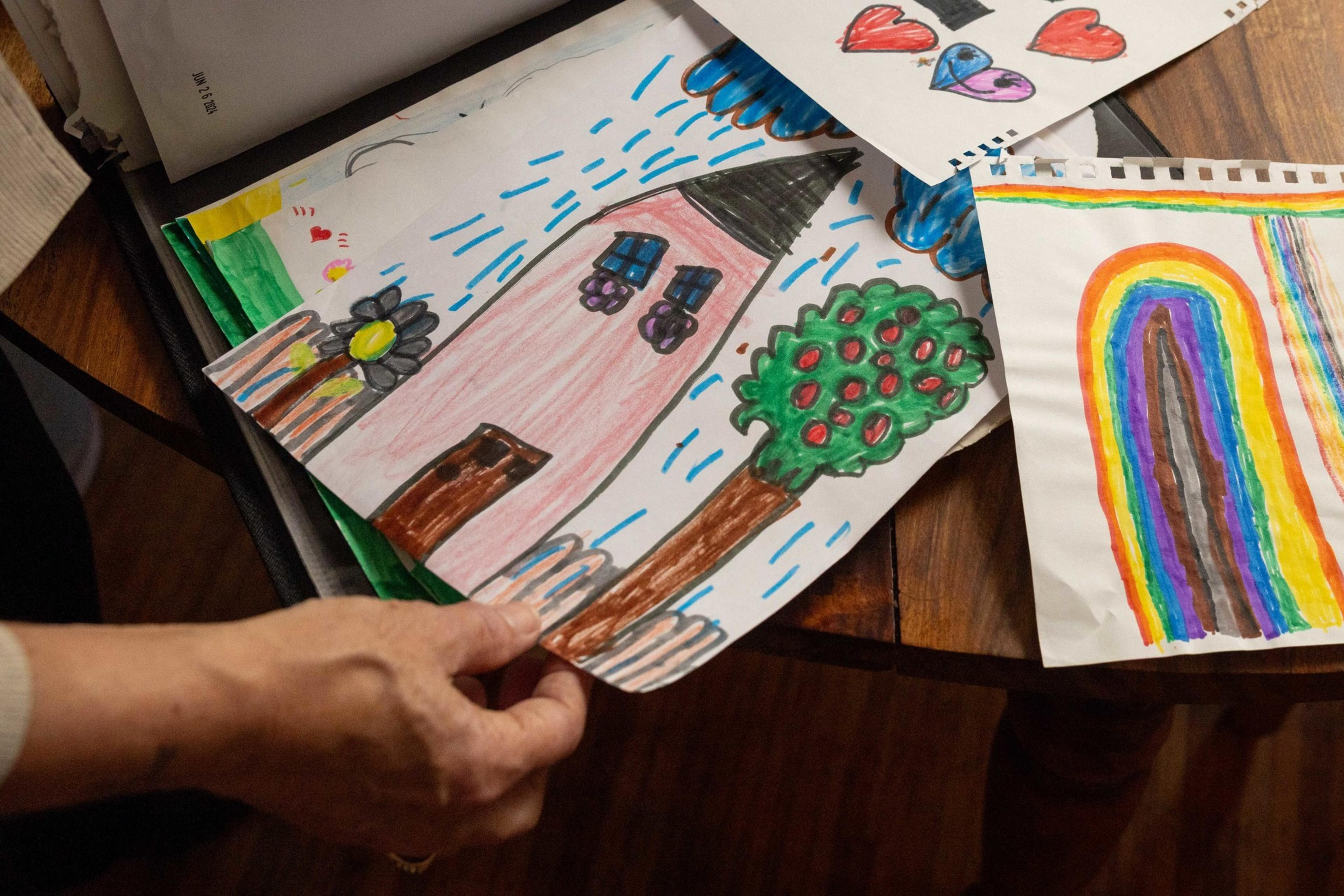

Deiss was fired by email July 17 with a message similar to the one Dillon received: impersonal, three sentences, no reason given. Among the possessions she took home from her office were drawings that children seeking asylum had made while in her courtroom. It was an abrupt end to her 24 years as a federal employee.

“My colleagues left behind are going to think about how they rule and whether they could get fired if they grant relief to somebody,” she said. “They’re very clearly being directed to let ICE do their job by arresting people in our hallways. How can that not impact them?”

The firings have left many questioning the goals of the Trump administration. While campaigning for the presidency, Trump and his allies criticized the years-long wait times for asylum cases. Shrinking the workforce that decides those cases will presumably just back the courts up even more.

“It’s nonsensical,” Biggs said. “You know this administration is going to war with the federal workforce in general. But the one area where you think they wouldn’t be firing are the federal employees that issue the deportation orders.” Biggs recently sat in on a Zoom with more than 100 immigration judges and described the prevailing mood as “shell-shocked.”

While it’s hollowing out the immigration judiciary, the Trump administration is also paradoxically pouring new resources into it.

The recently passed Big Beautiful Bill allocates millions of dollars for the training and hiring of several immigration judges. In late July, the DOJ’s job portal listed an opening for immigration judges in San Francisco. As of Tuesday, that job listing had been removed.

“You can speculate that the intention is to replace these judges with political loyalists that will render decisions on cases the way that the Trump administration expects them to,” said Biggs. To support this hypothesis, he pointed to the en masse firing of all the senior judges who trained new hires. “It makes no sense whatsoever unless you’re gonna replace these trainers with political hacks.”

According to reporting from NPR (opens in new tab), the DOJ has authorized 600 military lawyers to serve as temporary immigration judges. These judges will reportedly receive two weeks of training. Permanent judges take a year to train.

Some have speculated that immigration judges are being targeted for termination based on how frequently they grant asylum or other relief from deportation. The day Dillon was fired, the DOJ’s Executive Office for Immigration Review released a memo stating that although immigration judges “are independent in their decisionmaking in the cases before them,” any who are “adjudicatory outliers” or have “statistically improbable outcome metrics” compared to the entirety of the immigration court corps could be punished.

In other words, if a judge grants deportation relief at a rate higher than the national average, they could be disciplined or fired. That would apply to every judge at San Francisco Immigration Court but one, according to the most recent data from TRAC.

‘It’s a question of whether or not we have a government that believes it needs to abide by the rule of law.’

Former immigration Judge Kyra Lilien

There are also signs that DOJ leaders are pressuring judges to make certain decisions. At least one former immigration judge received a direct warning from a supervisor for not ruling the way DOJ leadership wanted.

The judge, who declined to speak on the record for fear of retribution, said their manager directed them to allow the Department of Homeland Security to move an asylum seeker to another court. When the judge pushed back on the pressure they were receiving, they said they were told, “This is no longer your decision. This is now our decision.”

After hearing compelling evidence from the immigrant’s pro bono attorney that the move would harm their case and was unnecessary, the judge found against the DHS motion, ruling that the case should remain in San Francisco. They were overruled by their manager, who retroactively allowed the transfer.

When the judge objected to this, they said the manager warned them to be careful — that the White House was watching.

The DOJ declined to comment on the firings and judges’ accusations that the administration is impeding their independence.

Some fired judges said they plan to file cases to the Merit Systems Protection Board, a quasi-judicial body that has certified class actions for other groups of federal employees the Trump administration has fired. However, the MSPB likely won’t get any judges their job back anytime soon. And it won’t protect immigration judges who are in the DOJ’s crosshairs.

For those who remain at San Francisco’s immigration court, the workload has become Herculean.

“The job has become almost unfeasible,” said Dillon.

Immigration judges are being asked to hear six or more cases in a day, and each now takes several hours. “You cannot hear six cases in one day and do two to three hours of testimony on each one of those cases. That is an impossibility,” Dillon said.

Kyra Lilien, who was sworn in as an immigration judge at the Concord court in 2023, said the cuts “meant rushing through proceedings in some cases, double-booking cases to ensure that they would complete within a shorter period of time. She added, “We all ended up working much longer hours.”

Lilien’s overtime didn’t save her job. She was fired July 11.

“ I just think that people should know that there is an overall attack on the rule of law,” Lilien said. “It’s really not just a question of whether or not we have immigration courts. It’s a question of whether or not we have a government that believes it needs to abide by the rule of law or whether it feels that it can act with impunity.”