Want more ways to catch up on the latest in Bay Area sports? Sign up for the Section 415 email newsletter here and subscribe to the Section 415 podcast wherever you listen.

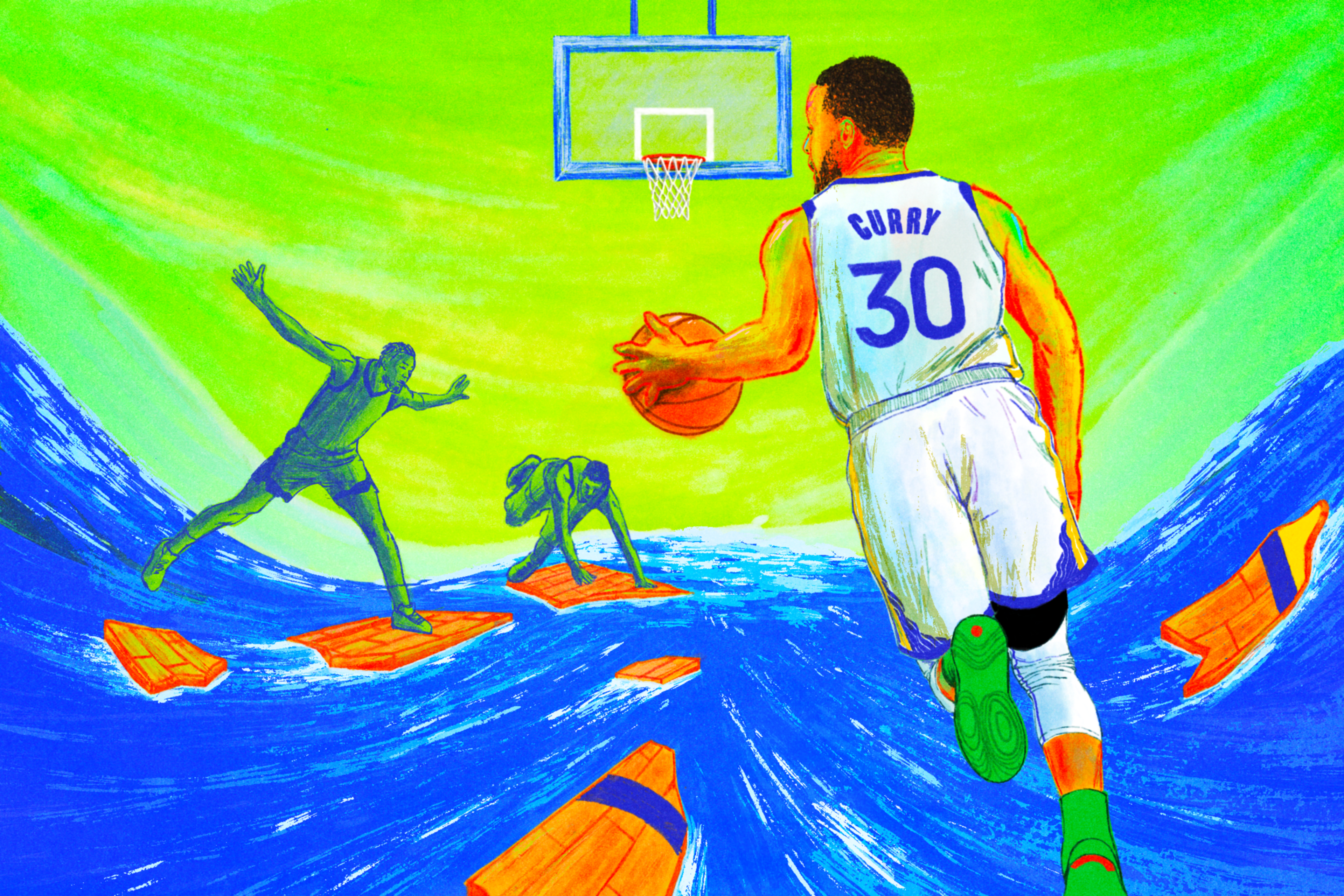

In surfing, “the wash” is the white foam that forms after a wave breaks, creating rough waters close to the shore. For surfers to catch the next wave, they need to wade through the wash, paddling through or around the currents.

Novice or overwhelmed riders can easily get stuck in the wash, frustrated and stressed.

The wash means something very different to Warriors assistant coach Kris Weems.

The wash is Weems’ metaphor for early offense that begins on a specific area on the court: between the two 3-point arcs. The wash usually swells after a Warriors defensive stop or turnover, when Steph Curry catches an outlet pass and turns upstream.

In the wash, teammates are trained to set ball screens for Curry. The two-time MVP can weave behind defenders with their backs turned to him and fire pull-up 3s. His creativity and vision causes cross-matches and panics defenses. It’s where he turns the most aggressive defenses into tidewrack.

“It’s chaotic and usually, if you’re in the flow of transition or whatnot, there’s going to bodies,” Curry told The Standard after morning shootaround in Milwaukee on Thursday. “If a ballhandler’s able to see everything and navigate that traffic and use it to advantage, then you’re able to either get downhill or create space. I get a lot of transition 3s off that.”

The concept has a heightened relevance this year. In the first week of the season, most teams picked up ballhandlers higher on the court than (opens in new tab) in the past. They’re implementing full-court presses at the highest rate of the player tracking era (opens in new tab), taking notes from Golden State’s Saturday opponent, the Indiana Pacers. Curry has noticed it, and the wash is one of the most effective counters to the early-season trend.

After a 120-110 loss to the Giannis Antetokounmpo-less Bucks, the Warriors will need to execute in the wash against Indiana, perhaps the most aggressive defense in the league, to bounce back.

The best way to fight tempo is with more tempo, as long as it’s under control. Staying organized and spaced in the wash around Curry allows him to break the type of ball pressure he’s dealt with his entire career.

“It’s kind of the best time to attack if you don’t have anything to throw ahead,” Weems told The Standard last May. “Us spacing the floor really creates the area that I’m talking about, which is the wash, which is where Steph can kind of weave and get into a certain zone where their bigs are not really sure how to guard him, so they just kind of attack him which allows him to counter and do different stuff off the dribble.”

The wash was on Weems’ mind last spring because of the Warriors’ second-round opponent, Minnesota. The Timberwolves were aggressive, particularly with rangy wing Jaden McDaniels, at pressuring Curry in the backcourt.

Early offense, then, was a major emphasis for the coaching staff ahead of the Western Conference Semifinals. Then Curry’s strained hamstring in Game 1 changed everything. Now, the league’s shift toward higher ball pressure brings renewed focus to Weems’ analogy.

Ironically, Curry and the rest of the Warriors hadn’t heard of Weems’ terminology. Curry’s Davidson head coach, Bob McKillop, drilled it as “traffic,” teaching the guard to change lanes. Head coach Steve Kerr hadn’t heard of the wash specifically, but his eyes lit up when asked about the concept of transition offense and spacing. Weems thought assistant coach Bruce Fraser coined the term because he’s an avid surfer, but Fraser was ignorant to the phrase, too. Fraser does have an oceanic nickname for Curry, though.

“I call Steph ‘The Tuna,’” Fraser said. “Tuna’s one of the fastest fish in the ocean…He swims, like he’s just moving all the time.”

Like a bluefin, Curry is slippery in the open court.

Most defenses are taught to sprint back to the paint before fanning out to the 3-point arc after changes in possession. The Warriors, meanwhile, want to counter by putting the ball in Curry’s hands and sprinting ahead of him. If a defender is sticking with Curry in the wash, the Warriors can set drag screens for him.

Curry’s checklist goes something like this: if there’s a teammate open, toss a hit-ahead pass. If not, push the ball up the court through the middle. If no one stops the ball, get to the cup. If there’s airspace to launch before the arc, let it fly.

“He could come off a drag or kind of weave between bigs with their backs turned, or it may just be that he drives a guy, pushes the ball so hard at guys retreating that he has his heels inside the 3-point line,” Weems said. “That’s like death to a defender trying to guard him. It’s something that we’ve been able to take advantage of.”

One of Curry’s most iconic shots ever came in the wash, when he pulled up from 38 feet to beat Oklahoma City in 2016. The double-bang game-winner was only possible because the Thunder were backpedaling through the wash, giving Curry space to launch.

Quantifying Curry’s exact impact in the wash is difficult. The Warriors have rated poorly in transition metrics for the past several years after dominating in the category from 2014 to 2019 — when Curry was most dynamic.

The number that best exemplifies Curry’s impact in the wash is the Warriors’ on/off numbers in transition. With Curry on the court last season, they were +13.1 points per 100 possessions, ranking in the 99th percentile (opens in new tab).

Earlier this season, Portland gave the Warriors problems with their high pickup points. The Warriors were on the second night of a back-to-back and facing one of the most athletic, young teams in the NBA. Portland picked up ballhandlers higher on the court than anyone last season, according to the ALL NBA Podcast, and have ramped up that pressure even more.

“Certain types of teams, you welcome it, because as much as they think it makes you work, there are counters to it,” Curry said. “The only thing it makes you adjust on is don’t fight it every possession. There’s still ways to get the ball down the court and then get it into playmakers’ hands with live dribbles. Or, every once in a while, nobody can really stay in front of you for 94 feet — blow by somebody, get downhill. But you’ve got to be very decisive.”

On one play against Portland, Curry paced up the floor after a defensive rebound. All five Blazers had their eyes on him, and two sprung a trap on him on the left wing. Sensing the double-team, he passed across the court to a wide-open Moses Moody for a 3-pointer.

The unspectacular play showed just how much defenses freak out when Curry has the ball in the wash. Limitless range will do that to defenders.

Notice how the Warriors space the floor on that play. Brandin Podziemski runs to the corner and Jonathan Kuminga filters across the baseline to the weak side. The Warriors rep how to fill transition lanes over and over in practice exactly for plays like that.

“In the wash, or whatever you want to call it, if you don’t get both corners filled, it just creates a lot of havoc for Steph,” Kerr said last May. “Because the floor is crowded or there’s no outlets against a blitz.”

Curry doesn’t even need to have the ball for the wash to drown defenses. Defending Curry requires constant focus from all five defenders, and any lapse can lead to space — space Curry feeds off. And a lapse in the wash is particularly damaging.

Take this play from the first quarter of Golden State’s win over the Clippers for example. Kuminga holds up at the foul line in semi-transition with the goal of getting the ball into Curry’s hands. Instead of working toward the ball to make himself an option like many point guards are taught, Curry senses Bogdan Bogdanovic top-locking him through the wash, so he breaks to the basket on a backdoor cut.

Kuminga, in one of many fine passes so far this season and a sign of his maturity, finds him with a bounce pass.

Pressing the Warriors is going to be tough if you can’t catch the tuna.

During the NBA Finals, the Pacers pressed on an incredibly high 23% of possessions. They’d led the league during the regular season at 10% and amped it up to force the Thunder series to Game 7.

While Indiana lost Myles Turner to the Bucks and Tyrese Haliburton to a torn Achilles, head coach Rick Carlisle will have his team ready to play on Saturday. And ready to press.

The Warriors have their counter, no matter what Weems or anyone else calls it.

“What does a boy from Kansas, landlocked, know about surf culture?” Weems said. “But that kind of makes sense, you’re kind of just flowing with the way guys are sprinting back, and you’re using them as basically an obstacle course, figure out how to get space with your shoulders square so you can follow through and fire a three. Because that’s such a big part of what we do, that’s what makes Steph great, and it’s what a lot of people want to see in the NBA. If they don’t see a dunk, they want to see a pull-up three.”