The Rena Bransten Gallery, a cornerstone of San Francisco’s contemporary art scene for five decades, is leaving the Minnesota Street Project, the complex of galleries in the Dogpatch, citing a devastating drop in sales over the last year.

“It’s a funny, funny time and it’s a miserable time,” gallery director Trish Bransten told The Standard. “We’re moving out of our space and we’re going to look for different kinds of collaborations, but this is definitely a consequence of not quite enough visitors or sales. I have to wonder after 45 years, are there other models I need to explore?”

Instead of closing altogether, the gallery will adopt a nomadic model, presenting exhibitions in temporary and unconventional venues around the city, providing financial and curatorial flexibility.

The exit is yet another blow to San Francisco’s gallery scene, which, since July, has seen the closures of three local galleries: KADIST, Gallery 16, and Atlman-Siegel, the latter of which was also located at Minnesota Street Projects, the 9-year-old cluster of arts buildings owned by art collectors and philanthropists Andy and Deborah Rappaport.

Bransten’s decision to close echoes what gallerist Claudia Altman Siegel told The Standard when she announced her closure last month: The local art market has screeched to a halt, reflecting a global contraction for fine art. A generation of collectors that once buoyed San Francisco’s art scene has largely aged out, gallerists say, and the next generation has yet to step up. Simply put, very few people in San Francisco are buying art.

Unlike Atlman Siegel, whose roster of artists will be without representation after the gallery closes later this month, the Rena Bransten Gallery will continue to represent its high-profile artists, from filmmaker John Waters to visual artist Lava Thomas.

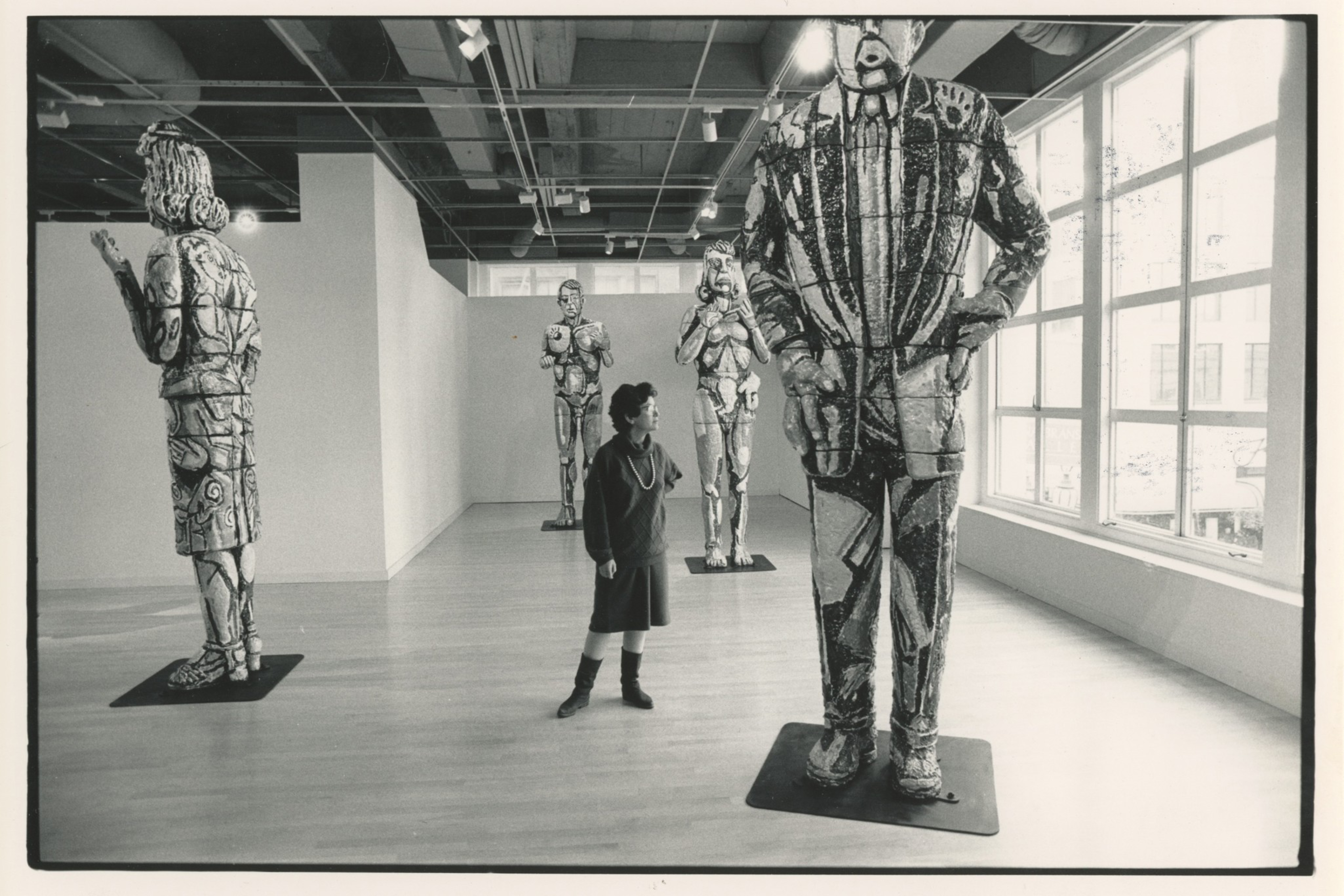

Rena Bransten, 92, founded the eponymous gallery in 1975 in a 3,400-square-foot space in Union Square, quickly establishing a reputation for its trailblazing representation of California Ceramic artists. When a tech company offered their landlord triple their rent in 2015, the gallery was forced out of its longtime digs and settled on Market Street before finding a permanent home in the Dogpatch in 2016. Bransten and other gallery owners were drawn to Minnesota Street Projects for its promise of providing low-cost tenancy for galleries at a time when artists and art dealers were struggling to keep up with the rising cost of doing business in the city.

Yet, nearly 10 years on, as the art market continues to slow and rents rise across the city, gallery owners like Bransten and Altman Siegel are grappling with the new reality that the current model of selling art in a traditional gallery may no longer be viable.

“I looked for a year and a half for a space to move to in the aftermath of the pandemic, but the prices never went down,” said Griff Williams, the former director of Gallery 16, after closing his gallery in SoMa. “With the demise of the [San Francisco] Art Institute, I think it’s left a real hole in the cultural community of the city.”

The nomadic model of selling art has become increasingly popular since the pandemic, with galleries opting for pop-ups that offered unique curation opportunities, collaborations, and greater economic flexibility.

“This new kind of space poses an alternative to the contemporary exhibition format, one that is more inclusive and accessible than its peers,” Jack Chase told Artnews (opens in new tab) of his mobile U-Haul gallery, which he parked outside of mega-galleries during New York Art Week earlier this year. “The mobility of the gallery allows us to capitalize on the foot traffic of established galleries and institutions, as well as show work in unconventional areas (sporting events, public parks).”

Last week, the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco — which had left the Dogpatch last fall for free rent at an enormous downtown location called The Cube — also announced it would be leaving downtown to adopt a nomadic model, rather than returning to its Dogpatch location, where it had struggled to make high rents.

If the ICA’s arrival in the Dogpatch in 2022 once seemed like a good omen for the future of the nearby Minnesota Street Project, its departure now feels like an equally powerful sign of where the project stands today.

Despite the exodus of Minnesota Street Project’s two most historic remaining galleries, its founders, the Rappaports, remain bullish on the future of the arts complex, where they say attendance is up for community events like First Saturdays and the Art Book Fair, and where leases remain in high demand.

“We’ve always had a lot of requests from younger galleries and more established galleries that are looking to relocate for space,” said Andy Rappaport. “Our view is that what’s going on is not an issue for the project specifically, but the gallery business.”

“If the community doesn’t want to, or is unable to, buy work from San Francisco galleries, then it’s just going to get harder and harder for San Francisco galleries to survive,” he continued.

Rena Bransten Gallery’s final day at Minnesota Street Projects will be on Nov. 22, coinciding with the final day of Altman Siegel.