Gallery of 19 photos

the slideshow

Much is made of the secrets of the Freemasons, a fraternal order whose symbols appear on everything from the dollar bill (opens in new tab) to the famed concert venue Masonic Auditorium (opens in new tab) in San Francisco’s Nob Hill.

But the Masonic is not only a place to see concerts—it’s also the state headquarters of Freemasonry and boasts a nearly 50-foot “endomosaic” mural (opens in new tab) that includes soil from all of the 300+ California lodges pressed between its acrylic panes, a window filled with cryptic symbolism.

But according to academics familiar with “secret societies” and members of the fraternal orders themselves, all the rituals and hierarchies and handshakes have a much simpler explanation. Groups like the Freemasons were fulfilling a very basic need: community.

“The secrecy is really overdone,” said Margaret Jacob, a distinguished professor of historical research at the University of California Los Angeles. “The only secrets were the passwords and the gestures, so members could recognize each other.”

Anyone could read the minutes of the Freemasons’ meetings, and the secret handshakes and passwords were mainly to keep impostors out, since fraternal orders often provided material assistance to their members in times of need.

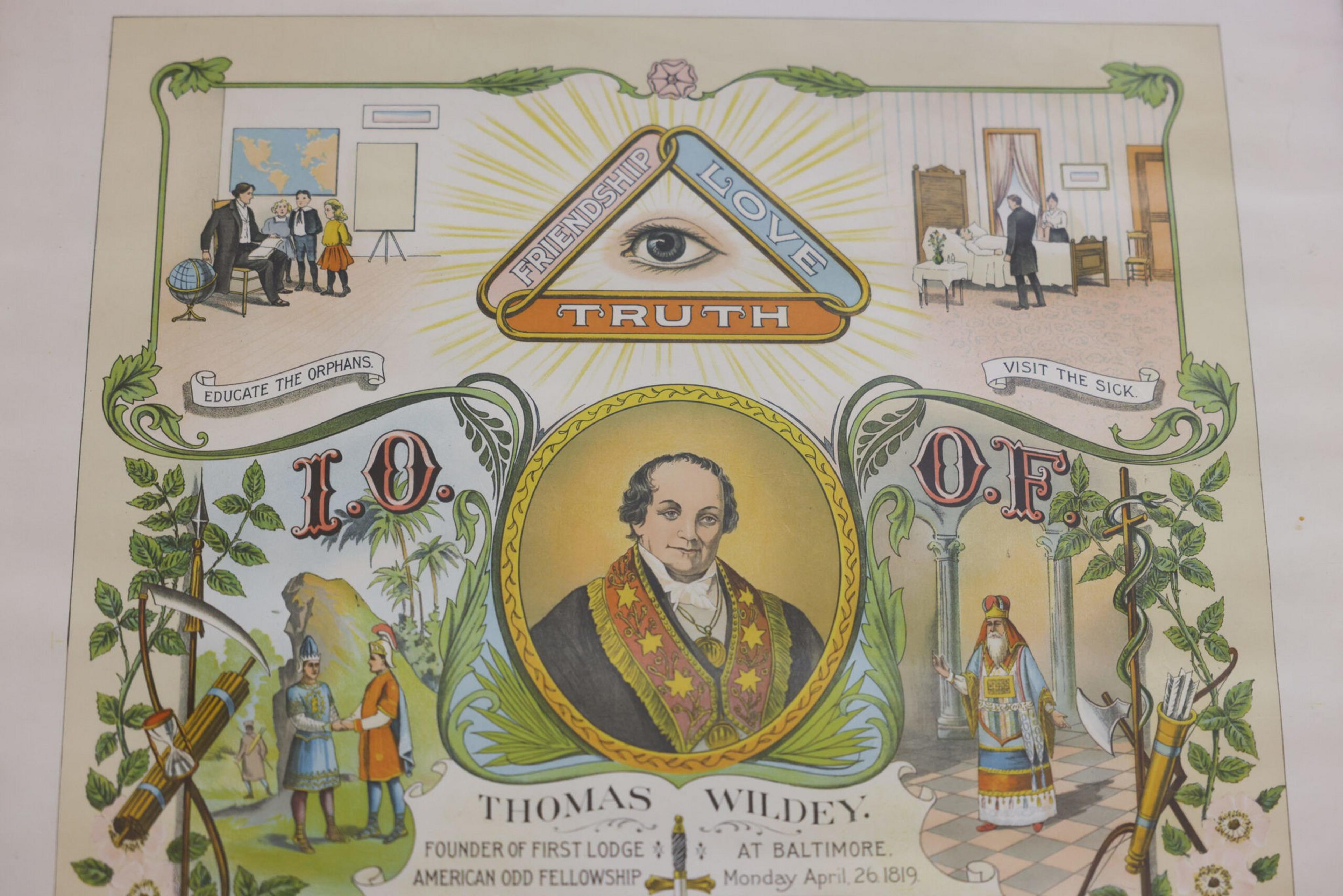

Freemasonry originated in England in the 1710s and took hold in the U.S. in the 1730s—Benjamin Franklin was one of the earliest American members—and has inspired many directly and indirectly related groups such as the Knights Templar, the Odd Fellows and the Knights of Columbus.

“They all imitate Freemasonry,” Jacob said. “Because that was the only model.”

The need for community—and protection—was particularly acute in Gold Rush era San Francisco, when many people arrived in the city alone, without the support of family or friends. They joined orders like the Freemasons and the Odd Fellows to fill in that gap.

“Really, you’re paying your dues so that when you die, your burial fees are taken care of,” said Woody LaBounty, president of San Francisco Heritage. “And if you’re injured, you had funds to support your family while you’re recovering, so it was very early sort of social safety net.”

San Francisco’s Columbarium, the only public place left for mortal remains in the city, is filled with urns that bear the symbols of fraternal orders: the square and compass for Freemasons, tree stumps for the Modern Woodmen of America, interlocked chains for the Odd Fellows.

“The 19th century was the golden age of fraternal orders,” LaBounty said. “Go to a Gold Rush town; you’ll often see the biggest building is a late 1800s fraternal building, a hall put together for networking and business.”

San Francisco continues to be a place where people come without attachments to strike it rich, and the need to forge new social ties is just as important as it was in the 19th century. While overall membership at old-school fraternal orders is in decline‚ engagement with members-only spaces and friendship clubs is on the rise.

“Society is different now,” Jacob said of the Freemasons, adding that many traditional fraternal orders are segregated and exclusionary—even today.

Freemasonry is still only open to men—though there is a women-based order tied to the Masons called the Eastern Star. The Independent Order of the Odd Fellows, which has long had an affiliate organization for women known as the Rebekahs, began accepting women in 2000.

But vestiges of these once-powerful and widespread organizations remain scattered throughout the city—reminders of a fading era. There are still 10 active Masonic lodges in San Francisco, spread across six different buildings. Many more buildings no longer serve the fraternal orders that built them. Today, most of these historic structures support other forms of communal bonding, from religion (opens in new tab) to exercise (opens in new tab).

The Standard took a peek inside three of these storied gathering spaces—an active Odd Fellows Lodge, an active Masonic Lodge and a repurposed Masonic Lodge—to assess the legacy of fraternal orders and their oversized ambitions.

Mission Masonic Center

You could walk right by the Mission Masonic Center on Mission Street and not even notice it—the only symbols of the fraternal order are high up on a concrete facade. The back entrance on Bartlett Street, which today serves as the main entrance, is even more unwelcoming, with a chain-link fence topped by barbed wire edging an empty parking lot.

The setting couldn’t differ more from what’s hidden in the inside: a glorious interior with a community-minded shepherd whose connection to the lodge traces through generations.

“You could say this place is in my DNA,” Jim Lintner, a member of the Mission Lodge who helps steward the building, said. Both his father and his grandfather were members of the lodge, and his parents met at a dance there in 1947.

Despite its ho-hum exterior, the building inside is glorious and full of lore. It was constructed in 1897 after the lodge’s original home at 16th and Valencia streets burned to the ground. The fire after the 1906 earthquake stopped two blocks away, and the building temporarily became a mortuary—bodies were stored in the basement, and survivors identified loved ones in the lodge room.

Its 4-foot-thick brick walls have seen a lot in their time, previously serving as a community post office and a library. In a ranking of Masonic buildings in California, it came in the top five, according to Lintner.

“It’s the jewel of the Mission,” Lintner said.

The Mission Lodge meets every Tuesday, when they gather for dinner and sit on the original cane chairs from 1897—still in perfect condition, with “ML” carved into the wooden backs for “Mission Lodge.”

The lodge room itself is similarly pristine, a grand hall with copper-lined doors, intricate molding and stained glass. Upholstered thrones of dark wood stand on each side of the room, tall columns with spheres that represent the earth and the universe.

The thrones are similar to those for the grand and the vice grand in the Odd Fellows Yerba Buena Lodge, and there are Odd Fellows groups that now meet at the Mission Masonic Center instead of Market and Seventh.

“They’re older, and they’re worried about their safety in that location,” Lintner said.

Much of the Masonic imagery is inspired by King Solomon’s Temple, according to Lintner, with the square and compass representing not only stonemason’s tools but, more importantly, metaphorical guides for how to live your life.

“It’s about keeping your actions square, leading on a good path,” Lintner said. The all-seeing eye is a reminder that God—whatever God you believe in, since Freemasonry is not a religion—is watching you.

While there were 580 members of the Mission Lodge at its height, today it numbers less than half with 220 members, and only around 60 are active. But Lintner is not worried about the decline.

“Masonry’s not going anywhere,” he said. “It’s been around for a long time, and it’s going to be around for a lot longer.”

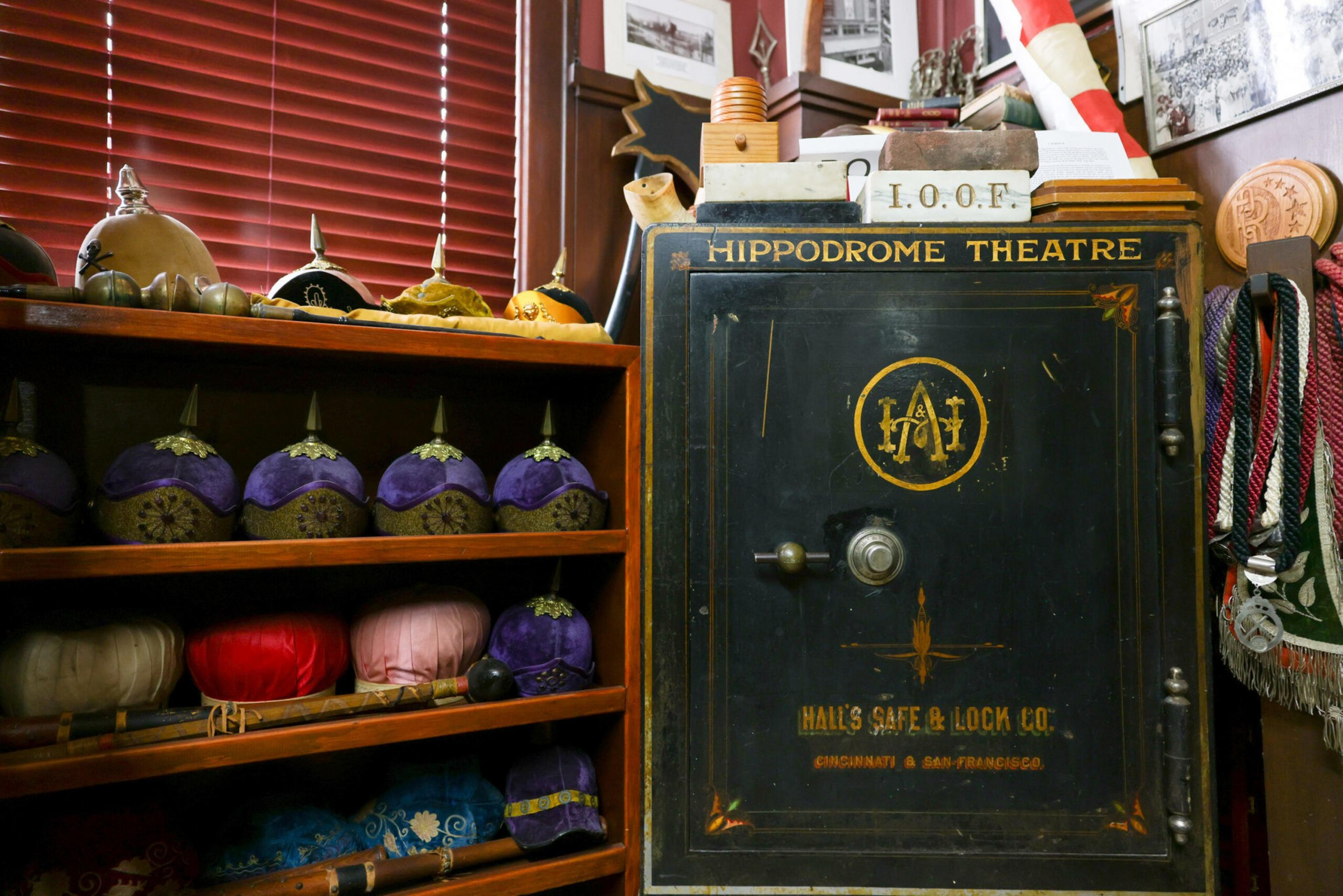

The Odd Fellows Building

Unlike many of the fraternal buildings around town, the Odd Fellows advertise the structure’s purpose with a winged blue sign that screams ODD FELLOWS over Market Street, with the group’s symbol of friendship, three interlocked chain links, at the top.

Yet the building isn’t typically open to the public—which is a shame.

The black-and-white murals in one of the organization’s halls are stunning unto themselves. The oversize paintings are powerful symbols of life’s most foundational elements: a coffin with a skeleton crawling out of it for mortality, a beehive for community, a serpent for wisdom, an all-seeing eye representing a higher being.

But that’s not all. There’s also the Odd Fellows bar room and museum, a cozy lounge filled with ephemera that includes treasures from San Francisco’s history: black-and-white photos of elegant gatherings at the Fairmont Hotel; a 1924 event program that has a real, diamond-studded California gold nugget; antique blindfolds that represent mankind’s darkness.

Three different chapters, or orders, of the Odd Fellows used to meet in the building at Market and Seventh Streets in San Francisco. Today, there’s only one that still meets in person at the location, due to the ongoing safety concerns Downtown.

The six-floor Odd Fellows building was completed in 1909 after the first structure was destroyed to create a fire break after the 1906 earthquake and ensuing conflagration. For much of its time, it was entirely dedicated to the fraternal organization, but it now shares the building with the Alonzo King Lines Ballet and a podcast maker.

The CVS that used to be on the ground floor shuttered in the wake of the George Floyd protests and never reopened, according to David McLaughlin, who helps to manage the building and is also a member of the Yerba Buena Order of the Odd Fellows.

The situation Downtown has deteriorated so much, according to McLaughlin, that the fraternal club is looking into selling the building and moving its organization elsewhere—into a neighborhood like the Richmond.

I-Kuan Tao Zhong Shu Temple

Just as in the Mission, you might pass by the large yellow-colored building at Ninth Avenue and Judah Street in the Sunset without looking up to see the stately neoclassical columns that gird the front. Once the Parnassus Masonic Hall, today, it’s home to a Taoist spiritual organization.

“It was built during the colonial revival,” LaBounty said. “It’s an outsize building for the neighborhood, and it really shows the power of the Masons as trying to be the boosters of commercial strips.”

The Freemasons typically owned their buildings, using rent from ground-level commercial businesses as a way to generate revenue to support their meeting halls on the upper floors.

Constructed in 1914, the former Masonic hall represents a bygone era when the Masons wielded considerable influence in the city and had enough members to publish daily notices in the newspaper.

The I Kuan-Tao Foundation of America, a non-religious spiritual organization, hosts meetings, runs a summer camp and houses a small library—doing the same kind of community-building work the Masons would have attempted, with no password needed.

“The Tao helps to awaken people to have more wisdom in life,” said James Chih in explaining the philosophy—whose lineage traces back centuries and includes such luminaries as Lao-Tzu and Confucius—that guides the center. “What can we do to create less suffering?”

“The family structures are not as strong as they used to be,” said Master Lee, who helms the organization. “There are many mental health crises.”

The Taoist way attempts to highlight gratitude, help others and practice empathy. The organization also wants to ensure people know what the building is—Muni bus line 43, which services the corner long used the name “Masonic Temple” for the stop, even though the building hasn’t been associated with the Freemasons for decades.

Yet evidence of the more than 70-year legacy of the Masons remains—specifically in the pentagram-shaped ceiling inset in the organization’s meeting hall, a reference to the Eastern Order, one that accepted both men and women. Just across town, there’s another such star in the ceiling—in what is today a Live Fit gym.

This story has been updated to clarify that the women’s organization affiliated with the Freemasons is the Eastern Star, while the women’s organization affiliated with the Odd Fellows is the Rebekahs.