The origin story of jeans is a tale woven into the fabric of our city. In the wake of the Gold Rush, an enterprising German Jewish immigrant named Levi Strauss ripped thick denim fabric from sails or tents and dyed it blue, fashioning the very first pair of jeans for hard-working gold miners.

The only problem is that none of it is true.

The first pair of riveted jeans were white, not blue, and they were made from a fabric called “duck” that a tailor named Jacob Davis had purchased from San Francisco wholesaler Levi Strauss. Davis, who was working in Reno, was not outfitting gold miners, but a laborer who had come to Nevada because a major deposit of silver ore had been discovered on the other side of the state.

When Davis saw the success of his riveted pants—he had the idea to attach the metal screws after using them for horse blankets—he asked Strauss to go in on a patent together, with his materials supplier providing the funds. Davis was the brains; Strauss was the capitalist. Yet a company bearing Strauss’s name has been the benefactor of a mythical storytelling that’s both invisible and erasing.

“Jacob Davis was the inventor,” said Frank Davis, the tailor’s great-grandson, who now helms the Ben Davis workwear brand (opens in new tab) based in San Rafael. “Levi Strauss was just selling fabric.”

But Strauss became the single name synonymous with American blue jeans, and there are no descendants of Jacob Davis who own a portion of the nearly $6 billion Levi Strauss & Co (opens in new tab).

It’s easy today to think of Levi’s success as a given, its ubiquity a fait accompli. Yet, according to James Sullivan, the author of Jeans: a Cultural History of an American Icon and a journalism professor at Emerson College, Levi’s was one of dozens—possibly even hundreds—of jeans manufacturers in the 1800s.

What’s more, Levi’s was most likely not the first commercial jeans producer in the U.S., according to Sullivan. That honor goes to Sweet-Orr, a New York-based denim company, which predated Levi’s by two years, according to Sullivan.

Yet unlike clothing brands like the Gap—which used to sell Levi’s jeans exclusively—the brand excels at storytelling and iconography.

“Levi’s figured out brand identity before everyone else did,” Sullivan said. “You’re telling a story by choosing to wear a pair of Levi’s.”

A visit to Levi’s corporate headquarters on San Francisco’s Battery Street, where you can see vintage 501s on display like museum artifacts, drives the point home. The jeans have been worn by characters ranging from a chicken coop keeper to a fashionista to a surfer, torn and adorned to embody the people who wore them. According to Sullivan, Levi’s 501s are the bestselling garment of all time.

Levi’s success might feel effortless, but maintaining the brand’s purity requires serious work. Behind the scenes is a careful curation of identity that has been essential to the company’s century-and-a-half of success—and some good luck. The brand’s dominance rests on a commitment to progressive politics, a robust vintage market and a ruthless pursuit of lawsuits.

Denim Suits

In 2007, Levi’s was rated as the most litigious company in the apparel industry (opens in new tab) for trademark infringement lawsuits. Yet the fervor for intellectual property protection goes back much earlier. It’s arguably baked into the brand’s DNA.

Jacob Davis and Levis Strauss patented the riveting of pants in 1873. That year is considered the birth of the blue jean, prompting its 150th birthday celebration in 2023. In the company’s very first year of denim manufacturing, Levi Strauss promptly sued two denim rivals for selling knockoffs of Davis’ riveted design.

“By taking strong, prompt action to stave off all copycats, Levi Strauss & Co. sent a clear message that inventors would have to come up with other ideas,” denim historian Michael Harris wrote in Jeans of the Old West.

Yet the patent was set to expire in 1890, after which any company would be able to imitate and sell Davis’ design. Levi’s had to come up with another way to differentiate itself in a landscape flooded with denim.

It launched its equine brand logo in 1886, an image that shows two teams of horses struggling to pull apart a pair of Levi’s. The visual demonstrated how tough the pants are and could be easily understood by illiterate workers. The image still appears on every pair of Levi’s sold today, and the company holds trademarks on both the logo’s image and the “Two Horse” brand concept.

But while Levi’s may hold the intellectual property, it was not necessarily the first brand to use such iconography. Sweet-Orr denim had a very similar logo—predating Levi’s—with two teams of men attempting to pull apart a pair of jeans.

Indestructibility is a selling point for denim workwear, so the emphasis on toughness was a common theme for manufacturers in the 1880s. Levi’s main competitor at the time has a brand name that says it all: Can’t Bust ’Em.

The imagery of (unsuccessfully) ripping apart jeans wasn’t limited to Levi’s or Sweet-Orr. According to denim specialist Brit Eaton, jeans from the 1800s include labels from various brands that have bulls, oxen and even elephants trying to pull apart jeans. The Levi’s logo may not have been particularly original at the time, but the company had the foresight to trademark it.

Levi’s continued to add to its portfolio of trademarks over the years: for the words “This Is A Pair of Levi’s,” for the guarantee ticket (paper label) on which the phrase appears, for the word Levi’s, for the red tab on the pocket, for the seagull-shaped stitching on the back pocket known as an arcuate pattern—a shape that is echoed in the present-day “batwing” Levi’s logo, highly effective due to its simplicity and recognizability.

This kaleidoscope of trademarks serves as the springboard for many of Levi’s intellectual property suits, including one that prompted the luxury clothing brand J. Barbour & Sons to call the company (opens in new tab) a “trademark bully.” It’s just one of many clothing companies (opens in new tab) that Levi Strauss & Co. has sued over trademark violations: Vineyard Vines (opens in new tab), Abercrombie & Fitch, Yves Saint Laurent (opens in new tab), Stussy’s, Polo and more.

One suit that hit particularly close to home was against five Japanese denim companies in 2007. The suit nearly shut down the Valencia Street denim store Self Edge—a play on words of prized selvedge fabric—only three months after it opened. Proprietor of the premium jeans store Kiya Babzani declined to speak about Levi’s in an email to The Standard, citing how the company had sued him “in the ugliest way possible.”

Levi’s has also been on the other side of lawsuits. One notable example was back in 1997 when the company lost a $10.6 million suit (opens in new tab) to injured-on-the-job factory workers in El Paso, Texas, then the de facto capital of denim manufacturing, with Levi’s, Wrangler and Lee jeans all made there.

Instead of awarding workers’ compensation to aging employees in an El Paso factory, the manager set them up in trailers, which cut costs by getting around the temporary disability benefit.

Sam Legate, the El Paso attorney representing the Levi’s employees, remembered the case as “a bunch of ladies who were abused by corporate America.” After losing in court, Levi’s switched to manufacturing all of its denim in China.

Lark Fogel, a retired attorney who worked the case with Legate, said the green light for the trailer housing must have come from the very top.

“It was important to us to reveal they were very abusive. It was thrilling,” Fogel said of the biggest case of her career, “and also very intimidating.”

Fogel claimed the company’s top brass was defensive when she took their depositions in San Francisco. The company then appealed the decision, “trotting out all their charitable activities, as if that would excuse their behavior,” Fogel said.

Sey It Ain’t So

It’s not surprising that Levi’s would highlight its philanthropy as a defense; generosity has been embedded in the brand from its very beginnings.

In 1897, Levi Strauss donated 28 scholarships to the University of California Berkeley, monies that still exist today. Strauss made bequests in his will to local charities, and the Levi Strauss Foundation was created in 1952 to coordinate the company’s giving.

The brand has also had a progressive identity from early days: It donated some of its first profits to a local orphanage and integrated its factories in the 1940s.

This legacy has carried over to the modern day in the form of progressive policies: CEO Chip Bergh has banned guns in Levi’s stores (opens in new tab) and been outspoken on social issues ranging from immigration to LGBTQ+ equality to abortion.

In 1992, Levi Strauss & Co. became the first U.S. employer to offer full medical benefits to unmarried employees’ partners, and in 2000, it began allowing full-time employees to receive their regular pay for up to five hours a month of volunteering.

Such activities set a high standard for the brand to live up to and can distract or deflect from the company’s actual purpose: to sell jeans. And some question the potential inconsistency of a brand that champions free expression, but only allows certain voices to be heard.

That’s according to Jennifer Sey, former president of Levi’s who left the organization in a swell of controversy.

Sey began at the company as an assistant marketing manager in 1999 and worked her way up to brand president in 2020—the first woman to do so. Sey was by all accounts an invaluable employee and poised to become the company’s first female CEO. She developed the brand’s “authentic self-expression” slogan and saw the stock double in price under her leadership.

But when Sey became active on Twitter questioning school closures and mask mandates—and then made an appearance on Fox News—the company’s corporate communications department went on high alert, eventually forcing out the seasoned executive in February 2022, after which Sey wrote a viral essay (opens in new tab) about her experience.

Sey does not fit the mold of a right-wing conspiracy theorist, pointing out that she voted for Elizabeth Warren in the 2020 Democratic primary. She was the executive sponsor of the Black Employee Resource Group at Levi’s and a producer of Athlete A, a documentary about abuse in elite gymnastics. (Sey is a former professional gymnast).

“The position I took should have been one that was embraced by the left—standing up for children and public schooling,” Sey said. “And yet it was considered unacceptable because it went against the left-wing orthodoxy.

“And so suddenly, this idea of inclusion and your voice, which was the campaign I created, applied to everyone but not me, because I was saying the thing that was considered unacceptable,” she continued. “There’s a lot of hypocrisy.”

But Levi’s is a brand built on its progressive platform—so known for being “woke” that there was a Saturday Night Live sketch about it (opens in new tab) back in 2017—and when Sey countered public health advice, she became too much of a liability.

According to Sey, the issue of corporate grandstanding on social issues, what she labels “woke capitalism,” has become a problem that has permeated business culture to a dysfunctional degree.

“I spent an accelerating portion of my time in my final two or three years on fielding questions and challenges from disgruntled employees who wanted us to take a stand on every issue,” Sey said. “There were weeks where it was at least 50% of my time.”

“I think the best thing to do is to get back to focusing on making great jeans and stop with all this virtue-signaling,” Sey said.

Levi’s did not respond to multiple requests for comment on this story. Yet what Sey sees as problematic, others identify as key to the brand’s ongoing success.

“They understood quicker than some other consumer goods companies that it was to their benefit to show a social conscience to ensure that people continue to buy the product,” Sullivan said.

If Levi’s progressive politics alienate more conservative consumers, it doesn’t seem to be having an impact—more than 50% of Levi’s customers are Republicans, according to Sey.

Her departure created a void that was ultimately filled in November by former Kohl’s executive Michelle Gass, a hire that dropped the company stock by 3.3% (opens in new tab).

Vintage Threadz

Gen Z adores vintage (opens in new tab): its sustainability, its authenticity, its social media potential.

“For 20-year-olds, 25% of their closet is vintage, and they’re buying it for socially conscious reasons—they don’t want to support sweatshops,” said Brit Eaton, denim collector and organizer of the Durango Vintage Festivus in Durango, Colorado. “Vintage holds value and lasts longer.”

Levi’s succeeds not only because of its dogged pursuit of trademark infringers and its progressive storytelling, but also because its brand durability is strengthened by the robust vintage market and community of “denimheads” who fuel the demand for authentic, original Levi’s, with high-profile auctions (opens in new tab) demonstrating the accelerating value of vintage jeans.

Nowhere is the vintage market more robust than in Japan, where a pair of the prized “red line” selvedge (shuttle-loomed denim with a red identifying thread) 501s that cost $9 in the U.S. could be marked up to $600, according to Emma McClendon, author of Denim: Fashion’s Frontier.

“Levi’s value always goes up, even though some other kinds of jeans are more rare and scarce and so should be worth more,” Eaton said.

Eaton oversaw the auction of a $76,000 pair of vintage Levi’s at his denim festival to vintage collectors Zip Stevenson and Kyle Haupert. The 23-year-old Haupert put up 90% of the funds for the purchase. According to Eaton, the pair has already received offers for over 20% of what they purchased them for.

“The buying power of some of the youth is impressive,” Eaton said, noting how young collectors will buy bales of T-shirts, mark them up and take that profit to invest in pricier vintage clothing.

The incredible success of Levi’s in the vintage market—the $76K deal is not even the most expensive pair of jeans out there—builds the brand, and Levi’s maintains its own site (opens in new tab) to sell secondhand jeans.

Yet there are some vintage pieces the company is not keen on advertising. The $76,000 pair of auctioned jeans, for example, contain a label indicating they were “made by white labor,” a quality guarantee that appeared on the company’s jeans in the 1880s in the wake of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

The label was highly publicized after the September 2022 auction, with many media outlets picking up on the surprising label from the most progressive of brands. Levi’s, for its part, has a history of trying to prevent this image from coming out into the public.

Yet Eaton doesn’t view the label the same way others do.

“I look differently on that than other people,” he said. “Levi Strauss was a major philanthropist, and this was simply the idea that they don’t employ sweatshop labor.”

Sey, for her part, agrees: “I think it’s absurd to hold a company accountable for standards we have today for something they did well over 100 years ago.”

She encouraged the company to address the offensive language publicly all the way back in 2020—during the wake of the George Floyd protests—when the troubling logo resurfaced on social media. But CEO Chip Bergh decided not to address the matter publicly.

“I wanted to be in front of it; let’s go ahead and apologize,” Sey said. “But our CEO did not want to take that tack. He felt that it opened us up to unnecessary criticism.”

Stitching It All Together

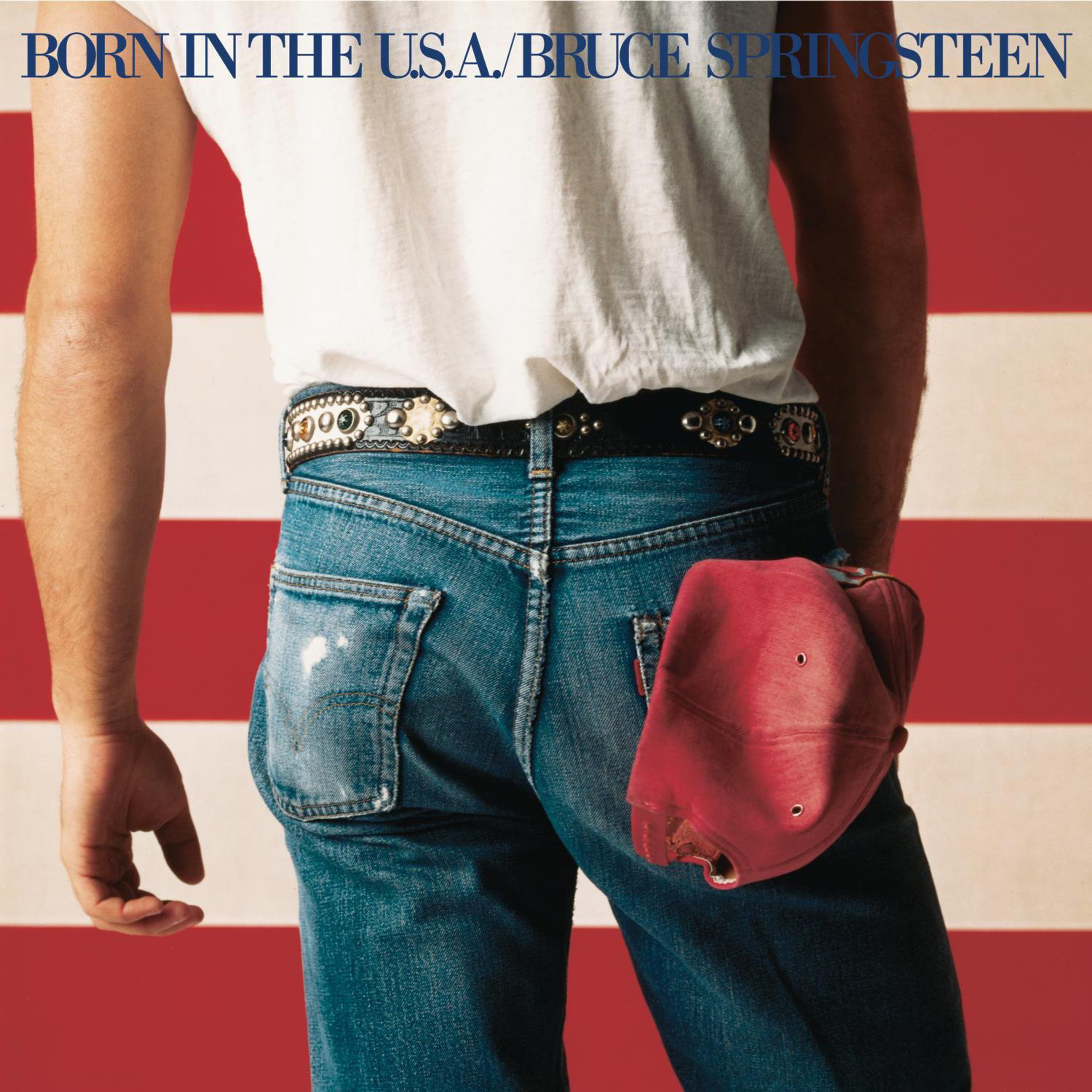

Levi Strauss created a storied, durable brand—visible everywhere, from the pants on Sourdough Sam at Levi’s stadium to Bruce Springsteen’s butt on Born in the U.S.A. Levi’s jeans appeal to everyone, from red meat-eating ranchers who love freedom to Gen Z progressives impressed by quality and trendy collabs. Jeans can be anything.

“Every pair of jeans is a snowflake,” Eaton said. “Like an artistic canvas that gets painted on through time.”

Levi’s has benefited from the storied nature of the garment it sells, with jeans embodying the independence and freedom of the mythical American West.

“There’s this contradictory idea about blue jeans,” Sullivan said. “They’re this mass-produced garment that is essentially for everybody, yet every generation has found a way to wear their jeans in their own style, to create this kind of sense of independence and individuality.”

A recent visit to the Levi’s flagship store on Market Street in San Francisco demonstrates this potential. A tailor sits in the front window, a panoply of patches and customization options beside her. You don’t just buy jeans at the store—you make them your own.

Levi Strauss can’t claim to be the inventor of the blue jean. No one can. But he can be credited with crafting a legend that continues to this day.

“Jeans are like the cockroach of the fashion world,” Sullivan said. “They always come back in style.”