For most of her life, Oakland resident Alison Heller had a crush on a particular guy. Not long after the two finally got together, he died of an overdose. On Valentine’s Day.

It was not the first time a drug-related death shook Heller’s life. Nor was it the first time fentanyl—the extremely potent synthetic opioid increasingly linked to overdoses in San Francisco (opens in new tab) and around the country—was to blame for taking a person she cared about.

“I got to a point when I would get phone calls from my best friends, and I would be too nervous to answer because I didn’t know what to expect,” Heller says.

In the years since, Heller has worked to transform her trauma into meaningful action. As the co-founder of the San Francisco-based harm reduction nonprofit FentCheck, she hopes to save lives and prevent others from losing loved ones with the help of portable, easy-to-use fentanyl testing strips.

Harm reduction efforts like those deployed by FentCheck are nothing new. From the free condoms handed out by Planned Parenthood to the needle exchange programs (opens in new tab) that grew out of the AIDS epidemic, non-profit groups have long provided individuals in high-risk groups with tools and resources to mitigate the dangers they regularly face.

Heller used to volunteer with various street-based harm reduction efforts in the Bay Area. That’s how she first learned about fentanyl test strips. However, she says, in her volunteer work, she mostly distributed test kits to service centers serving chronic, hard drug users.

But while organizations like the San Francisco Drug Users’ Union (opens in new tab) target folks who self-identify—at least privately—as hard drug users, and groups like DanceSafe (opens in new tab) help the hard-partying PLURs (opens in new tab) of the world candy flip (opens in new tab) safely, Heller says not enough is being done to ensure infrequent partiers are smart about the drugs they consume.

It is this population—the casual drug consumers—that Heller and FentCheck co-founder Dean Shold are trying to reach.

“The reality is if you don’t have a tolerance to opioids and you’re buying cocaine to celebrate your 30th birthday or your high school reunion, you are at a huge risk of overdosing from fentanyl,” she says. The same goes for individuals buying black market drugs they believe to be Molly, ketamine or even diverted prescription drugs, such as Adderall or Xanax.

In recent years, news reports from around the Bay Area (opens in new tab) and nationally (opens in new tab) have raised concerns about larger quantities of illicit, non-opioid drugs being contaminated with fentanyl. The San Francisco’s coroner’s office estimates (opens in new tab) that 700 accidental drug overdoses occurred between January and December of last year, with fentanyl being the leading cause of death.

Out of 511 overdose deaths this year, 367 were related to fentanyl. It’s unclear exactly how or why (opens in new tab) the drug is finding its way into other substances, but Heller and Shold are less concerned with that. They just want to keep people alive, as evidenced by their project’s tagline: “Survive the Night.”

The tests FentCheck distributes were developed by a Canadian firm named BTNX. They look and work similarly to over-the-counter pregnancy tests. With illustrated instructions on the back, testers are advised to mix a small amount of a drug with water and dip the strip into the solution for a few seconds. Results are ready in five minutes. Two lines on the strip indicate that the medication is devoid of detectable fentanyl; one line indicates the sample has been spiked.

Heller and Shold pay a little over a dollar per test strip, a cost offset through donations they collect on their website, fentcheck.org (opens in new tab). They also host fundraisers at local venues, like their recent (opens in new tab) karaoke night at Legionnaire Saloon in Oakland, where they also provided training on how to administer Narcan—or naloxone, its generic name—which has the ability to reverse opioid overdoses.

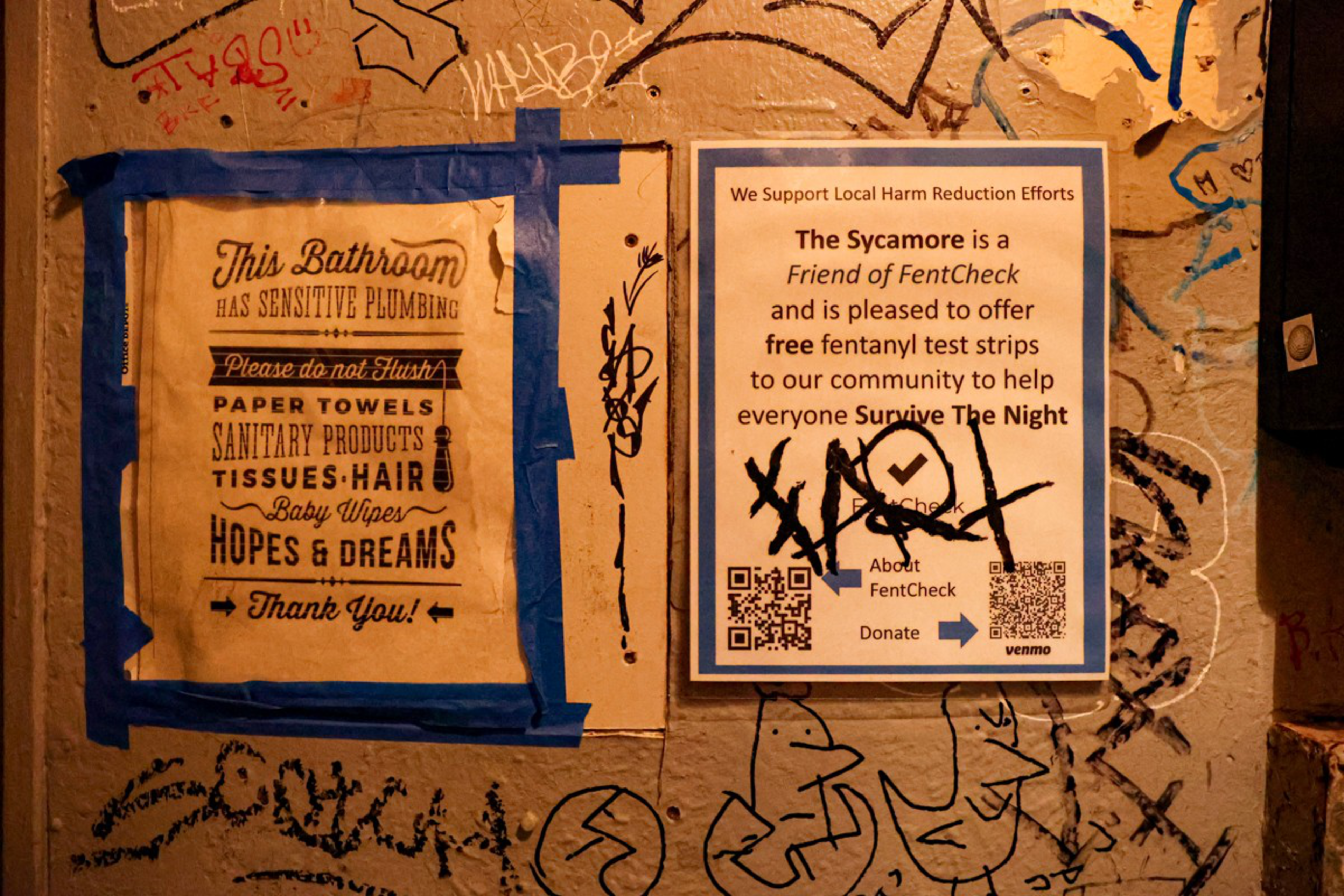

FentCheck supplies fentanyl test strips and naloxone kits to pubs, galleries, tattoo parlors and other community spaces in Oakland, Berkeley and San Francisco. Their website also features a “Check Your Drugs” (opens in new tab) section that explains how to use the fentanyl testing strips and provides a list of measures drug consumers can take to reduce the risk of an accidental overdose. “Use slow and use less,” “space out doses,” and “try snorting or smoking instead of injecting” are among the suggested harm reduction techniques.

The matter-of-fact, non-judgemental tone is meant to engage those who might otherwise run in the other direction when a public health official begins talking to them about drugs. The hope, Heller says, is that those who encounter FentCheck will feel empowered and more knowledgeable about the very real dangers of fentanyl—without feeling like they just got a lecture. If people share the information they obtain through FentCheck with friends and family, that’s even better, Heller says.

“FentCheck is a call to action for our community to step up and have these uncomfortable conversations,” she says.

Heller knows not everyone will like her open approach. Critics of safe consumption sites (opens in new tab) say such initiatives enable or even encourage drug use, and Heller says she has faced similar critiques from harm reduction skeptics.

Numerous venues have declined to carry her FentCheck test kits—perhaps out of fear that it will draw drug users through their doors. But that’s simply not true, Heller argues.

“Walking into a bathroom and seeing a fishbowl full of condoms does not incentivize having sex in the bar, nor do fentanyl tests incentivize the use of drugs,” she says. “It’s not encouraging people to do drugs, but to be safe.”

To protect the identity of their regular users, FentCheck does not share data on the effectiveness of the test strips, but Heller noted that Halloween weekend was a busy time for the organization.

“On the Friday before Halloween, The Sycamore called before 2 p.m. needing a refill,” Heller says of the Mission Street gastropub that carries FentCheck test strips. “We also refilled several other venues at least twice a day throughout the weekend.”

For Heller, calls for refills are extremely validating, and right now FentCheck is handing out around 1,200 test strips each week. But there is another kind of message that is even more reaffirming.

“We got another message yesterday from someone who patronized one of our venues,” Heller says. “They grabbed a free Narcan just on the off chance they would have to use it, and they successfully used it in Santa Cruz. This is our third person confirmed safe from the Narcan we have distributed.”

Senior Editor Nick Veronin contributed to this story.