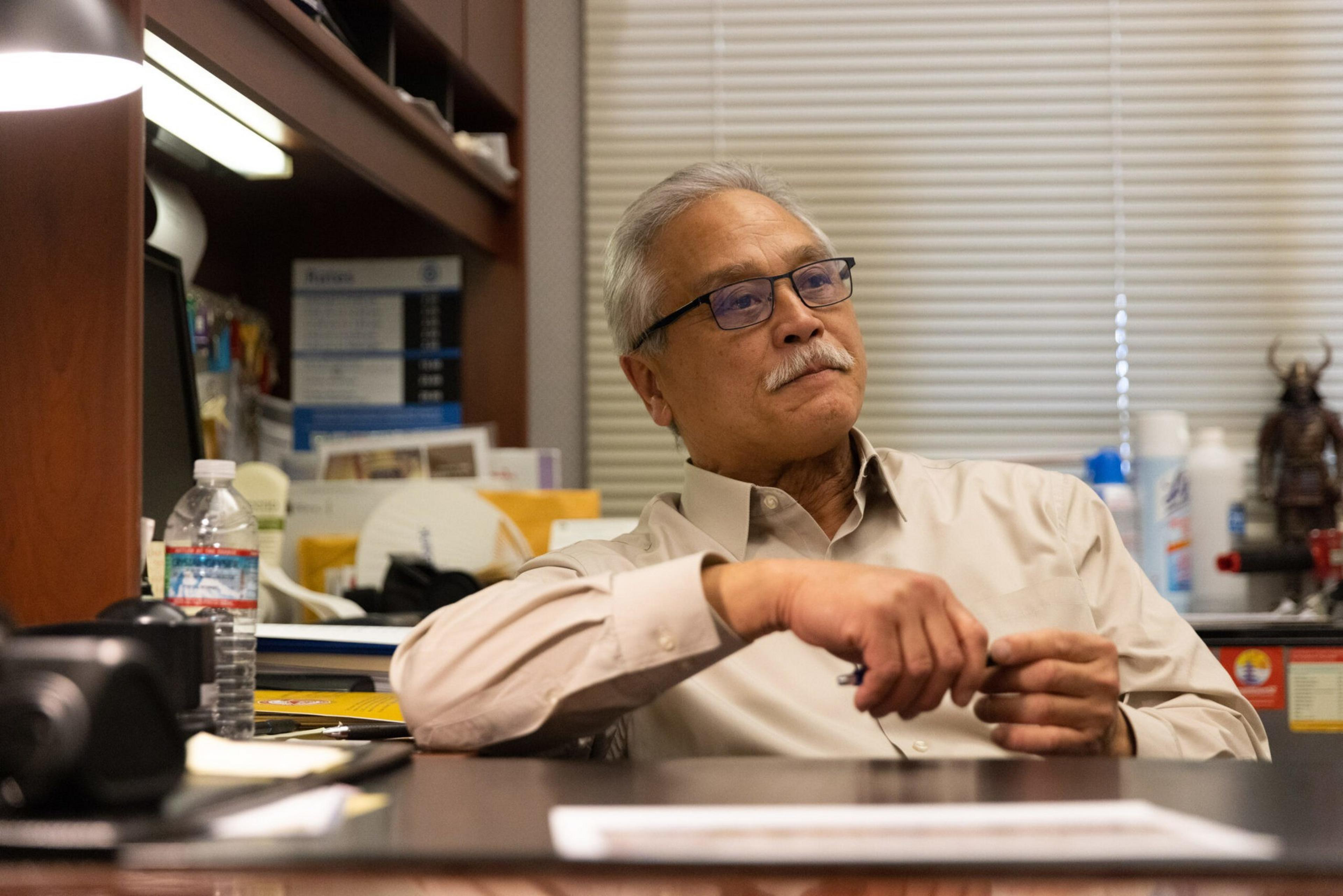

More than half a century after his family was forced to leave their home, Rich Hashimoto, who now heads the Japantown Merchants Association, can still feel the pain and anger.

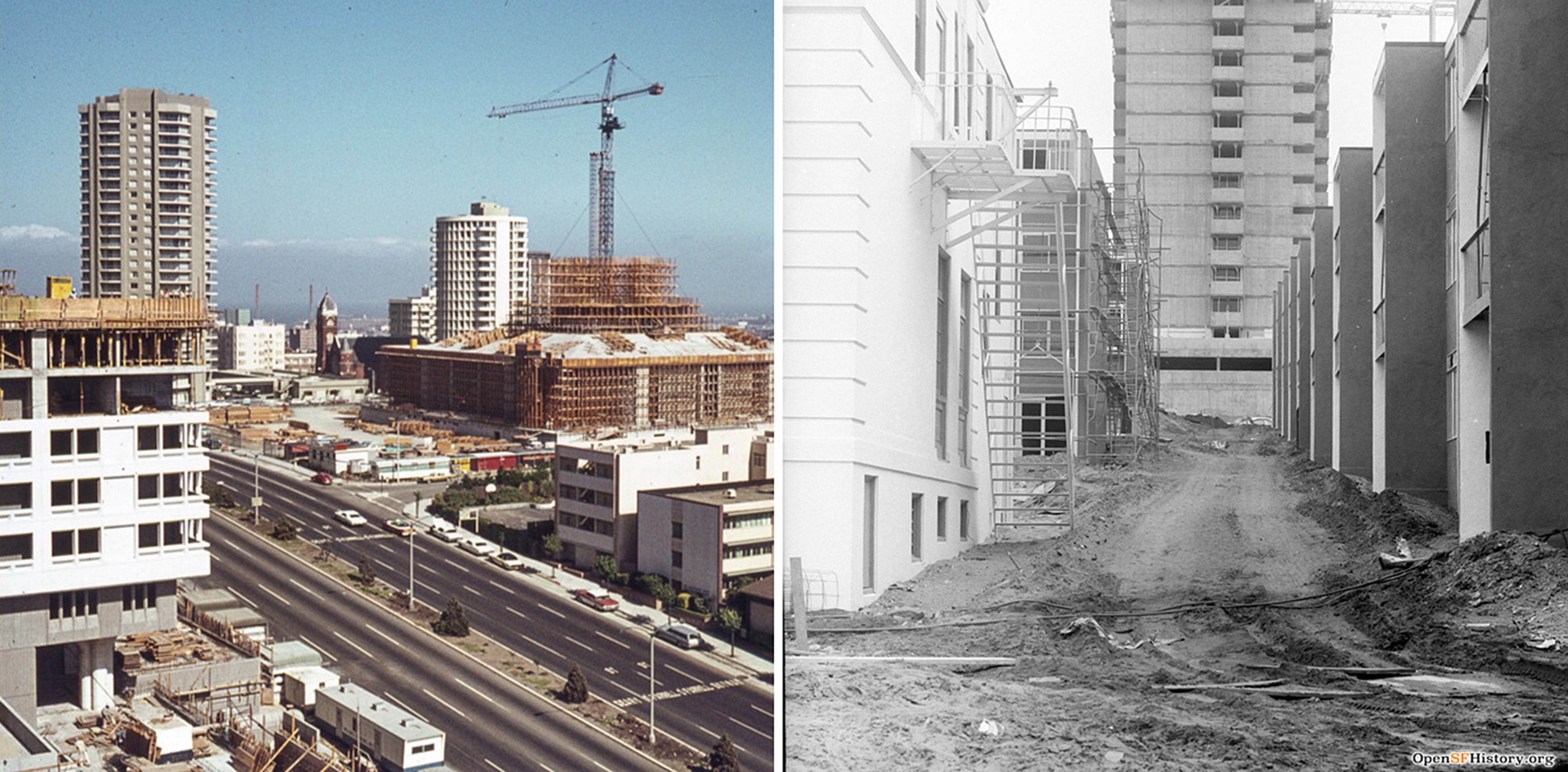

In the 1960s, as many Japanese Americans in San Francisco were rebuilding their livelihoods and recovering from the trauma of World War II incarceration camps, their community was again torn apart. Dozens of blocks were bulldozed (opens in new tab) in the name of urban redevelopment.

“My mom was crying a lot,” Hashimoto, now 64, said. “We were being evicted and had no place to go.”

Generations of Japanese Americans desperately want to see their community thrive, but today their population is shrinking and scattered across the Bay Area. After 14 years of planning, the community has come up with a vision to reimagine this historic area in the hopes of reviving the fortunes of one of the country’s most storied Asian American neighborhoods.

America’s Oldest Japantown

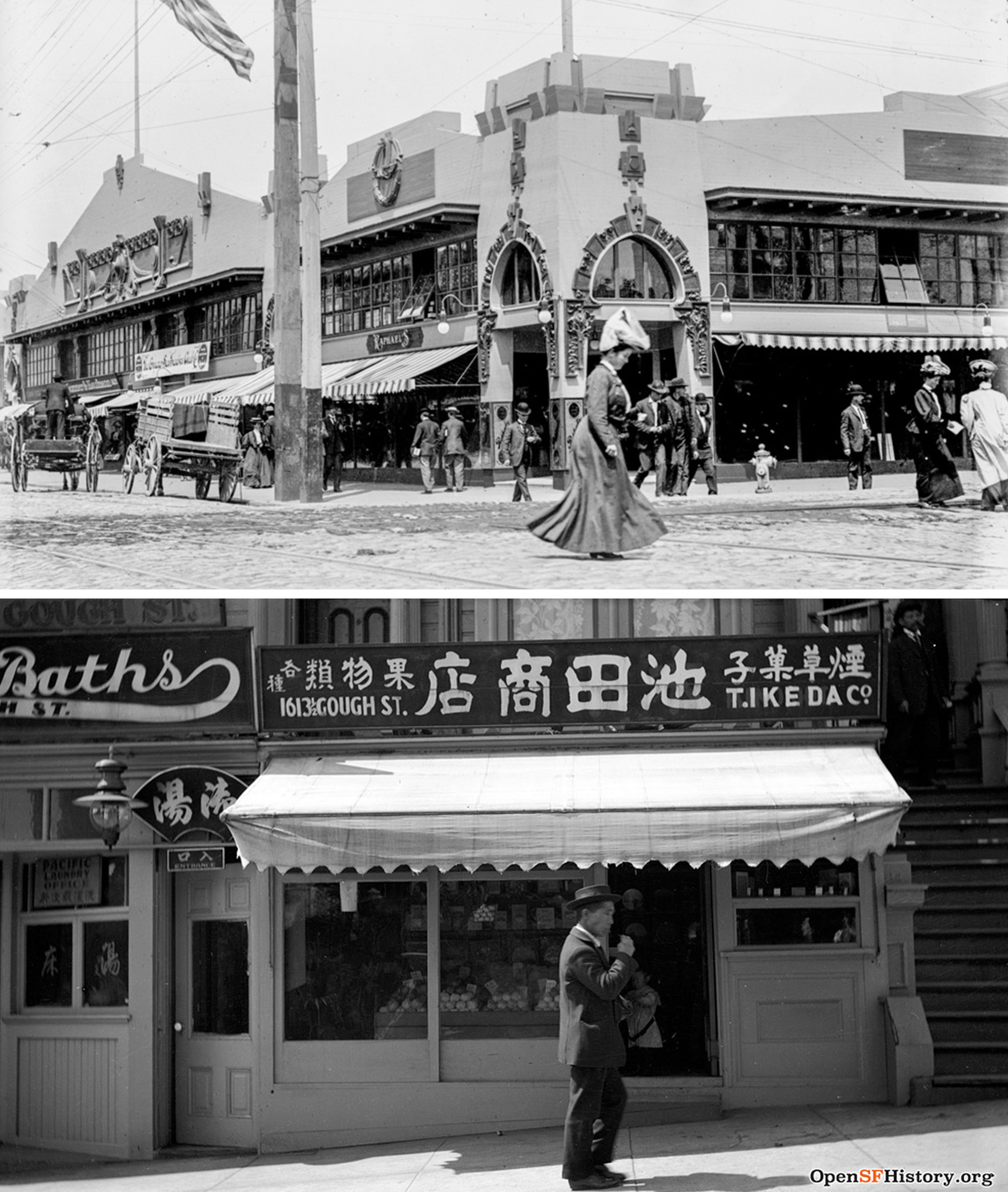

Chinatown and SoMa (opens in new tab) were home to the first Japanese communities in the United States until the 1906 earthquake. After that disaster destroyed most of San Francisco, Japanese Americans and immigrants resettled a few miles away to the section of the Western Addition around Post and Buchanan streets that’s been known as Japantown ever since.

However, while approximately 80 Japanese communities existed (opens in new tab) prior to World War II in places like Salt Lake City and Tacoma, Washington, San Francisco’s Japantown is one of only three that remain. The other survivors (opens in new tab) are Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo and San Jose’s Japantown. Both are thriving, yet San Francisco’s community retains a pride of place.

“San Francisco Japantown is the heart of the Japanese community in the Bay Area,” said Lori Yamauchi, a longtime community activist and the vice president of the Japantown Task Force. “A lot of the Japanese American diaspora considers that to be their home.”

Yamauchi said that during major cultural events like Cherry Blossom Festival in April (opens in new tab), Japanese Americans and expats from across the Bay Area will flock to Japantown and celebrate.

“But they don’t live there,” she said. “So that’s the sad part.”

Twice Destroyed, Twice Reborn

Talking about the rapid disappearance of Japanese American communities, Hashimoto insisted that the causes are straightforward: discrimination and racism.

“The Japanese community has always been the oppressed community,” he said. “First with the incarceration, and then the urban renewal.”

Under the notorious 1942 presidential Executive Order 9066 (opens in new tab), about 5,000 (opens in new tab) Japanese Americans from San Francisco were relocated and incarcerated—including Hashimoto’s father, Harry, who was sent to a concentration camp in Idaho.

Later, in the 1960s, areas of Japantown were designated as “blighted.” The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, under the leadership of Justin Herman, imposed a mass redevelopment plan that forced out thousands of families, largely racial and ethnic minorities. Impacted residents were issued certificates giving them priority to move back into the reconstructed neighborhood’s new affordable housing, as happened with the Black community in the nearby Fillmore District, then known as the Harlem of the West.

However, according to Hashimoto, not enough housing was built, and many families had already moved on with their new lives and new homes, so moving back to Japantown was never realistic. He still keeps his and his father’s certificates.

Rosalyn Tonai, executive director of the National Japanese American Historical Society, said that the consequences of wartime incarceration meant Califorina’s 40 Japantowns were essentially snuffed out. In the case of San Francisco, urban renewal plans razed the housing stock and widened major transportation corridors like Geary Boulevard (opens in new tab), so the community was “sliced up.”

More critically, these discriminatory government practices were conducted with little community input.

“The city leaders did not listen to the people who were living in the neighborhoods,” said Tonai, “So hopefully, this time they’ve learned that.”

One barometer of the shrinking community is the shutdown of Nichi Bei Times (opens in new tab) and Hokubei Mainichi (opens in new tab), both longtime Japanese and English bilingual newspapers. Nichi Bei Times has now transformed to a nonprofit, English-language weekly (opens in new tab).

Hashimoto also witnessed the change through Kinmon Gakuen (Golden Gate Institute) language school (opens in new tab). As a board member, he said the school used to serve over 600 students, learning Japanese in a vibrant setting. These days, it serves only 30 students, operating just one day a week.

Reimagining Japantown

In addition to these historic harms, Japantown struggles with a declining population.

With comparatively few immigrants coming from Japan and a high rate of interracial marriages (opens in new tab), the Japanese population in San Francisco has been dropping consistently (opens in new tab) for the past decade. Recent Census data shows that only 1% of the city’s population, or about 8,000 people (opens in new tab), is Japanese or Japanese American, while many other Asian ethnic groups are growing.

Even in Japantown, people of Japanese descent are rare. Only about 400 Japanese Americans and multiracial Japanese make their homes there, comprising 5% of the area’s population, according to city data. As with Manhattan’s Little Italy, the name “Japantown” is becoming a gesture of affectionate nostalgia rather than a reflection of its inhabitants.

Both Tonai and Yamauchi envision a more diversified Japanese community as the population drops, embracing multiracial Japanese Americans as the new face for the Japanese community. They also emphasized that Japantown’s network of nonprofits has become the modern community’s backbone (opens in new tab).

Emily Murase, the executive director of the Japantown Task Force and a former school board president, said she would like to see Japan-style housing come to San Francisco.

“One dream I have is the mixed, intergenerational housing,” Murase said.

She explained that in Japan, there are tall towers of houses with planned floors, so seniors are living next to young families, which allows older generations to be integrated into society and creates affordable living conditions for young families.

SF’s Newest Cultural District?

To ensure the preservation of its cultural identity and vibrancy for this country’s oldest Japantown, the community is taking action.

Yamauchi, Tonai, and Hashimoto are all part of a team that authored a 97-page Cultural, History, Housing, and Economic Sustainability Strategy (CHHESS) report (opens in new tab), setting the blueprint for Japantown’s future on all major issues. The process of producing this report, with extensive community engagement, has lasted 14 years. As with SOMA Pilipinas, Calle 24, the Castro LGBTQ Cultural District and others, the end goal is a city-sanctioned designation that helps the community prosper.

Major recommendations suggest building centers for tourism, art, businesses and affordable housing; preserving historic landmarks; promoting cultural heritage through events and programs; and protecting residents, nonprofits and small businesses from eviction.

“This document will serve as a source for learning, healing, and reconciliation,” the report reads, “as it addresses the lasting residue of pain and suffering for this cultural community.”

A Board of Supervisors committee has voted unanimously to approve the plan (opens in new tab), and the full board is expected to adopt the plan soon. In spite of more than a decade of work, the strategy report doesn’t mandate any actual implementation or specify any costs yet.

The report also urges the city to work with formerly displaced Japantown families and their descendants to consider options for moving back.

“We have multiple generations who are now seeking to belong and reconnect,” said Susie Kagami, the Japantown Cultural District’s project manager and a lead author of the report. “It’s essential to rebuild Japantown the third time after the pandemic.”

Mayor London Breed, a San Francisco native who grew up a few blocks away from Japantown, said she knows that the community has endured a lot of pain and suffering, and the new plan is essential for preserving the city’s diversity.

“The partnership with the Japantown Cultural District and Japantown Task Force means so much to our city as we work together to preserve, embrace and celebrate the cultural heritage of Japantown and Japanese Americans,” Breed said. She is also a sponsor in City Hall in support of adopting the strategy report.

But for Hashimoto, he’s still healing.

Standing on Sutter Street, where his family home was formerly located, he thought about the no-longer-existing, 40-block-large and expansive Japantown. He appreciated the city’s effort to recognize the wrongdoings and try to make amends, but some harm may never be repaired.

“There was an injustice done here in this community,” he said.