Mikaela Rabinowitz had just started her job as director of data, research and analytics for District Attorney Chesa Boudin when things “really picked up.” It was January 2021, and the recall effort against her new boss was already in full swing. Passing around shoplifting videos on Twitter and Facebook had become a common pandemic pastime, and Boudin’s office was getting barraged with records requests.

What they wanted to know seemed simple: How was Boudin resolving criminal cases?

Rabinowitz, who has 14 years of experience with criminal justice data, knew that answering this question was far more complex than at first glance.

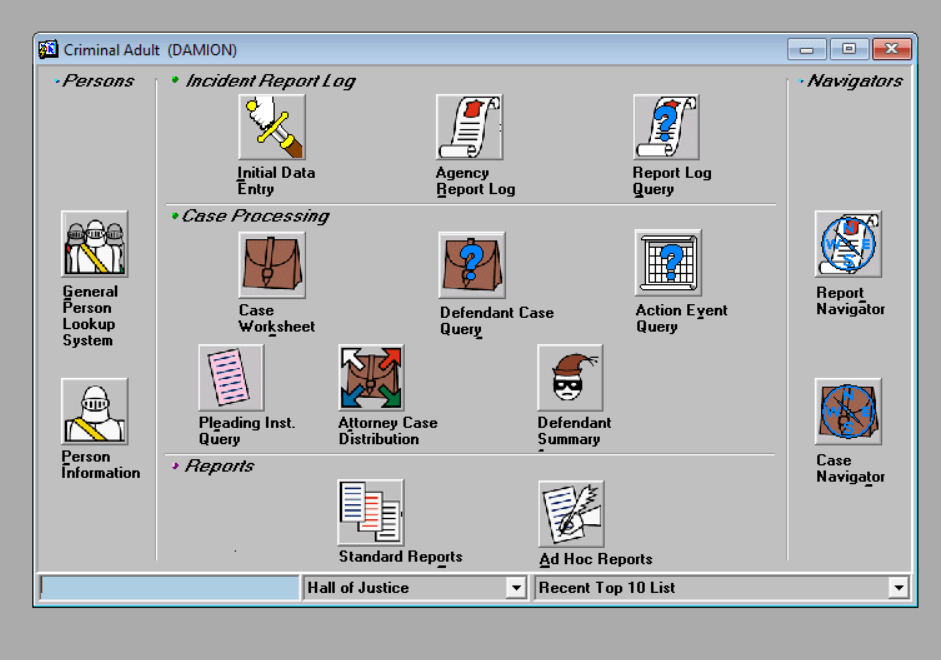

Adding a degree of difficulty, Rabinowitz had to rely on a case management system called DAMION, a cartoonish software program first implemented nearly 20 years ago. The old-school interface icons harken back to 1990s video games like Zelda or the first iteration of Warcraft, and Rabinowitz’s team can’t even get direct access to the database. The office intends to update its case management software later this year, which they say has been in the works for a very long time.

After more than a year of work by the six-person data team—while lawsuit threats came in, including one from this organization—the data dashboard with case outcomes has finally arrived, and the DA’s office is pushing back on any claims it purposefully delayed in releasing data.

“It’s a completely absurd allegation because this was the first office in the state of California to create public data dashboards in 2018 under [former] DA [George] Gascón, and the second in the country after Chicago,” Rabinowitz said. “We’ll get public records requests that ask for data that we literally do not have and then get accused of obfuscating.”

What has frustrated Rabinowitz and her team even more is that data transparency is a central pillar of progressive prosecution, she said, adding that traditional law-and-order DAs usually throw up the most roadblocks to data transparency.

“Traditionally, it’s a black box. The data is completely unknown, and there’s very little accountability,” said Rachel Marshall, Boudin’s spokesperson.

The Standard was able to find only three district attorney’s offices out of 58 in California that have up-to-date data dashboards: San Francisco, Yolo and Los Angeles counties. Santa Barbara County has a dashboard that was last updated for 2020, and several other DA’s offices publish historic statistics that aren’t in dashboards.

Boudin’s robust data team, which includes a data scientist, coder, analyst and diversion specialist, is actually quite rare, Rabinowitz said.

Rabinowitz has a background in criminal justice data transparency. Prior to her current role, she worked at Measures for Justice, a nonprofit that specializes in making criminal justice data public. She also worked on the state’s criminal justice transparency bill AB 1331 and authored a book called Incarceration without Conviction, which looks at the effect of holding people in jail who can’t afford bail.

One reason why it took so long to launch the case resolution dashboard, Rabinowitz said, is due to where case resolution data is housed. The San Francisco Superior Court’s case management system houses this information, which is then fed into the DA’s outdated DAMION system. Due to technical incompatibilities between the two systems, thousands of cases didn’t have the correct codes assigned to them, so Rabinowitz’s team spent a lot of time manually updating cases with a team of paralegals.

A second issue was figuring out how to present the data in a more understandable format. The justice system has thousands of penal codes, and often cases are charged with multiple penal codes. Boudin’s team had to figure out how to categorize penal codes into human-readable charges like arson or burglary.

And finally, since the progressive prosecutor has been so intensely scrutinized, Rabinowitz said it was important to do an even more thorough review than usual.

“We felt a very intense obligation to be very confident in the accuracy of the information,” she said. “Any time we make a mistake, we get attacked.”

Boudin’s data transparency critics are looking forward to seeing more data.

Joel Engardio, whose organization Stop Crime SF threatened a lawsuit against the DA’s office when it was denied information, said he’s happy with the new dashboards, though he feels like the DA’s office “played games” with him during months of back-and-forth about making the data available.

“In particular, we need to understand diversion,” Engardio said, referencing how some cases are steered toward sentences that involve drug addiction programs and other services instead of jail. “We believe in diversion, but the question is: Are diversion programs working? That is unclear.”