In late February, Oakland Councilmember Janani Ramachandran’s 72-year-old uncle, a private security guard in the city, was beaten up during a burglary. A passing cyclist called 911, but it took 50 minutes for police to arrive.

“It’s a huge problem,” said Ramachandran of police response times. “It undercuts my trust in the government. It’s getting worse.”

Long waits for police to arrive—along with extended 911 hold times—have been a well-documented issue in Oakland (opens in new tab) over the past few years, but the latest data shows the problem is only getting worse as the city continues to struggle with crime and residents are increasingly vocal about fears for their safety and property (opens in new tab).

Between 2018 and 2022 (opens in new tab), the time between when residents called 911 to report high-priority incidents—which include imminent physical danger and violent crimes involving weapons— and when police showed up (opens in new tab) went from an average of 12.7 minutes to 19.1 minutes, a more than 50% increase.

Response times to calls reporting in-progress misdemeanors, disputes with the potential to get violent and stolen vehicles more than tripled, going from an already-long average of 1 hour and 25 minutes in 2018 to 4 hours and 24 minutes last year. Response times for the lowest priority calls also saw huge increases in the five-year time span.

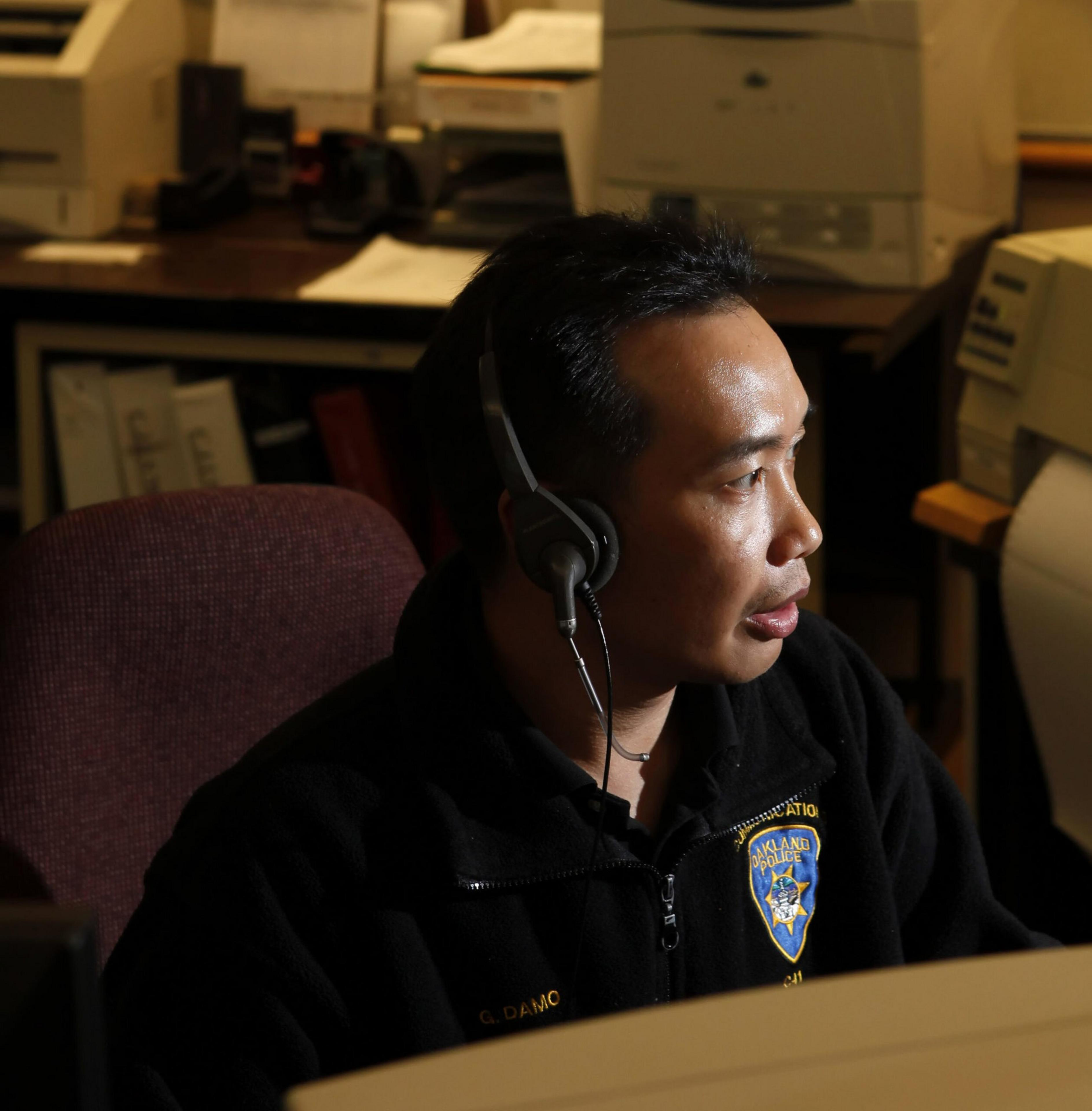

Compounding the problem is the hold time just to speak to a 911 dispatcher.

The police department’s stated goal is to respond to all 911 calls within 15 seconds. In 2021, only about 60% of calls were answered in 15 seconds.

‘People Have Stopped Calling’

Several months ago, Jacob Yates and a group of his neighbors were picking up trash in North Oakland and were almost run over intentionally by a random driver. The wait for a 911 dispatcher got so long Yates ultimately hung up. Luckily, a patrol car was driving by, and the group was able to flag it down and report the incident.

Yates, who recently moved back to Oakland after a 12-year absence, said things are in such a state that many don’t bother to call 911 because they either don’t expect to get through or think that police won’t actually show up even if they do reach a dispatcher.

“People have stopped calling the police because they end up on hold,” Yates said.

Several past analyses—the latest in 2020 (opens in new tab)—primarily laid the blame for long hold and response times on three issues: high call volume; staffing issues related to a burdensome hiring process and comparatively low pay; and police responding to too many low-priority calls.

The Oakland Police Department said it was unable to respond to a request for comment by deadline. However, the head of the Oakland police union, Barry Donelan, said the number of calls for service in the past year has “continued to cascade.”

The Oakland force’s 690 officers received an average of 2,837 daily calls for service in the last quarter of 2022, according to a police department report. Those calls have increased following a spike in murders during the pandemic and a recent rise in robberies.

By comparison, San Francisco—which has almost three times as many police officers—had 1,985 daily 911 calls over that period (opens in new tab). (Although San Francisco has about twice as many people as Oakland, it has a far lower homicide rate.)

Donelan blames the issue on a single cause: inadequate police staffing.

“There are hundreds of calls (opens in new tab),” Donelan said. “The length of time it takes us to get to residents who need help is pretty abysmal, and it’s a function of so few police officers.”

The reality of a lower officer count is inarguable—the Oakland police department has seen its numbers decline from 747 sworn staff in 2018 to 690 last year.

Donelan said that in the recent past, it was considered a critical situation if there were more than 100 callers waiting for police to respond. But now, he said, dispatchers commonly have 200 outstanding incidents. Speaking to The Standard in late May, he said that on a recent Sunday, there were 338 people simultaneously waiting for a police response.

“There’s just no police officers,” he said.

More Police Isn’t the Answer, Some Say

But critics of stepped-up policing say giving more resources to the most expensive department in the city, which they say has mismanaged its dispatching system and how it prioritizes calls, is not the answer.

“There’s a department that receives $350 million plus per year and are claiming with that much money they don’t have the capacity to respond promptly to acts of violence,” said James Burch, who is policy director at the Anti-Police Terror Project (opens in new tab), which advocates for alternative solutions to policing. “That doesn’t make sense.”

A 2021 analysis of police calls for service by the group found that the vast majority of calls were not about violent crimes and therefore—in many cases—didn’t require police.

Burch argued that violence prevention programs and initiatives that respond to low-priority calls without police would both reduce the calls for service and help reduce crime.

In March of 2022, the city launched a pilot program called Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland (MACRO) (opens in new tab) with the aim of responding to nonviolent calls for service using staff trained to respond to nonviolent crises, thereby reducing the number of calls police have to respond to.

However, while MACRO staffers responded to more than 12,000 incidents from April 2022 to April 2023, only a fraction of them came from dispatchers. In all, MACRO only fielded 413 dispatch calls.

Most of their activity came in response to emails or when MACRO staff approached people on the street.

The city plans to use grant funds to expand the program, saying it could help reduce the volume of calls that require police response.

Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao said she takes the response-time problem seriously and has plans to address it.

“Among other initiatives, the council is currently considering a proposal to consolidate 911 and 311 call centers so that we can more efficiently coordinate and deploy,” Oakland mayor’s office spokesperson Julie Edwards said. “Despite a significant budget deficit, we are working to strengthen our public safety systems for all residents.”

Ramachandran said she has some hope for these and other solutions. The budget for the fiscal year starting in July calls for an increase of 20 officers, and the city will soon hire a new head of human resources, who she hopes will quickly hire more dispatchers. There are currently 76 dispatchers, according to the department.

“The answer is not to give up on 911,” said Ramachandran.