It was at the corner of Arguello Boulevard and Balboa Street that Christopher White had his brush with death and found his purpose in life.

While bicycling through a green light, a driver in an SUV took a left turn without seeing him. This is it. I’m gonna die, he thought to himself. White collided with the car and broke its windshield, almost becoming another tragic statistic on the city’s roads.

Sitting in a windowless conference room at the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition’s headquarters on a June afternoon nearly 15 years later, White says the Inner Richmond incident is what sparked him to fight tooth and nail for cycling in this city.

He’s now in the position to do just that: This month, White was named (opens in new tab) permanent executive director of the organization. Hailing from the world of theater, White sports a clean-cut beard, glasses, and a button-down shirt that gives you the impression he may have just come from one of the tech offices nearby—no jean shorts or gauge earrings as far as one can tell.

White’s get-up and vibe serve as a good analogy for how the organization may appear to San Franciscans on the outside today. White insists you call the group “scrappy” as he motions to the coalition’s office and its pretty trim staff and loads of bicycles scattered around.

He’s resolute in how it operates in San Francisco’s politics: “Our approach, our tactics, are more about turning people out for the political processes that make the change happen in the city,” said White. “Showing up, giving public comment, writing to elected leaders, you know, that sort of thing.”

Over half a century after its founding, the coalition is at a turning point. No longer are its members a bunch of angry bikers on the fringes of City Hall engaging in protests like Critical Mass that riled drivers and local electeds like former Mayor Willie Brown. Now, they’ve got a seat at the table with government contracts and the ear of top officials—and have seen several major victories in recent years.

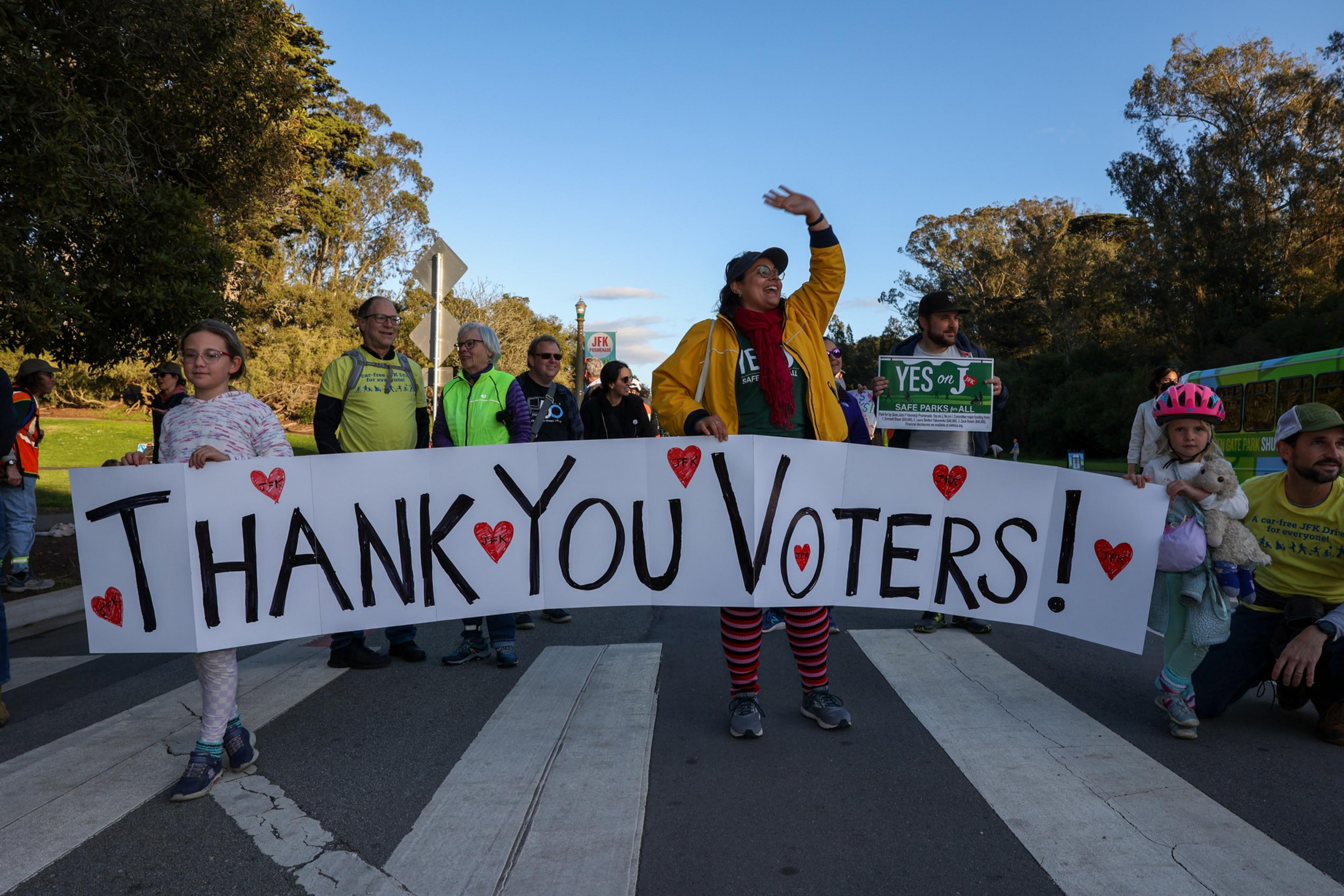

Its crown jewel? Likely car-free JFK, a fight years in the making that transformed how pedestrians and bicyclists move through the city’s most beloved park. White credited the coalition with helping to bring bicycling to some of the city’s low-income, Black and brown neighborhoods long ignored by cyclists. Other wins include slow streets and car-free Market Street.

Now, the coalition is facing its own questions over what purpose it should serve as the politics behind bicycling have become enmeshed in issues like criminal justice and the city’s economic vitality, advocacy that has put it into conflict with other interest groups at times.

“Maybe they’re having an identity crisis,” pondered Jason Henderson, a mobility historian at San Francisco State University and a card-carrying coalition member. “Maybe it’s the midlife crisis.”

As the coalition’s political power has grown, its membership has declined from a whopping 12,000 in the early 2010s to 6,000 today. In pushing for better bicycle infrastructure, it has incurred the wrath of merchant groups, such as businesses along the Valencia Street bike lane in the Mission District.

Some of the coalition’s detractors view it as an extension of the city’s transportation agency. The group has been scrutinized for some of its contracting with the city and its organizational structure. The coalition is split between a 501(c)(3) nonprofit arm and a 501(c)(4) advocacy side, the latter of which can engage in political activity like endorsing candidates in local elections. That setup isn’t uncommon among other organizations in the city.

In May (opens in new tab), multiple SFMTA board members questioned a $1.5 million contract awarded to the coalition for bicycle education. One member, Stephanie Cajina, called it a “red flag” that the coalition was the only organization to apply for and receive the contract.

“I’ve been uncomfortable for some time with this practice,” said SFMTA board member Steve Heminger, pointing out that the organization both receives money from and advocates with the agency. “I’m not alleging any conflict of interest. But I think the appearance weighs on me.”

Last year, former coalition staffer Janice Li and executive director Brian Wiedenmeier were fined thousands of dollars by the city’s ethics watchdog after failing to disclose that they lobbied city officials as representatives of the organization’s advocacy arm. After being contacted by investigators, both retroactively registered as lobbyists and disclosed their outreach efforts.

White said “clear distinctions” exist between the coalition’s nonprofit and advocacy arms: For example, the sides have different boards. He also said the coalition is the recipient of an additional $5 million for its Safe Routes to School program, money that White said goes to a variety of subcontractors.

Then there’s the Valencia Street debacle. Dave Snyder, the Bicycle Coalition’s first executive director from the 1990s, said that the organization could have done a better job rallying supporters of a center-running bike lane that drew sharp criticism from local merchants and avid bikers alike.

The coalition said (opens in new tab) it had “hesitation” about the design, but supported the center bike lane because it was an improvement on the status quo. This sparked backlash from merchants who said the lane had hurt their businesses; some bikers also complained that the lane was difficult to access and left them exposed to traffic risks. This month, officials said the center-running lane, which was installed as a pilot, would be converted to a conventional side-running pathway.

“There are business owners who support it, but you don’t hear from them,” said Snyder. “The public impression is that everybody hates it.”

White said he would like the city to see the pilot program through to collect data on its “novel design” but supports the change. He pushed back on the narrative that bikers and merchants are at odds: “I think that’s just not true,” he said.

All of this change comes at a particularly consequential political moment—one that doesn’t fall cleanly along partisan lines. If polls are any indication, Mayor London Breed, who coalition members and others said has generally been an ally of the organization, could be booted from her seat.

At the same time, there’s been growing suspicion towards new transit infrastructure in parts of the city like West Portal, where merchants recently helped to stall a street redesign after a young family was killed in a crash. Mark Farrell, one of Breed’s leading opponents in the mayor’s race, has pushed back against car-free Market Street and called for the firing of Municipal Transportation Agency head Jeffrey Tumlin, who is generally perceived as bike-friendly.

“We will be looking hard at the track record of folks who have a track record to look at,” said White about its endorsement process.

‘We were a bit more radical’

Established in 1971, the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition came about during a transformational moment for biking as a form of urban transportation. It was no longer just for children or professional racing but a climate-friendly way to get around the city.

For decades, the coalition didn’t enter the political arena. It wasn’t until the 1990s that it started making inroads at City Hall, coinciding with the Critical Mass (opens in new tab) protests that coalition members say helped push the issue of bicycle advocacy to the forefront of local politics. The events attracted around 6,000 cyclists at the height of the protests, with riders blocking traffic and asserting their ride to the road, frustrating drivers trying to get home during rush hour.

“In the past, we were a bit more radical, supporting things like Critical Mass,” said board president Roan Kattouw. “We’re now at a stage where we are an established organization. … And I think that’s great. I don’t think it is necessarily good for an organization working with the city to then go, ‘Hey, we’re organizing this illegal protest over there.’”

The actions arguably worked; by the early 2010s, the coalition boasted roughly 12,000 members.

Then, the pandemic hit. Membership numbers started to drop as people moved out of the city or shaved off certain expenses.

Adding to the tumult, the coalition had its own racial reckoning around the time of George Floyd’s murder, at one point sending out a message (opens in new tab) to its members about the “white supremacy” within its ranks. Around the same time, the group distanced itself from the police and suggested alternatives (opens in new tab) to law enforcement in response to bicycle theft. Some (opens in new tab) criticized the coalition for purportedly not endorsing state Sen. Scott Wiener over his support for police, even though the former supervisor had a track record of supporting bicyclists.

White says the organization is revisiting its approach to enforcement of theft and how to support policies that uphold traffic safety laws, such as automated speed cameras.

The pandemic would also change the fabric of bicycling in the city. With fewer commuters cycling downtown for work, the activity started to center around the city’s neighborhoods instead. That change would leave an opening for the coalition to turbocharge efforts behind car-free spaces, such as JFK.

It would also open up the door for smaller organizations, including groups such as Kid Safe SF (opens in new tab), which was formed in 2021. Safe Street Rebel (opens in new tab), established the same year, is behind some recent guerilla street advocacy, including the coning of Waymo cars and painting curbs red, one of its associates told The Standard.

“I think that’s the first time we had a real coalition,” said Janelle Wong, who served as the coalition’s leader from 2022 to 2023, referring specifically to the advocacy around slow streets. “ I think it has moved the needle politically … This is not just the bicycle lobby.”

A coalition for who?

It’s a question that came up repeatedly with current and former members: Just who exactly should the coalition represent? And how do you keep bicycling relevant, considering there are so many other issues such as housing, homelessness and public safety that are taking up oxygen at City Hall?

“Biking has never been seen as a top issue for the mayor or supervisors,” said former coalition staffer Li, who serves as a member of BART’s Board of Directors. “And I think San Francisco has suffered for it. And if you wonder why people continue to get hit and killed, our city has never prioritized it.”

This month, a bicyclist was killed after a Public Utilities Commission employee in its wastewater division doored (opens in new tab) 70-year-old Steven Bassett, a longtime Bicycle Coalition member. An investigation is ongoing and the coalition has called (opens in new tab) for the PUC to be “open, transparent, and accountable” when it comes to disclosing details about the incident.

Looking forward, White says the focus isn’t necessarily on growing the coalition’s members. “I would say that we’re focusing on building community, that we’re focusing on building an experience around biking that makes people feel like they’re part of a thriving city overall, and if that translates into more members, awesome,” he said.

Wiedenmeier, who served as executive director from 2016 to 2021, said the world of bicycling is “uniquely susceptible” to infighting.

“The coalition was born out of a time and a place where it could be a single-issue movement,” he said. “You were for bikes and for more bikes. It became incredibly difficult to just focus on bikes alone. The world demanded that we respond to other things, [including] housing and homelessness and criminal justice issues.”

San Francisco State University’s Henderson likened the group to the Democratic Party itself.

“There’s aspects of the Democratic Party [where you] hold your nose,” he said. “And I kind of think of the Bike Coalition like the Democratic Party, in a way. It’s a big organization, it tries to do a lot of different things and different approaches. And so you don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater.”