Jacob Peters, CEO and founder of Superpower (opens in new tab) — “the world’s most comprehensive and convenient longevity system on the planet” — is the kind of guy who wears linen underwear and an Oura ring. He also totes digestive enzymes for mixing into his water as a kind of aperitif and carries a jar of grassfed beef tallow (opens in new tab) in his backpack.

The latter, though definitely weird, may not be as fringe as it sounds. If you haven’t heard the news: Beef tallow is in; canola oil is out. The great cooking-oil debate isn’t new but is just now cracking the consciousness of the mainstream media. Whether it’s because of the seed-oil-as-poison (opens in new tab) views of RFK Jr., likely our next secretary of Health and Human Services, or a recent study (opens in new tab) about colon cancer’s link to ultraprocessed foods that utilize seed oil, the handwringing has made it as far as the “Today” show (opens in new tab).

Not surprisingly, there is no consensus (opens in new tab) about the dangers of these oils that are pressed from the seeds of plants and then chemically bleached, refined, and heated. It does seem safe to say that too much of the omega-6 fatty acids found in processed seed oils can cause inflammation. There is also talk of seed oils being especially toxic after reaching the high temperatures needed for deep-frying, and of the dangers of restaurants frying in the same oil over and over.

But if, like Peters, you’re building a business that advises people to steer clear of anything that could shorten their life span, then there’s only one obvious choice: When you go out to lunch, you BYO beef tallow.

On a recent afternoon in December, I joined Peters for lunch at Fang (opens in new tab), a Chinese restaurant near his SoMa office, where he lives for reasons of maximizing his work output. He aspires to tech-titan standards: “Mark Zuckerberg locked himself in a room until Facebook hit at least 100 million users,” he says with admiration.

Peters has other, more personal reasons for his crusade against canola. At 26, after building and selling his first company, he developed Crohn’s disease and endured multiple intestinal surgeries and four months in intensive care. When he exited, he was intent on living differently — if obsessively. He speaks of nanoplastics and nutrient density. He eats a lot of organ meats, like beef heart. He just did a therapeutic plasma exchange.

At 29, he has a long way to go with this regimen. But, in his preppy, plaid-lined jacket and white polo, he presents as more mild-mannered than manic. “In high-grade empowerment, you can develop an overoptimization neurosis, but you can also be stoic and control what you can control. Some people choose ignorance, which can be bliss. [Superpower] is trying to educate people to make decisions.”

You would think one decision would be to just stay home and cook with whatever oil you prefer. Maybe steam everything. But Peters enjoys dining out like most people do — for dates, meetings, and other social purposes. (For those times when he does eat at home, he pays a personal chef to prepare food for him.)

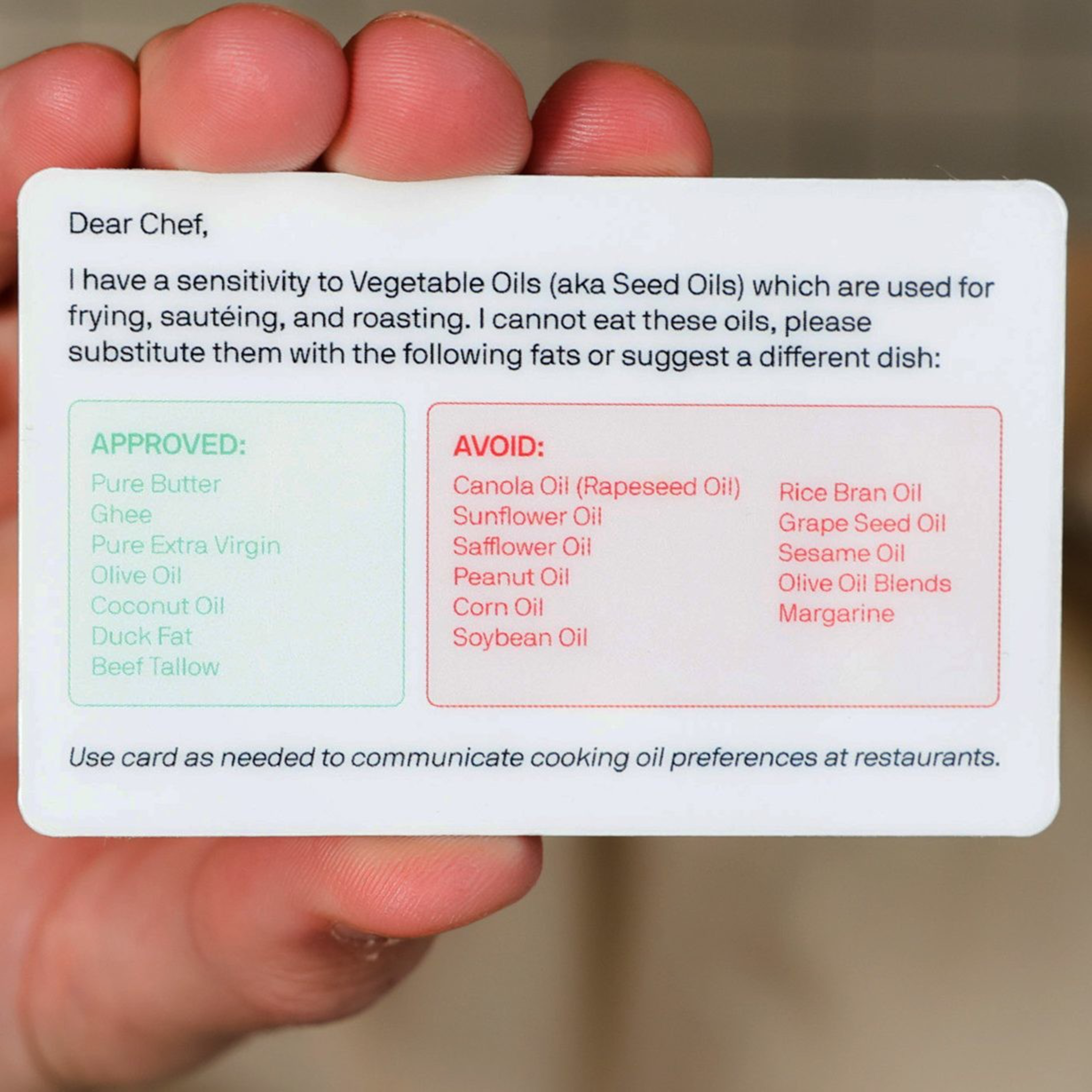

Scanning the menu at Fang, Peters gets ready to order. He takes out a little plastic card he fashioned for Superpower’s subscribers. “Dear chef, I have a sensitivity to vegetable oils (aka seed oils),” it reads. “Please substitute them with the following fats or suggest a different dish.”

The message is followed by a list of what is approved (butter, ghee, extra-virgin olive oil, coconut oil, duck fat, beef tallow) and what is to be avoided (canola, sunflower, safflower, peanut, corn, soybean, rice bran, grapeseed, or sesame oils, olive oil blends, and margarine). In case this comes off as presumptuous, the other side of the card politely adds, “Thank you for keeping me healthy.”

Handed this unusual card, our server sends over the owner of the restaurant, Kathy Fang, who explains that most of the dishes are made with soybean oil. Peters looks at her sanguinely and asks if she’d mind cooking his lunch using the beef tallow he’s brought with him. Fang, a member of the House of Nanking (opens in new tab) family, doesn’t miss a beat. She smiles — maybe a little tightly — and graciously heads to the kitchen, jar in hand. Peters looks relieved. “I’ve been kicked out of a restaurant for asking to do that,” he says. “They said it was a safety violation.”

A few minutes later, a stir-fry of green beans and a plate of Sichuan noodles with chicken are set down. Both dishes are extra greasy, but Peters seems happy enough. Twirling up the noodles with a fork he takes a bite. “It’s hard to say, but I think I can taste the tallow,” he says. “Psychologically, I feel better eating this.”

Peters isn’t the only one brandishing his card. Angel investor Alec Reiss, a youthful 20 (though he has been told his biological age is 17), is one of Superpower’s first members. He recently tried presenting the card at a Thai restaurant in Union Square. “Their initial reaction was like, ‘What in the world is this?’” he says. “And then they started to get it and sort of catered to our needs.”

To him, this wasn’t too much of an ask. “Right now, [the restaurant] is trying to optimize for price instead of longevity. But I think the future of restaurants is going to be catering to diners’ biomarkers.”

For most chefs, who are already crushed by the avalanche of diners’ dietary restrictions, this is their worst nightmare. But at least one restaurateur is all in. “I love it because it is creating the demand,” says Josh Copeland, a former lawyer who in 2021 opened Camino Alto (opens in new tab) in Cow Hollow, where the menu does not use any of the oils known as “the hateful eight (opens in new tab).” “You have to vote with your wallet,” he says. “I sense a shift, but I don’t know if that’s true, when 99% of restaurants have not changed. They want to be profitable.”

Though Copeland claims he’d rather “go down trying” to serve healthy food than put cheaper ingredients on his menu, most restaurateurs are just trying to keep their COGS (cost of goods) in line and their business intact. But in a difficult time for restaurants, it’s also essential to please customers. The line between hospitality and servitude is getting murky. But many will bend for a dollar, even if it involves cooking with schlepped-in beef tallow.

Fang admits that she’s had diners with soybean allergies request the use of a different oil — but not purely for health. She isn’t opposed necessarily, but cooking with olive or avocado oil is exponentially more expensive than seed oils. “We’re trying to make do with what we have right now. With the state that restaurants are in, we don’t have that luxury,” she said.

The financial burden that comes with expensive cooking oils doesn’t really seem to be top of mind for Peters, who thinks that they should start taking some more responsibility for diners’ wellness. Lunch over and takeout boxes full, he parts ways with two words: “Stay healthy.”