The dawn of the Giving Pledge, in the summer of 2010, was a hopeful time: Warren Buffet and Bill Gates, positioning themselves as benevolent billionaires, issued a rousing challenge to their fellow one-percenters to give away half their fortunes. Dozens responded. Major names in Silicon Valley pledged to give away up to 99% of their net worth to philanthropy — and quickly. “Can Warren Buffett and Bill Gates save the world?” one headline (opens in new tab) mused.

Fifteen years later, it’s looking unlikely. A new report (opens in new tab) from the progressive Institute for Policy Studies finds that only one of the living original 57 signatories has given away half their wealth since the pledge began.

Many Bay Area billionaires — the luminaries committed to charting a new course for humanity and a fresh model for philanthropy — have given away less than 20%. One prominent Silicon Valley family has given away less than 1%. In fact, the signatories’ wealth has grown so quickly that the report’s authors now deem the Giving Pledge “unfulfillable.”

“There are bold and direct Giving Pledgers, there are Pledgers who need to pick up the pace, and there are Pledgers who cravenly intertwine personal benefit with their philanthropic obligations,” the report states. “But across nearly every example, there’s proof that the Pledge is unfulfilled, unfulfillable, and not our ticket to a fairer, better future.”

The rules of the Giving Pledge are simple: One-percenters sign on as individuals, couples, or families and pledge to give away half or more of their wealth in their lifetimes or in their wills, with many penning flowery letters about their commitment to doing so.

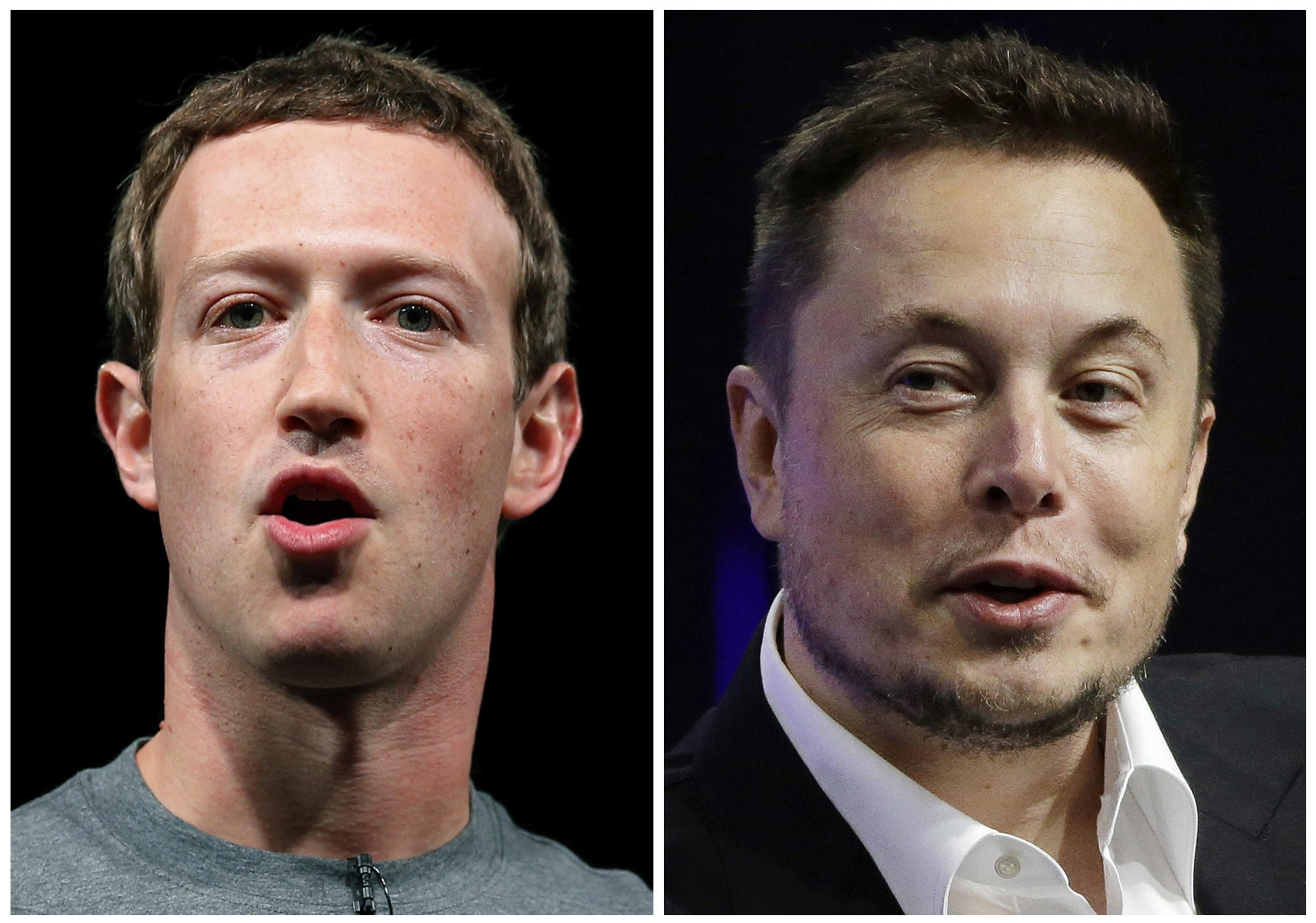

Original signatories included major Silicon Valley figures like Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan; founding eBay president Jeffrey Skoll; and Facebook cofounder Dustin Moskovitz and his wife, Cari Tuna. In the decade and a half since the pledge began, more than 250 individuals, couples, and families from more than 60 countries have signed on, representing trillions of dollars in wealth. (San Francisco Standard chairman Michael Moritz and his wife Harriet Heyman signed the pledge in 2012 and are not included in the report.)

The IPS report, published Wednesday, analyzes the progress of the original 57 signatories and finds they are still miles away from their goal — in part because they are making so much money, so quickly, that they can’t give it away fast enough.

The two Bay Area couples farthest from completing the pledge have also seen the largest gains since signing it: Zuckerberg and Chan, and venture capitalist John Doerr and his wife, Ann.

Zuckerberg and Chan, now the richest of the original signatories, have given away an estimated $9.8 billion, according to the report — more than any donor besides Gates, Buffet, and Michael Bloomberg. (The couple pledged in 2015 to give away 99% of their Facebook shares in their lifetimes.) Still, the authors estimate this number represents only 6% of their total wealth, which has grown an eye-popping 4,244% in the last 15 years.

The Doerrs’ net worth has surged a whopping 617% since 2010. They have given an estimated $101 million to charity, according to the report, including $34 million to their personal philanthropy, the Beneficus Foundation. Doerr pledged to give a record-breaking $1.1 billion to start a sustainability school at Stanford in 2022; the foundation has so far paid out only a small portion of that, according to the report. Doerr and his foundation did not respond to requests for comment.

“My main takeaway is that people are getting way wealthier than they are able to give to keep pace with,” said report coauthor Bella DeVaan. Some billionaires have publicly complained that it is difficult to give away money strategically at the rate they make it, she said, adding: “There’s something absurd about that.”

The report is based on the signatories’ net worth in March; some may have changed since then. It measures how much money or stock the pledgers donated to charity or their personal foundations. The authors factored in the value of the stock at the time it was donated, not how it may have compounded over time.

Even those in the middle of the pack aren’t close to giving away 50% or more of their wealth. Skoll, 60, has donated 17% of his $5 billion fortune, while hedge fund billionaire Tom Steyer, 68, and his wife, Kat Taylor, have given away 13% of theirs, the report says. Silicon Valley philanthropists Pierre and Pam Omidyar, who are in their late 50s, have given away $2 billion — a sizable sum but only 17% of their fortune, which has nearly doubled in the last 15 years. The Omidyars declined to comment; Skoll, Steyer, and Taylor did not respond to requests for comment.

The vast majority of the billionaires’ donations have not gone directly to operating charities or universities, but to the pledgers’ private foundations, the report notes. According to the analysis, $158 billion of the $201 billion the original pledgers have given — about 79% — went to their private foundations, which are required to pay out just 5% of their assets annually. Billions more went to donor-advised funds and LLCs, which have little to no requirements on how the money is spent or reported.

Zuckerberg and Chan, for instance, gave 98% of their donations to the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and its associated foundation. Skoll gave 99% to his foundation, and the Omidyars gave 91% to their collection of philanthropic entities. According to the report, this allows the money to sit in these entities for long periods of time, conferring tax benefits and accolades to the billionaire donors long before the money is distributed to parties in need. (The Omidyars do have an unusually high payout rate, with some of their entities paying more than 60% of their assets on average each year, according to the report.)

The priorities of these foundations can also change suddenly, leaving beneficiaries out in the cold. Recent changes at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, for instance, meant dozens of Bay Area nonprofits that counted on the funding are no longer eligible to receive it. At least one nonprofit temporarily suspended operations as a result.

Wealthy individuals can use their foundations to their financial advantage; for example, to avoid major tax bills. Elon Musk signed the pledge in 2012 but donated relatively sparingly until 2021, when he sold 15.7 million shares of Tesla stock for more than $16 billion. That same year, he donated $5.7 billion in Tesla shares to his foundation — more than he had ever contributed before, according to the report, and likely enough to save $2.8 billion in income tax and $1.77 billion in capital gains tax.

If billionaires continue giving to their private foundations at this rate, DeVaan warned, “we are on the path to having tax-shielded, trillion-dollar, dynastic foundations with the kind of power that we have not seen in the philanthropic landscape.”

In an interesting twist, the Bay Area resident closest to completing the pledge is not a Silicon Valley billionaire but a Hollywood tycoon: film director George Lucas. The creator of the Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises sold his company to Disney for $4 billion in 2012 and pledged to give the proceeds to his foundation. Since then, Lucas and his wife, Mellody Hobson, have given away $3.6 billion — 44% of their net worth — to the foundation, acting charities, and the UCLA film school, according to the report.

Two prominent Bay Area couples appear to have successfully donated themselves off the billionaires list — and in doing so, may have successfully fulfilled the Giving Pledge. Philanthropists Bernard and Barbro Osher have donated $754 million to causes supporting higher education and the arts, the report finds — enough that they are no longer among the billionaire class. Former Citigroup CEO Sanford Weill and his wife, Joan, have also demoted themselves to multimillionaires, the report finds, after giving an estimated $1 billion to Cornell, UCSF, Carnegie Hall, and other organizations. (The ISP report did not include current estimates for the wealth of individuals who are no longer billionaires.)

Moskovitz and Tuna are also making solid progress, giving away some 32% of their estimated $14 billion fortune. As with others on the list, the vast majority of this money went to the couple’s private foundation, the Good Ventures Foundation, which distributes funds in part based on recommendations from Open Philanthropy, an advising firm they cofounded.

While most of the signatories are far from the ends of their lives, and likely have decades to fulfill their pledge, the report finds that just eight of the 22 who have died succeeded in giving away the majority of their wealth. Among them are San Francisco-based Business Wire founder Lorry Lokey and Oakland-based Golden West Financial founder Herbert Sandler.

Even Buffet, who created the Giving Pledge, seems to have realized it will be difficult to get his fortune out of his hands. Buffet previously pledged to will his remaining fortune to the Gates Foundation after his death, but announced last year that he would donate his $144 billion to a charitable trust managed by his three children, giving them 10 years to give it away.

The report’s authors argue that this poor track record suggests the need for more stringent rules requiring billionaires to move money to those in need quickly, rather than relying on a voluntary pledge.

“The track record isn’t exactly inspiring confidence for it to be a self-regulated, voluntary effort,” DeVaan said. “There’s only so long that we can take them at their word.”