Want the latest Bay Area sports news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here to receive regular email newsletters, including “The Dime.”

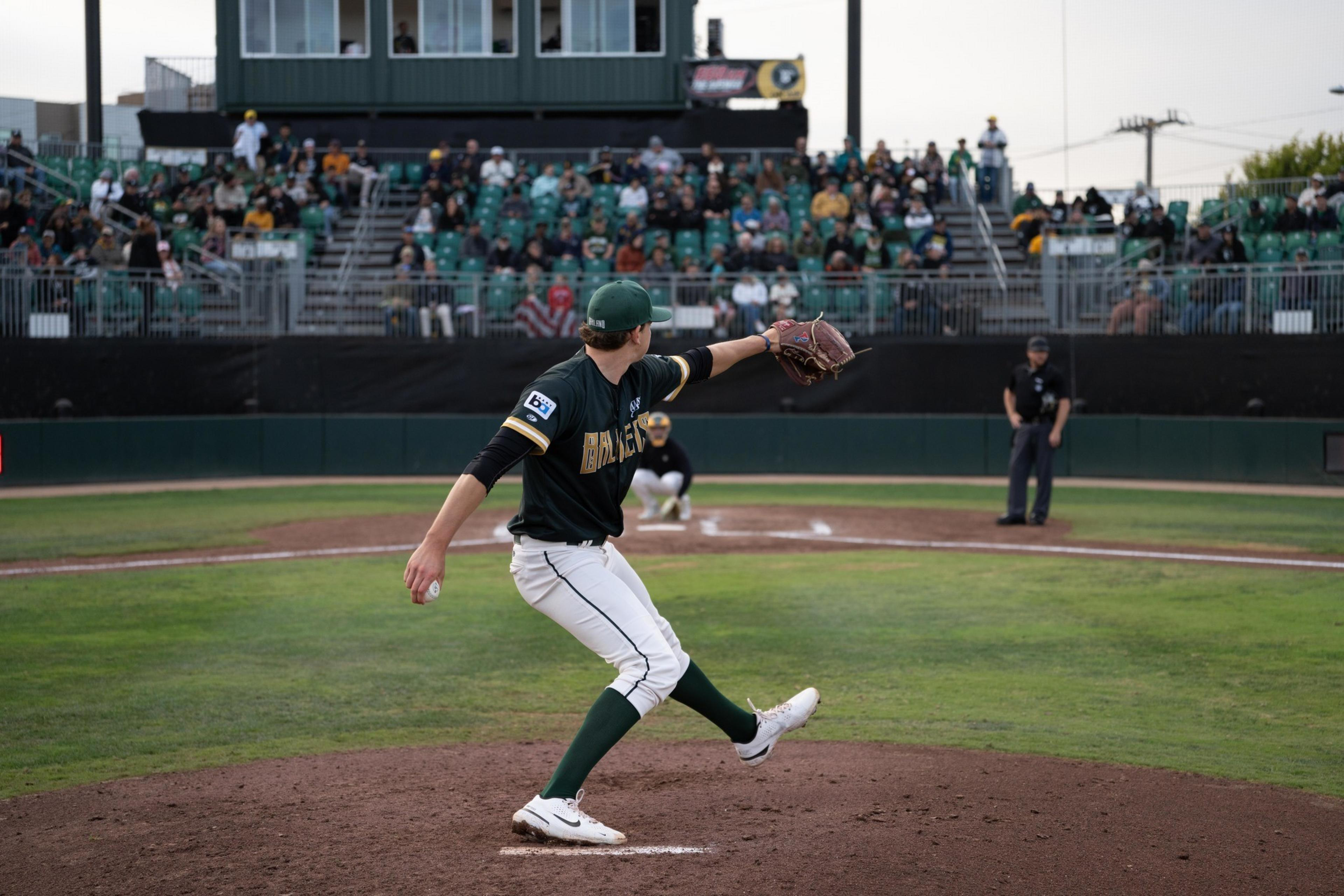

When Noah Millikan’s senior season at Penn started to wind down, the right-handed pitcher wasn’t ready to give up his baseball dreams. But with a 5.31 ERA and an 0-3 record for the Quakers, Millikan’s name wasn’t going to be called in the Major League Baseball draft.

Most Ivy League players pivot immediately, pitching résumés to potential employers instead of pitching in the pros. The Berkeley High product figured he ought to try both.

“I actually found the team; they didn’t find me,” Millikan said. “About midway through my college season, I emailed the Ballers, and I was like, ‘Hey, I’m from the area. Here’s my stats. Let me know if you guys need a pitcher.’”

Millikan had been keeping a close eye on the Oakland Ballers, an independent league club that launched in 2024. Owners Paul Freedman and Bryan Carmel announced plans in November 2023 to start a team after the A’s received MLB approval to relocate the franchise to Las Vegas.

After more than a decade of failed negotiations between the A’s and the city of Oakland to reach an agreement on a site for a new stadium, owner John Fisher chose to rip a beloved team out of a city it had called home since 1968. In the wake of the decision, Freedman, Carmel, and a host of investors determined to keep professional baseball in Oakland were granted the authorization to renovate a dilapidated Raimondi Park in West Oakland, where they hosted their first game in June 2024.

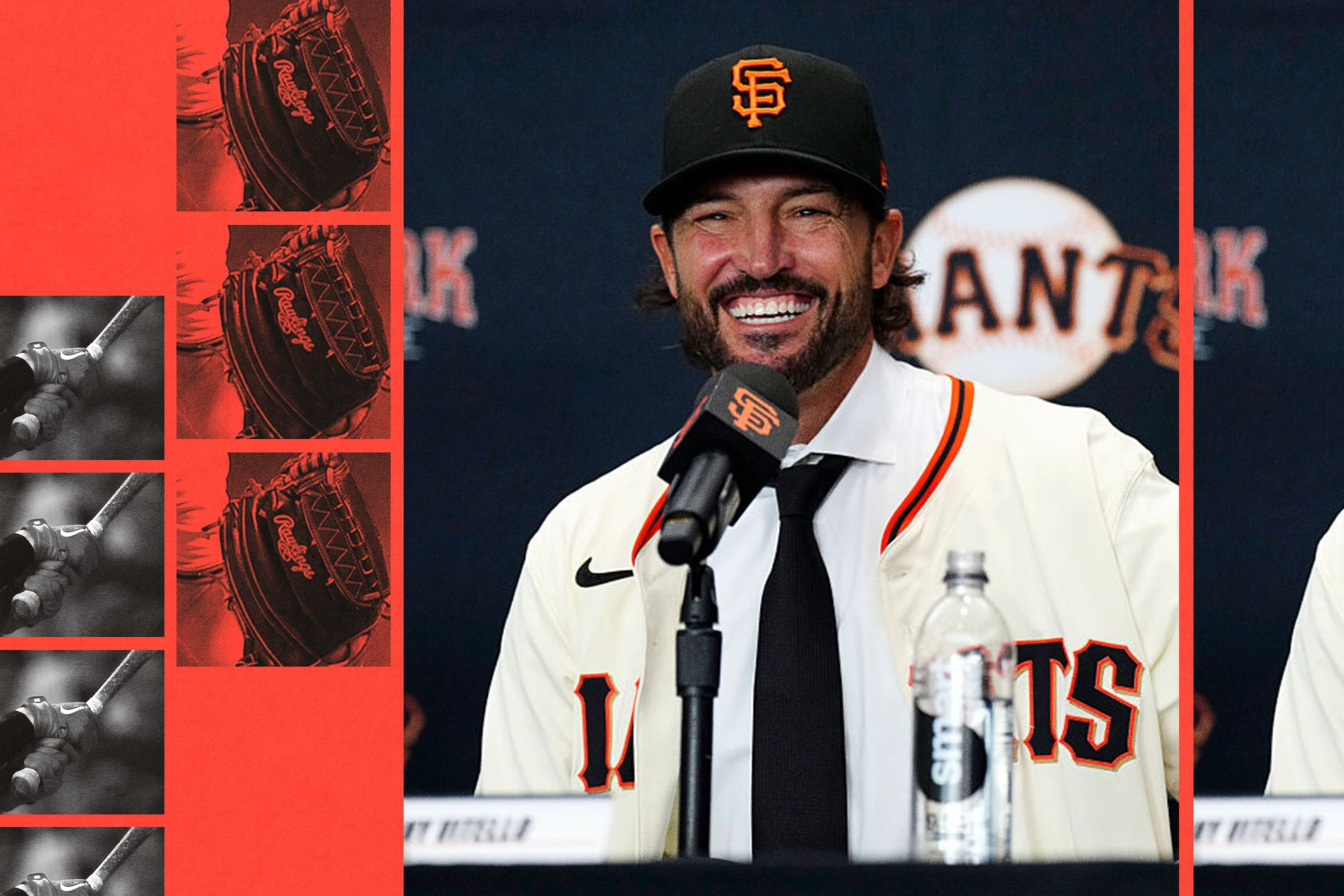

“It’s notoriously easy to build ballparks in Oakland,” Freedman said with a laugh. “It's well known to be the easiest place to do it.”

Freedman said it took four Park and Recreation Council meetings, two City Council meetings, two conditional-use permits, a major building permit, and of course, extensive periods of public comment to construct the 4,000-seat ballpark.

“Every single time there was an opportunity for community members to say they were supportive or they were against it, they called in and wrote in and said this is exactly what the community needs,” Freedman said.

At the very least, it’s exactly what Millikan needed. He wasn’t initially a candidate for the Ballers’ 2025 roster, but after a pitcher was sidelined with an injury, the team replied to his cold email.

“They set up a meeting, and they were like, ‘Can you pitch Sunday in Ogden?’” Millikan recalled. “And I was like, ‘Sure, I guess.’ So I flew out to Ogden, Utah, and met up with the team, and then the rest is history.”

Since joining the club after graduation, Millikan leads all Pioneer League pitchers who have thrown at least 80 innings with a 2.12 ERA. He’s one of four pitchers striking out more than 10 batters per nine innings and will enter the playoffs with a 22-inning scoreless streak.

The Ballers open the postseason Thursday at Raimondi Park, on the heels of a Pioneer League record for single-season wins. Their 73 regular-season victories shattered the previous high of 69, set by the Missoula PaddleHeads in 2022 in a league that’s existed since 1939.

A community baseball team

Ballers Manager Aaron Miles is the first to acknowledge that the caliber of the product isn’t the point.

“There are guys in this league that are throwing 100 mph,” said Miles, who spent parts of nine seasons as a utility man in the big leagues. “But if they’re in this league throwing 100, that means they can’t throw strikes, because they would be in affiliated baseball.”

At the Coliseum, the A’s hosted the Yankees, the Dodgers, and the Giants. At Raimondi Park, the Ballers play the Idaho Falls Chukars, the Grand Junction Jackalopes, and the Yuba-Sutter High Wheelers.

After the Warriors departed for San Francisco, the Raiders left for Las Vegas, and the A’s took a detour to Sacramento while they wait for a Sin City stadium, the pro sports world had abandoned Oakland. The Roots, a minor league soccer team founded in 2018, offered a vision of hope. To Freedman, the Ballers represented a new way to reach fans.

“Baseball is a better conduit for community engagement than any other American sport,” Freedman said. “And so part of our ethos is to bring the Oakland community, and bring the East Bay community together.”

The Ballers averaged a crowd of 2,300 for home games this season, but the people who show up are remarkably invested. Miles estimates around 500 hardcore fans attend three to four games per week, and Freedman credits a dedicated marketing team that works to engage various community groups on a nightly basis.

During an August homestand, the Ballers hosted Oakland Symphony Night, Cal Day, a Pride Night, and Día De Los Ballers. After major league games, players disappear into a clubhouse. After Ballers games, players walk through the stands and sign autographs.

“The fans feel that they know the players,” Miles said. “You’re signing autographs every single day after the game, before the game; you walk in through the crowd. It’s a beautiful thing.”

Keeping a dream alive

Miles, an East Bay native, went straight into pro ball after the Houston Astros selected him in the 19th round of the 1995 draft out of Antioch High. He rattles off the names of his favorite players he watched as a kid at the Coliseum – Mark McGwire, Jose Canseco, Tony Phillips – but his favorite connection from the teams that won three consecutive American League pennants and the 1989 World Series is manager Tony La Russa.

Miles played for La Russa in St. Louis, where he won a World Series with the Cardinals in 2006. He remembers standing in the dugout at Busch Stadium, plotting each strategic decision La Russa might make so Miles, a bench player, could prepare to pinch hit.

The man who brought Oakland its last title inspired Miles to manage.

“When I first heard about the team here, I just immediately said I want to be involved,” Miles said. “First, because it’s in my backyard, and then, because it’s professional baseball.”

The duties extend beyond the dugout, as Miles works alongside former major league players and manager and Ballers vice president Don Wakamatsu and assistant general manager Tyler Petersen to build out the roster. Last offseason, the group made thousands of phone calls, recruiting prospective players to continue their careers in Oakland. Miles estimates that 1 in 10 players answers or calls back, and some potential deals fall through when 22-year-olds choose a more traditional job over playing independent league baseball.

All the rejection leads to a funny phenomenon.

The players who do sign with the Ballers are some of the most intense, diehard, and competitive left in the sport. You have to really love baseball to spend every Monday during the summer taking multiple flights and then a bus ride to small towns in the western United States.

“This is the baseball dream,” said San Jose native and Cal product Luke Short. “You can’t really ask for more. You get paid to play. There’s fans that love our team and come out and see us every day of the week.”

Short, who was 7-1 with a 3.58 ERA this season, is one of about a dozen Ballers players with local ties. The left-hander attended Los Gatos High, idolized Madison Bumgarner, and said the phone call from Miles was the only one he received about continuing his career beyond college.

It’s possible no Ballers player has as many local ties as Gabe Tanner, a righty with a 3.26 ERA. The Danville native played at San Ramon Valley High and started his college career at Chabot College. After transferring to Cal State East Bay, where he pitched for three seasons, he showed up for a Ballers tryout in the spring and hasn’t left since.

It doesn’t hurt that Tanner’s presence has boosted ticket sales.

“My parents, I’m not even pitching and they’re coming,” Tanner said. “Some of my former teammates come out, and it’s awesome. The support I have is unmatched.”

The road ahead

The Pioneer League isn’t exactly a pipeline into the minors, but it’s a place where overlooked players can continue auditioning for opportunities and undervalued prospects arrive for a second chance.

In their inaugural season, the Ballers had three players sign with major league organizations, which can serve as a compelling way to recruit more talent.

Despite breaking win records this season, the Ballers haven’t had anyone depart for an MLB affiliate, but that doesn’t define their success. This franchise, still in its infancy, looks at what’s happening in the stands as much as what’s taking place on the field for validation.

When Freedman sees groups of friends arrive at Raimondi Park, he’s reminded of the feeling he experienced after moving from Chicago to Oakland after college.

“I came in, I was from a different city, and I was lonely,” Freedman said. “It was a circle of friends that was bonded around sports and around the A’s in particular that kind of brought me in.”

If the Coliseum is vacant and the A’s are an afterthought, what would the Ballers tell people who think baseball in the East Bay is dead?

Freedman and many players pondered this question, with almost everyone saying something along the lines of “It’s not dead; it’s just different.”

Millikan, who cold emailed his way onto the roster, put it more bluntly.

“They’re wrong.”