Imagine if a behemoth and a colossus got married and had an even bigger baby.

That mythical megacreature will give you a sense of the scale of Compass’ pending $1.6 billion acquisition of fellow real estate brokerage giant Anywhere. You might not know Anywhere’s name, but you surely know its brands, which include Coldwell Banker, Sotheby’s International, and Corcoran.

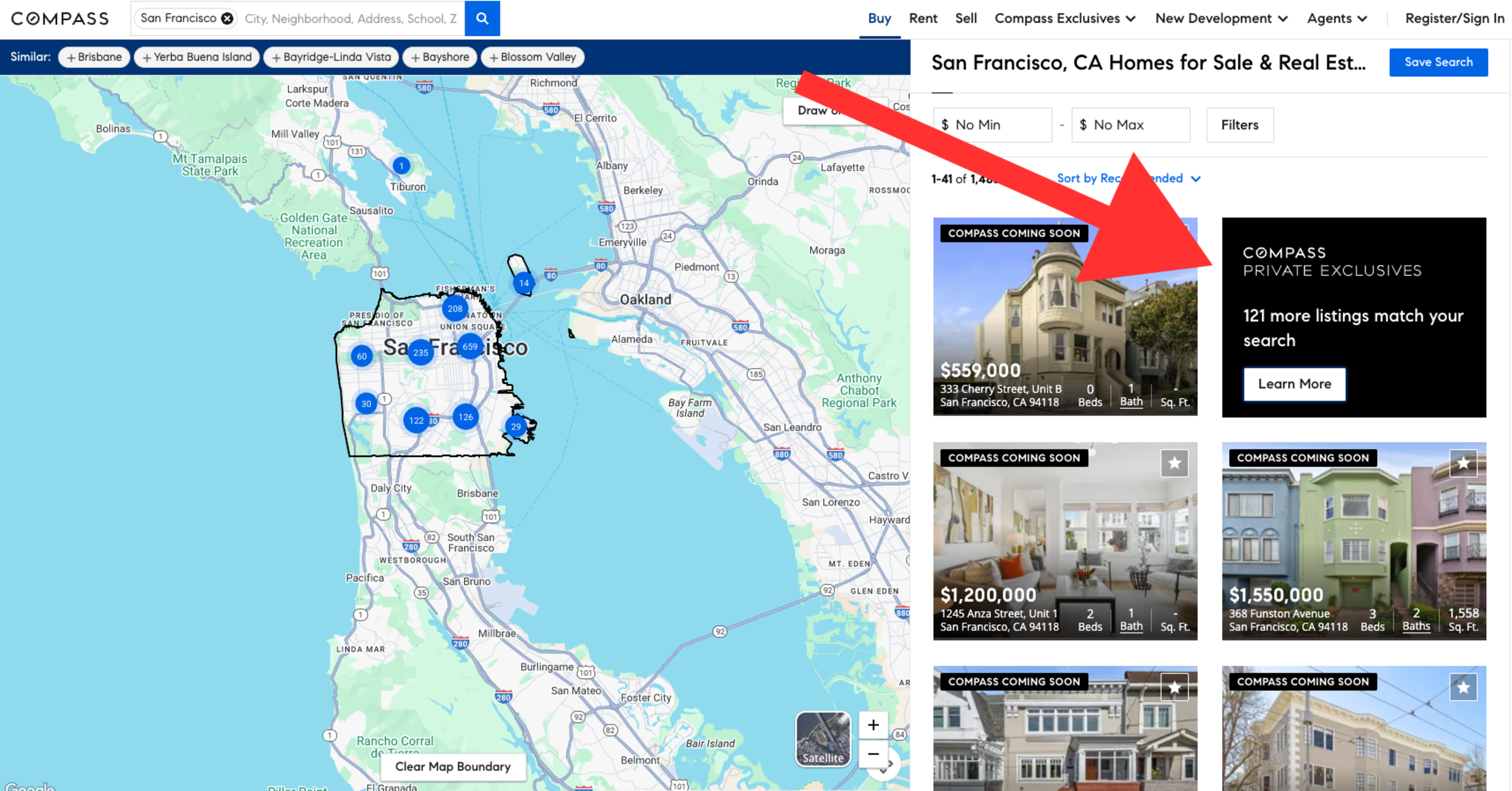

The combined value of the pending mega-corp is $10 billion, and the newly engorged Compass could create a near-monopoly in the Bay Area, making it the gatekeeper to thousands of exclusive listings, with Compass agents the only ones who could swipe the all-access pass. That means if you’re a buyer or a seller, Compass could become either your fairy godmother, with the power to grant your home ownership dreams, or the godfather with an offer you can’t refuse.

“I hope Compass isn’t trying to create a closed system,” Vantage Realty owner Mary Macpherson recalled thinking when she heard the acquisition news. “Protect the MLS at all costs, because that shared database really is the key to everything.”

Macpherson isn’t alone in worrying about the sanctity of the multiple listing service, which includes all homes marketed for sale and broadly shares its data with Redfin, Zillow, and other real estate sites. While “pocket listings” exist outside the MLS system, many smaller brokers worry that Compass could massively expand its controversial private listing practice and leave them out in the cold.

For DJ Grubb, president of East Bay-based The Grubb Company, the tactic also risks alienating buyers who want to see everything on offer — not just “Compass exclusives” — and sellers who want to put their homes in front of as many people as possible. No open market means “that seller didn’t get the benefit of a thousand eyeballs,” he said.

A battle over private listings

Compass’ local leaders declined to comment on the direct impact of the deal for Bay Area buyers and sellers. The company has so far only touted the combined entity’s reach and access to top-tier technology.

Founder and CEO Robert Reffkin said in a statement that Compass will preserve the “unique independence of Anywhere’s leading brands.” If that’s true, it means Sotheby’s and Coldwell agents won’t become Compass agents overnight — but time will tell.

Regarding Compass’ private listings site, Private Exclusives, Reffkin has argued that real estate companies have a right to keep listings among themselves for a longer period of time.

For months, he has fought Zillow in court and on social media over its rule blocking homes that were private listings for more than one day from its platform. (Zillow also blocks agents who repeatedly are found guilty of flouting that rule.) He accused the Seattle-based company of monopoly tactics and offered to share Compass’ listings if Zillow stops its ban on Compass agents who use private listings from its site.

Compass has also challenged the National Association of Realtors over its 24-hour Clear Cooperation Policy, which requires a broker to submit a listing to the MLS within one business day of publicly marketing it. In April, NAR upheld the rule but allowed an exception for office-exclusive listings not marketed publicly; for example, those advertised with only a “for sale” sign.

Reffkin wasn’t satisfied. In a July letter, he told NAR leaders that Compass doesn’t see the policy as binding and won’t automatically follow it, though it may comply with local MLS rules on a case-by-case basis.

Staying alive and independent

Compass’ promise of independence for its newly acquired brands runs contrary to its track record. When it purchased Bay Area shops Paragon and Pacific Union in 2018, they were quickly rebranded under the Compass empire.

Those buys turned the company into the 800-pound gorilla of Bay Area residential real estate. Compass agents logged more than $27 billion in local sales in the 12 months ending in May, according to data from The Real Deal, versus $15 billion in sales for No. 2 Coldwell Banker.

Terry Meyers, cofounder and president of Intero, which was third by sales volume, has seen his fair share of mergers and acquisitions over four decades in real estate.

He said the Compass deal makes sense from a business perspective, given that Anywhere was weighed down with debt and looking for an exit strategy, while Compass is still striving for profitability and saw money-making opportunities through its rival’s mortgage and insurance partnerships.

“They don’t have to reinvent the wheel,” he said of the newly enlarged Compass.

But there’s opportunity in being nimble and providing an option different from the status quo. Meyers launched Intero in 2002 after his previous firm was gobbled up by the company that would become Anywhere. He learned that agents and clients were thirsty for choice and a return to the independent days of old.

“They got a little uncomfortable, and there’s nowhere else to go,” he said of agents at the time. “That overflowed to the consumer as well.”

Clients may notice a change to the customer experience under the Compass/Anywhere merger. Grubb likened it to going from having a personal relationship with a teller at your neighborhood bank branch to calling the company’s 1-800 number for service.

He argued that the acquisition exposes exactly what Compass has become: the Walmart of real estate. “They’re a big-box store. They want to be a giant company. They’re still agent-centric, not client- and community-centric, and now we can just basically pitch against them,” he said.

Macpherson was a Paragon agent who got pulled into Compass in 2018 but left a few years later for Side, a white-label brokerage that helps with branding and runs back-end administrative and compliance functions.

“We felt that boutique love again, that I missed from Paragon. I thought, ‘OK, I’m making a switch,” she said.

Private listings, public problem

When Paragon first came under Compass’ wing, MacPherson said, Reffkin told her and others concerned about keeping the MLS open and collaborative that nothing would change. But that strategy has clearly evolved.

She noted that Compass’ tactics aren’t new — they simply formalize what brokerages and groups like Top Agent Network have long done: alerting their own members about upcoming listings to line up buyers quickly. This in-house approach appeals to privacy-minded sellers but often means sacrificing the best price or terms, and it has never been carried out at the scale of Private Exclusives.

“They just have so many more people in their system,” she said.

Although many listings aren’t included on Compass’ private network, some independent brokers have concerns that consumers may feel compelled to work with the agency because it appears to be the only option.

“From a leverage standpoint, when you can say that you have 25% of the real estate community in your organization, there’s a lot of weight behind that,” Meyers said.

He believes that most consumers want all properties on the MLS syndicated to Zillow and similar sites. But he’s willing to be proved wrong and believes that the customer is always right.

Intero is ready to push the button on publishing its own version of Private Exclusives — once it sees how the “aggravation” between Compass and Zillow plays out.

“We’re fine with letting everybody else fight the battle,” he said, “and then when the dust settles and we know what the consumer wants, we’ll give them that.”