A former San Francisco department head, now at the center of a city scandal, was paid by a nonprofit within months of signing a six-figure contract for the organization, in a possible violation of state law.

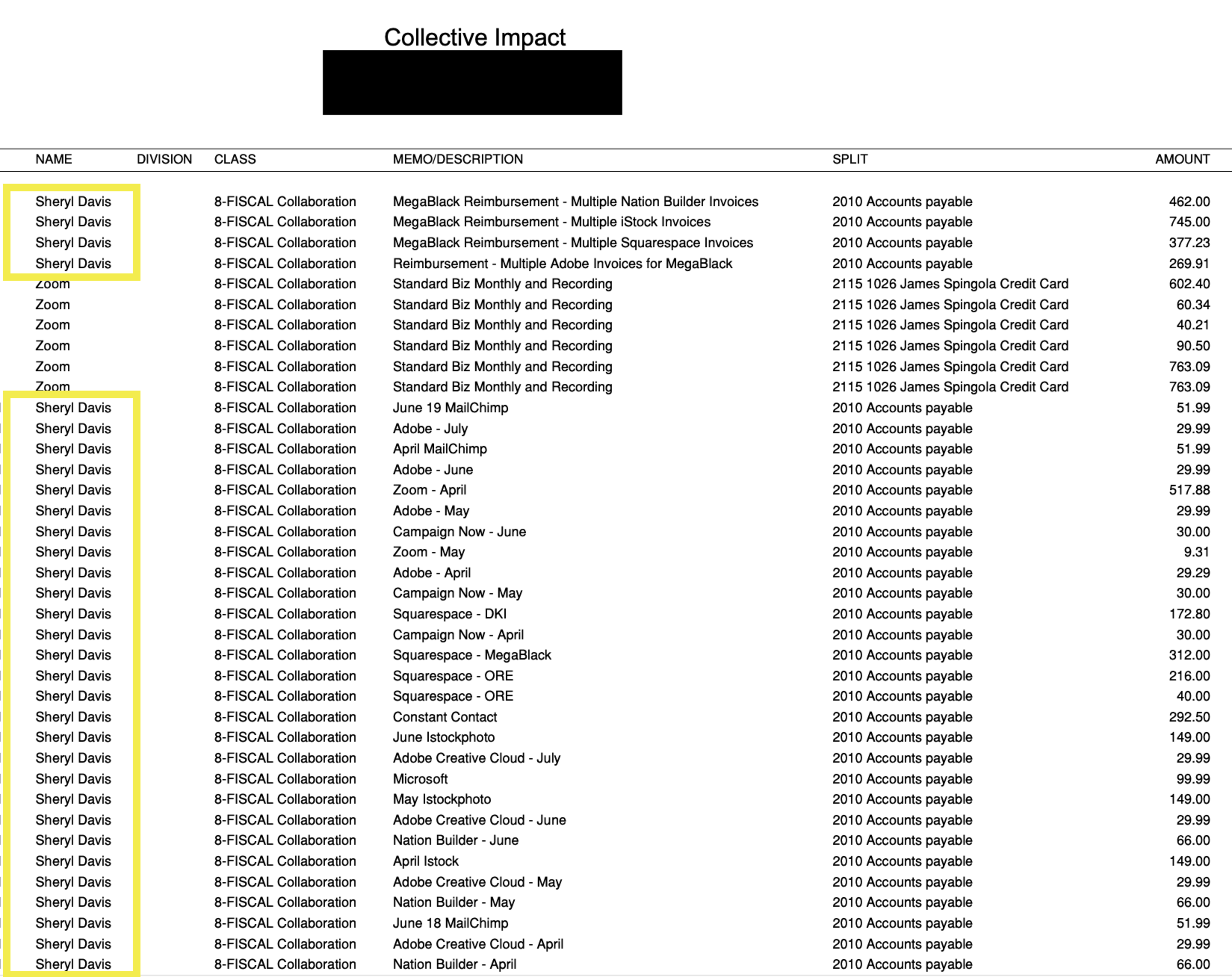

Sheryl Davis, who led the city’s Human Rights Commission until her September resignation (opens in new tab), received the payments in 2021 from the nonprofit Collective Impact, according to internal financial documents obtained by The Standard.

Davis signed off on funding totaling $1.5 million for the group, which is led by James Spingola, with whom she shared a home.

The revelation is the latest twist in a burgeoning City Hall scandal that has put Mayor London Breed’s flagship program for the Black community, the Dream Keeper Initiative (opens in new tab), under the microscope over allegations of misspending and a swirl of ethical questions. The documents obtained by The Standard are the latest example of potential misconduct at the center of a growing city probe — and represent the first evidence of money flowing from a Dream Keeper recipient to a city official.

In 2021, Davis received $5,179 in payments from Collective Impact, the documents show. The payments were marked as reimbursements for software subscriptions and other expenses, including items from the hardware store Lowe’s. State ethics law (opens in new tab), which treats reimbursements as a form of income, prohibits officials from making decisions involving entities from which they received (opens in new tab) income of more than $500.

“It’s fair to say that these payments raise red flags,” said Sean McMorris, an ethics expert from the government transparency nonprofit Common Cause.

One set of payments came three months before Davis signed a $575,000 contract for Collective Impact, and the second set came about six weeks after.

Davis’ attorney Tony Brass acknowledged that his client received payments from Collective Impact, adding that his client did not believe that the reimbursements she received counted as income.

Davis was Collective Impact’s executive director before leaving in 2016 for her city job.

“If it was negligence, then she should explain that. If she doesn’t think anything is wrong, then she should explain that,” said McMorris. “If it is willful intent, then the prosecution and penalties would be much higher. … On its face, I don’t see how it doesn’t apply to the conflict-of-interest code.”

Brass said the payments Davis received from Collective Impact stemmed from advocacy work she did for MegaBlack, an informal group that discusses issues affecting San Francisco’s Black community. Collective Impact was MegaBlack’s fiscal sponsor, the attorney said.

Davis was a private consultant for MegaBlack, Brass noted, adding that the work was outside of her role as head of the Human Rights Commission. She coordinated with a private firm to work on MegaBlack’s website and social media. Requests for comment sent to MegaBlack were not returned.

“She has been very candid about everything that happened during her time at HRC,” Brass said.

The Human Rights Commission, the mayor’s office, and the controller’s office declined to answer questions about The Standard’s findings, citing ongoing investigations. Spingola and other members of Collective Impact’s staff and board did not reply to a list of questions.

In another sign of close entanglements between Davis and Collective Impact, the nonprofit maintained a credit card in Davis’ name from at least September 2020 to March 2024.

Brass said Davis had not used the card since leaving the organization in 2016.

In addition to her position at the Human Rights Commission, Davis was a lead decision maker for the Dream Keeper Initiative. Breed launched Dream Keeper in collaboration with Supervisor Shamann Walton and other city leaders in July 2020 to redirect funds to economic and cultural development in Black communities.

Since then, city leaders have budgeted nearly $300 million for the program, and about $140 million has been spent, according to the controller’s office.

After The Standard revealed close personal ties between Davis and Spingola, and a San Francisco Chronicle story (opens in new tab) exposed problematic financial management at the Human Rights Commission, Breed asked Davis to resign.

With scrutiny of the program growing, Breed has paused Dream Keeper Initiative funds, and the city has launched a series of audits of the Human Rights Commission.

Spingola continues to lead Collective Impact and is still a commissioner on the San Francisco Juvenile Probation Commission.

MegaBlack, the group tied to the payments Davis received from Collective Impact, describes itself as “fighting for visibility, sovereignty, dignity and justice for Black San Franciscans.” Its website does not list its members but says the group has helped draft local legislation, advocated for reparations, and hosted cultural and culinary events.

MegaBlack coordinated a rally last month decrying media coverage of the Dream Keeper Initiative as unfair attacks on an essential program for the Black community.