When news broke last week that Wells Fargo was planning to vacate its longtime headquarters at 420 Montgomery St. as part of a broader shift away from the West Coast, some observers saw the move as a betrayal of San Francisco — the city with which the financial services behemoth has been intertwined since the Gold Rush.

In fact, the company is only moving six blocks away, to 333 Market St. While that’s hardly tantamount to ditching downtown, one thing won’t be packed into the proverbial U-Haul: the two-story Wells Fargo Museum (opens in new tab). It’s a curio cabinet of old-timey arcana, from lithographic stock certificates to a reproduction of the very first check cashed in the fledgling United States — and it will all go away, a company representative confirmed to The Standard.

“The museum will close by the end of the first quarter of 2025,” Wells Fargo spokesperson Edith Robles said. “We will have additional information in the coming months.”

When The Standard visited Friday, we found an endearingly corny collection full of sepia and fake gold nuggets. Sure, most of the interactive exhibits are inoperative — don’t bother posing for the camera that purports to put your face on a dollar bill — and there’s nary a mention of the company’s century-plus of juicy scandals, from redlining and nonconsensual credit cards to this year’s incident in which a dozen employees were terminated for faking work through simulated keyboard activity (opens in new tab). But for anyone who isn’t totally put off by big Manifest Destiny vibes, there are tidbits galore.

Visitors can inspect a “dotchin,” or portable scale that Chinese miners used for measuring tiny quantities of gold, pore over blown-up sections of photographer Eadward Muybridge’s 1877 panorama of the doomed city’s skyline, and discover that Lake Tahoe was once called “Lake Bigler.”

And yes, you can climb into a genuine Wells Fargo stagecoach, as if auditioning for a role in “The Music Man.” Technological marvels of their day, they were dark and cramped, with hapless passengers occasionally relegated to the roof.

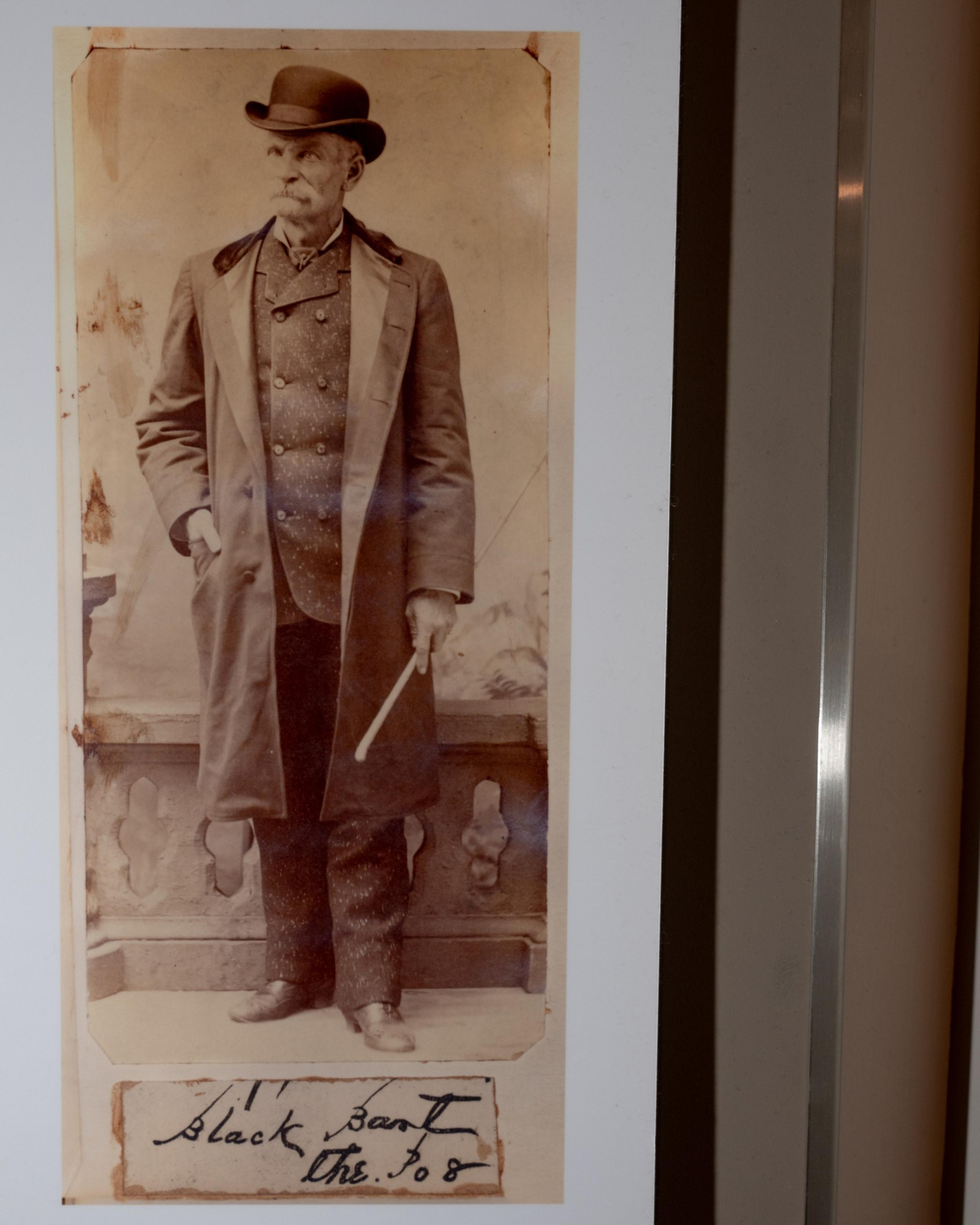

Wells Fargo’s history parallels that of California, if not the entire western United States. From the day in 1852 when Henry Wells shook William G. Fargo’s hand, the company was never simply a bank; it was a delivery service, communications firm, and precious metals broker, too. Its armed agents pursued stagecoach robbers with ruthless efficiency, including one “Black Bart,” a so-called gentleman bandit who taunted his pursuers with handwritten poems. It absorbed the Pony Express, the 1860s equivalent of a flashy startup, once the telegraph’s arrival undercut the financial feasibility of couriering mail by horseback.

The museum is open only on weekdays, and admission is free. It feels suited for elementary school field trips, but when we visited there were no children learning about telegraphs and rotary telephones (equally archaic devices, from Generation Alpha’s point of view). There wasn’t much of anybody, really — only two curiosity-seekers wandered in during their lunch hour. Two employees were only too happy to expound on the wisdom of leaving bank vaults to cool for weeks after the 1906 earthquake and fire. But they would not say what’s going to happen to all this stuff when the place closes in approximately 90 days.

While Wells Fargo isn’t turning its back on San Francisco like Del Monte Foods, Bank of America, and the Transamerica Corporation — iconic companies that all moved away decades ago — its decision to vacate 420 Montgomery speaks to the fact that everything’s about money in the end. As Black Bart versified in his catch-me-if-you-can doggerel, “I’ve labored long and hard for bread, for honor, and for riches. / But on my corns too long you’ve tread, you fine-haired sons of bitches.”