For years, the Pretrial Diversion Project (opens in new tab)—a nonprofit that provides alternatives to jail for criminal offenders in San Francisco—has touted an exemplary success rate in keeping clients out of trouble.

A new report suggests that the agency’s stated track record may not paint the whole picture.

The Pretrial Diversion Project (SFPDP), which has contracted with the San Francisco’s Sheriff’s Department since 1976, says that outcomes from its diversion programs—which range from specialized “neighborhood courts” to street-cleaning projects in lieu of fines—meet and exceed national standards. For 2020, the nonprofit reported that approximately 90% of its clients did not reoffend, and that 76% made all required court appearances, while enrolled in its programs.

But those statistics do not reflect SFPDP’s overall performance, according to District 2 Supervisor Catherine Stefani. At a Board of Supervisors meeting on Tuesday, she said the nonprofit, which receives millions per year from the city, had withheld more detailed information from Supervisors in advance of a contract renewal.

“It’s extremely misleading and dangerous to not provide the entire picture,” said Stefani. “I want to be very clear about this: This is not to say that the goals of pretrial diversion are unworthy. Of course they are [worthy]. But we need to know what is working and what is not, and what needs to be done better, to keep the public safe and to help their clients succeed.”

The 90% “safety” rate that SFPDP provides—meaning the person did not reoffend—includes a few caveats.

The rating only includes cases with a new filed charge, rather than new arrests, and only includes new filings within San Francisco. The rates are updated on a quarterly basis, but because the pretrial period can last much longer than three months, they may not necessarily account for a client’s behavior throughout the entire cycle of a case.

“I’ve been asking for information about the success of individuals during the entire lifecycle of the pretrial release for awhile now,” said Stefani, who was the only supervisor to vote against an extension of SFPDP’s contract with the city last month. “It is unacceptable for a contractor in any capacity to come to this body and request tens of millions of dollars in taxpayer money, while knowingly withholding critical information.”

In addition to running diversion programs, SFPDP administers risk assessments for roughly 6,500 criminal defendants per year in San Francisco. Those assessments are automated using an algorithm called the Public Safety Assessment (PSA), which issues a risk score, a prediction of how likely the person is to reoffend and show up to court dates, and a recommendation on whether the person should be detained.

A separate study of the PSA (opens in new tab) published this month by the California Policy Lab, an independent research center at UC Berkeley that conducts research for SFPDP and other agencies, suggests much worse outcomes in diversion cases.

Looking at cases between 2016 and 2019, the study found that 55% of defendants were rearrested—either in San Francisco or in other jurisdictions in California—during the pretrial period, and that riskier defendants were more likely to be rearrested. California Policy Lab observed that by this measure, San Francisco’s safety rate was “substantially lower” than rates in other jurisdictions using the algorithm.

The Board of Supervisors recently rubber-stamped a $18.7 million, three-year contract with SFPDP to extend its assessment and diversion services, which typically begin after a criminal defendant is booked.

Prior to arraignment, the PSA algorithm analyzes the defendant’s age, history and other factors, and spits out a recommendation. Along with input from the District Attorney and defense attorneys, a judge may elect to release that person on their “own recognizance,” which comes with minimal supervision. Defendants deemed to have higher needs may be referred to “assertive case management,” which comes with more frequent check-ins and referrals to other diversion programs.

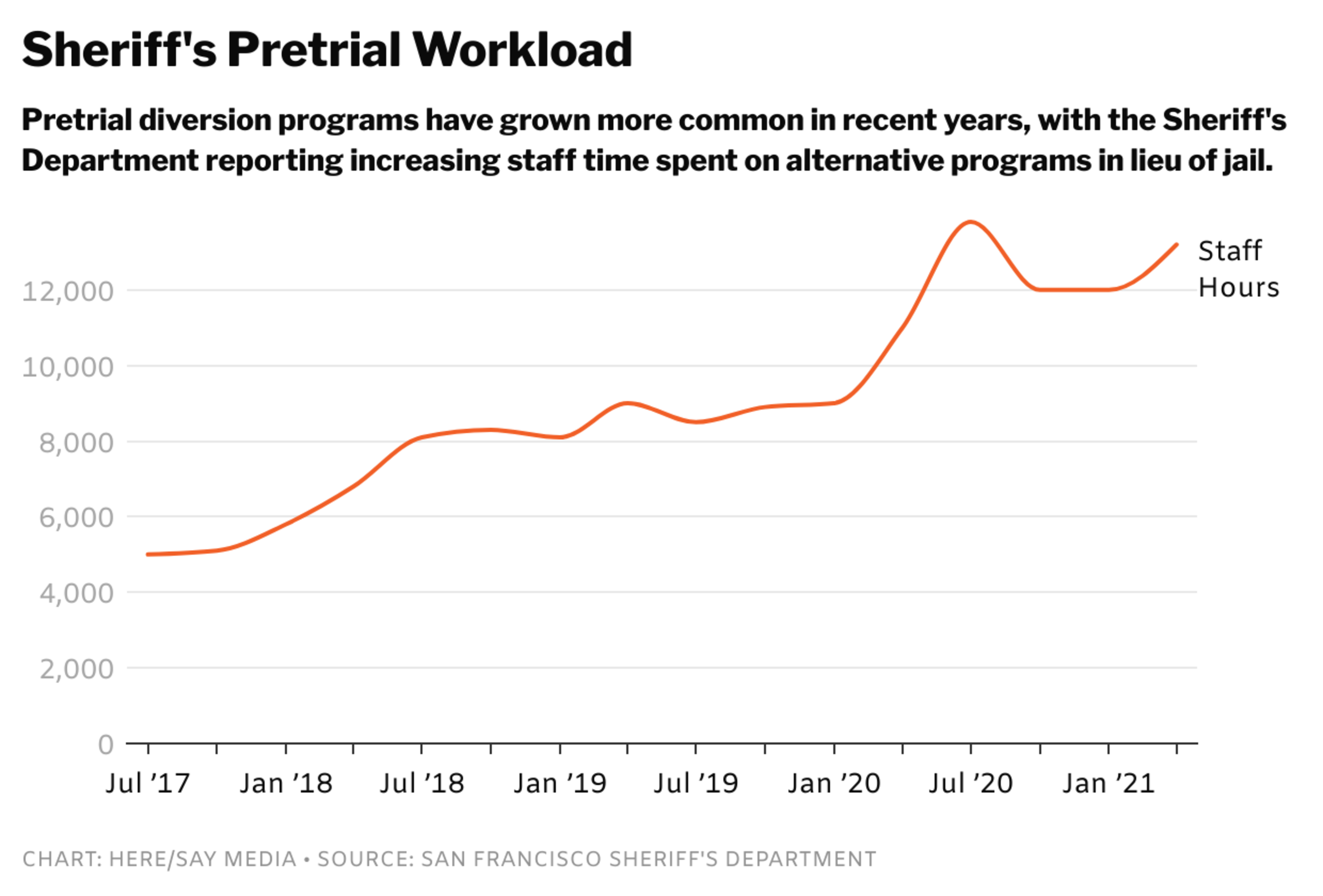

San Francisco courts have relied more heavily on pretrial diversion, rather than traditional court proceedings, in recent years.

According to the Sheriff’s Department, there were 796 individuals on pretrial release and in alternative sentencing as of June 2016. By June 2021, that number had grown to 1,829, equivalent to 69% of individuals who were booked for a crime. Two court decisions in 2018 and 2019, referred to as the Humphrey and Buffin decisions, placed stricter conditions on pretrial detention and increased reliance on diversion programs.

Johanna Lacoe, a research director at the California Policy Lab, emphasized that the new study was not intended as an evaluation of pretrial diversion, but rather as an evaluation of how well the algorithm is working. One can’t make an “apples to apples” comparison between the 55% rearrest rate and the 90% safety rating publicized by SFPDP, she said.

Neither SFPDP nor its CEO, David Mauroff, responded to requests for comment by press time.

In a March letter, Mauroff told Stefani that its current statistics conform with the meeting cadence of a work group, composed of representatives from the Sheriff’s Department, the District Attorney’s Office, the Public Defender’s Office and other stakeholders, that meets quarterly to assess the performance of pretrial clients.

Nonetheless, the jarring rearrest statistics in the new report underscore a need for greater transparency on diversion programs, according to Stefani.

The District 2 supervisor called on the San Francisco City Attorney to draft legislation that would require much more detailed disclosure of pretrial outcomes, including out-of-county offenses, reporting that covers the entire pretrial period, and information on how often judges followed the algorithmic risk assessments.

In San Francisco, a string of high-profile crimes in which a defendant was found to have several recent arrests has raised questions around the court’s duties to both defendants and the public at large.

Stefani emphasized that judges, and not the Sheriff’s Department of SFPDP, ultimately make the decision on whether a defendant should be diverted into a program or detained. But she asserted that SFPDP has had access to the more detailed statistics at least since March 2021— when the new study was drafted—but did not disclose the information to the Board of Supervisors ahead of its new $18.7 million contract agreement with the city.

“They acted like it didn’t exist,” she said.