For the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Monday’s solar eclipse is like Christmas, Outside Lands and the Olympics all rolled into one.

The 135-year-old organization housed in an unassuming building on Ingleside’s Ocean Avenue has been preparing for this for three years: arranging a star speaking lineup, ordering merch, dispatching news alerts and snapping up plane tickets.

“These are wondrous events,” said Astronomical Society educator Shanil Virani, “and a way of connecting with our shared cultural heritage and the sense of wonder our ancestors had.”

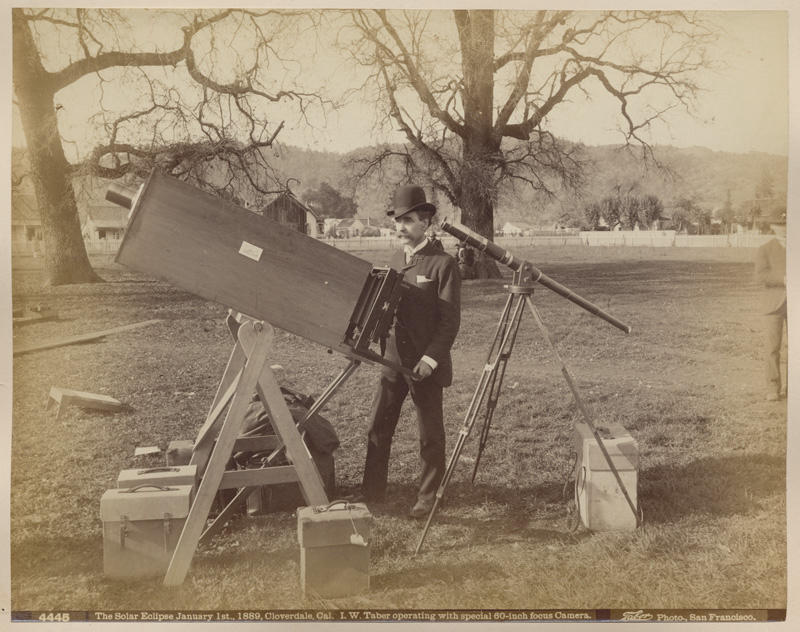

The coming eclipse harkens back to the organization’s roots, which was founded in 1889 after a group of amateur astronomers gathered in downtown San Francisco in the wake of a solar eclipse and didn’t want the fun to stop.

“Science literacy was founded on a solar eclipse that came through Northern California in the late 19th century,” said Virani, who was busy packing up Wednesday to travel to Junction, Texas, which is in the path of totality. “In some ways, it’s come full circle.”

More than a century later, the organization has grown into a far-reaching institution. It receives grant monies from NASA and the National Science Foundation, partners with organizations like SETI and the Exploratorium and had Carl Sagan on its board at one point. The coming solar eclipse, in turn, is a stellar event for raising awareness about the organization.

“It’s a big opportunity to get funding to do the work we do,” said Joycelin Craig, director of membership and communications.

The society launched two programs—eclipse “ambassadors” and eclipse “stars”—to mobilize an army of educators across the country. The ambassador program, in 47 states as well as the territories of Guam, Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C., had the goal of reaching 100,000 by E-Day. It’s already … eclipsed that number by a longshot.

The 700 ambassadors received eclipse kits to teach their audiences, boxes of educational materials staff members were furiously packing up a month ago in their Ocean Avenue offices to get into the mail.

The eclipse “stars” program is much smaller, at around 100 participants, and is geared toward high school teachers, graduate students and early career astronomy faculty who want to know best practices for communicating science to the general public.

It also creates materials in Braille for the blind, has sent eclipse glasses to prisons for the incarcerated on the path of totality (with funding from NASA) and has put together guides for understanding how different cultures across the world interpret the eclipse phenomenon differently: For the Cherokee, it’s a giant frog eating the sun; for the Euahlayi aboriginal people of Australia, it’s the sun and moon as lovers embracing in secret.

“It’s a reminder of how different cultures developed different understandings,” Virani said.

Craig attempted to describe the experience of an eclipse—especially one like this, which will have four full minutes of totality as opposed to the ninety seconds of it in the 2017 eclipse. In an instant, she said, the environment transforms: The air gets cooler, automatic lights turn on and the noises of animals change.

“It’s like a 360-degree sunset,” Craig said. “No matter where in the sky you look, you can see it.”

Members of the society’s staff, which number around 20, are crossing the country to chase the path of totality in a variety of states: Texas, New York, Arkansas, Ohio.

“It’s a little sad, too,” Virani said. “Because Monday represents the end of a program that has been a fantastic and enormous success.”