A fit Gen Z guy averages around 25 push-ups before hitting his limit, according to the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, while a similarly fit young woman can do around 15. But Dr. Dobri Kiprov, a 75-year-old longevity specialist from Marin, is easily crushing 50, he says — and we’re talking full military push-ups, not the knees-down version.

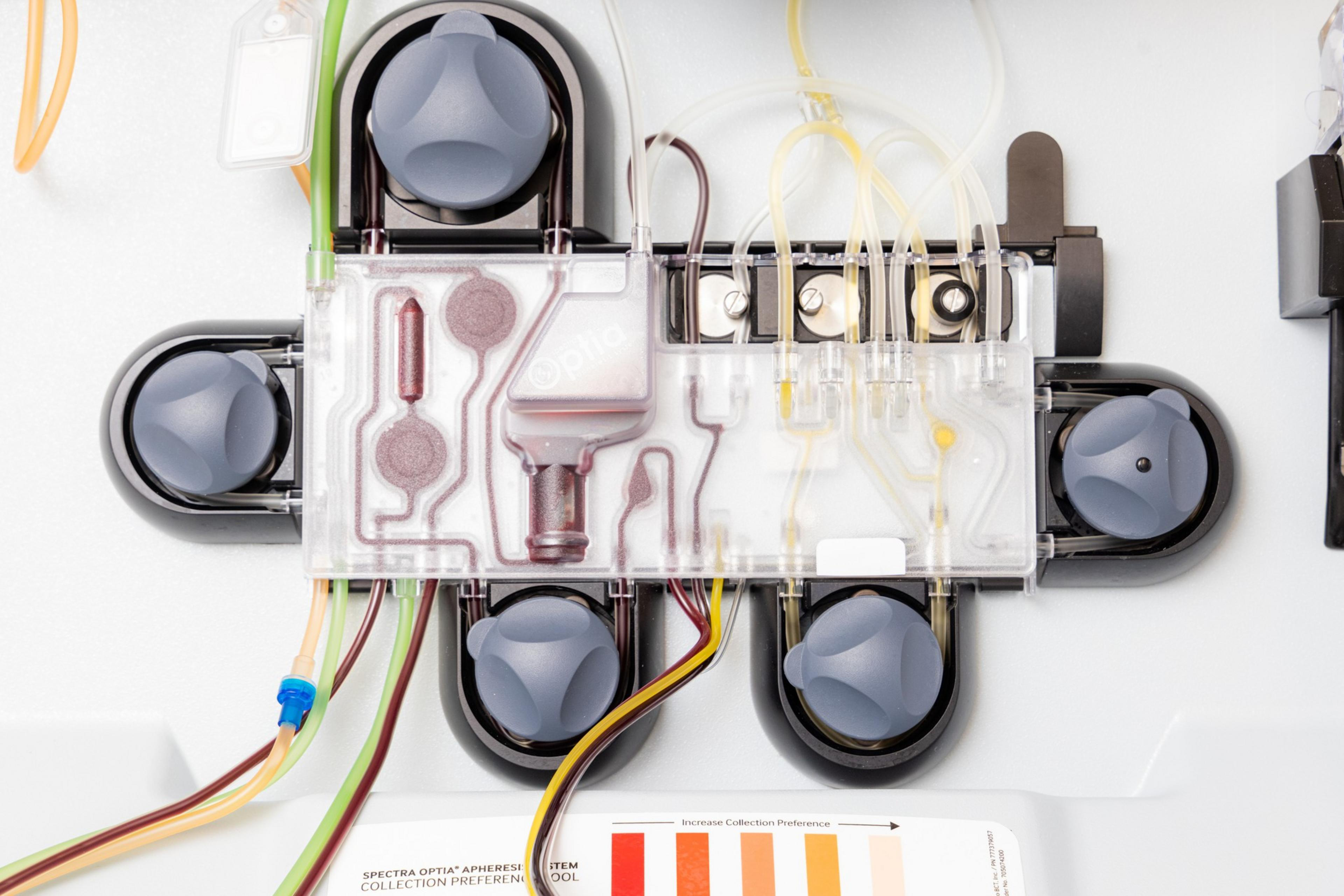

Kiprov, a Harvard-trained immunologist, credits his push-up prowess to a balanced diet, stern exercise routine, and every-other-month therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) treatments, in which two liters of blood are sucked from his veins into a dresser-size machine. From there, they’re whipped around by centrifuge to separate the plasma from the red blood cells. The plasma is piped into a clear plastic sack and discarded, and the other stuff — red and white blood cells and platelets — is combined with a solution of saline and albumin (the latter derived from purified human plasma), which is then pumped back into Kiprov’s body.

It’s like an oil change that extends the life of your automobile, or a thorough cleaning of a fishbowl. “If you have an aquarium and you don’t change the water, your fish will die,” he said. “But if you keep it clean and give them food, they’ll thrive. This is the same thing.”

Kiprov’s Mill Valley clinic Global Apheresis (opens in new tab) is the only Bay Area commercial provider of TPE for rejuvenation. (He also treats people of various ages for long Covid, Alzheimer’s, and multiple sclerosis.) He charges $6,000 per TPE treatment and recommends getting them every two months, to the tune of $36,000 a year. “I would like to offer it to everybody, but only 1% of the population can afford it,” he said.

Kiprov treats around 12 people a month; his TPE clients include longevity guru Peter Diamandis (opens in new tab); Lou Hawthorne, CEO of the biotech startup NaNotics; and an assortment of Silicon Valley venture capitalists and international longevity-seekers.

All of his TPE-for-longevity patients are over 50, but there’s been a surge of interest from millennials, he said, despite little data on rejuvenation benefits for that age group. “Bryan Johnson has sparked the idea of taking care of yourself as early as possible,” he said, referring to the tech exec turned cultish longevity hacker.

The average adult body contains around five liters of blood and 20,000 proteins. These proteins work in harmony while we’re young but become imbalanced over time, with an excess of plasma cytokines, for example, causing tissue and blood inflammation. TPE specifically extracts and junks plasma, diluting around 40% of “aged” plasma in the body, and has been found to reduce (opens in new tab) protein markers for neurodegeneration and cancer via molecular rejuvenation.

Silicon Valley’s all in on the hemoglobin hype train. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has invested $180 million (opens in new tab) in Retro Biosciences, a longevity-focused blood research company. Oracle co-founder Larry Ellison has reportedly thrown $330 million into various longevity ventures. And Alphabet co-founder Larry Page has pushed $1.5 billion into Calico, a longevity biotech startup. The anti-aging market is predicted to generate $421.4 billion in revenue by 2030, according to P&S Intelligence.

The interest of the tech industry’s moneyed class in blood biohacking can be traced to a much-cited Stanford study (opens in new tab) published in 2005. Building on research from the 1950s, scientists stitched together two mice — one young, one old — in a procedure called parabiosis: Think “The Human Centipede,” but for circulatory systems. The younger mouse’s blood rejuvenated the older one’s molecular signaling pathways, boosting muscle regeneration and even reversing liver damage.

The findings were a game changer, sparking a wave of blood rejuvenation startups — and countless internet jokes about aging billionaires vampirically siphoning the life force of young Blood Boys. Among the new startups was Elevian, which raised $40 million from investors like Diamandis to fund blood regeneration research. Then there was Ambrosia, a now-defunct startup that offered $8,000 infusions of young blood to clients over 35. Rumored to have attracted attention from Peter Thiel (and spoofed on HBO’s “Silicon Valley”), Ambrosia shut down after catching heat from the Food and Drug Administration.

Despite the FDA crackdown, some longevity clinics still sell fresh frozen plasma ($15,000 a liter (opens in new tab) at Everspan Life), something Kiprov strongly opposes. Young blood infusions carry many side effects, he stressed, presenting risks ranging from anaphylactic shock to death; he claims to know of two fatalities linked to young blood infusions.

Irina Conboy, a UC Berkeley bioengineering professor and co-founder of Generation Lab (opens in new tab), a startup that measures biological age, echoed Kiprov’s hesitancy. “There are zero benefits of using young blood. Zero,” she said; the FDA’s sterilizing procedures reportedly “extinguish” any potential youth factors.

Hence Kiprov’s shift to TPE. The reason? While the old mouse in the famed Stanford study did get younger, the young one actually got biologically older as proteins from the older one’s blood negatively affected its health.

This was a revelation, said Kiprov. In 2022, he conducted a placebo-controlled clinical study (opens in new tab), partly funded by Khosla Ventures and supported by the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, examining the anti-aging potential of TPE on patients mostly age 50 and up.

To track results, Kiprov measured participants’ biological age — which can be the same as chronological age but often differs based on genetics and lifestyle — using 33 DNA methylation tests. He also assessed mobility, flexibility, and grip strength.

He found that his patient’s epigenetic age dropped by 2.5 to 5 years. “It’s not dramatic,” he said, though some reported major improvements. “It was amazing for women with arthritis. After a few treatments, everything disappeared.”

Kiprov’s next frontier: a study on whether TPE can remove microplastics — the latest villain of the longevity community — from the blood. “As they accumulate, [microplastics] damage your body. If we can remove them, we can change the whole field of medicine,” he said. At Johnson’s Don’t Die Summit in September on Pier 35, the anti-aging guru gauged interest in a Blueprint-branded (opens in new tab)take-home microplastic testing kit; all 50 sold out.

Herbert Haas, a 72-year-old retired engineer and real estate mogul from Frankfurt, was part of Kiprov’s anti-aging study. TPE made Haas feel so refreshed that when the study concluded, he paid for additional treatments, flying to San Francisco every three months. “I dare to say I feel a little bit younger,” he said. “It’s a little bit like going back in time. I feel like I’m 64.”

In Kiprov’s Mill Valley office, just a block from a Ferrari dealership, I watched as plasma drained from Haas’ arm into a heavy plastic bag. The liquid was thick, sludgy, and an unsettling shade of yellow. Throughout the process, Haas reflexively squeezed a blue stress ball with his left hand — not out of pain, but to keep the blood flowing. “When I tell people, most shake their heads,” he admitted. “Even my wife thinks I’m crazy.”

TPE is FDA-approved for specific use cases, such as sickle cell anemia (opens in new tab), transplant failure, and multiple sclerosis, but off-label uses are legal. Kiprov has investigated non-longevity applications, such as treating OCD (opens in new tab) and tic disorders in children, addressing long Covid symptoms (he notes a 65% success rate, especially with early intervention), and a potential benefit for Alzheimer’s disease (opens in new tab).

‘Get rid of bloodletting’

There are, of course, doubts about the efficacy of Kiprov’s methods. Conboy, the bioengineering professor who co-authored the much-cited mouse study, warns strongly against many of TPE’s off-label uses. Despite co-authoring some of Kiprov’s research, she said some of his work is “very scary.”

“There are very limited studies, and people are applying it to everything. I disagree with using it on healthy people or on people with psychological problems,” she said. Conboy also warned of risks with repeated treatments aimed at anti-aging: “If you perform this procedure frequently enough to offset aging, side effects start to accumulate: kidney damage, liver damage, toxicity. Using other people’s antibodies [contained within the albumin solution] is not benign. If you’re healthy and want this to improve your tennis game or do cartwheels, then think twice.”

To tackle the paradox of anti-aging benefits that come with health risks, Conboy developed her own plasma replacement formula, patented by UC Berkeley, which is set to be published in 2025. She claims it provides the anti-aging benefits of TPE with just two infusions per year and contends that this is safer. But her real goal is to eliminate the need for longevity transfusions altogether.

“We need to get rid of bloodletting,” she said. As research continues to reveal how plasma dilution affects aging proteins, Conboy envisions developing molecules that could deliver the same benefits. “You’d start using them when you’re 45 or 50, so you’d grow old but also gradually become younger,” she said. “This will be the next generation of longevity therapeutics.”

Kiprov is open to innovation in his field but is less convinced of the timeline for change. In 2023, he partnered with Healthy Longevity, a Florida-based clinic, to bring TPE to Boca Raton (opens in new tab). “People are looking for the fountain of life,” he said. “They’ve spent hundreds of millions looking for magic pills because they want to be younger.”

For now, he’s content being the go-to blood guy in the Bay Area and beyond. “The idea is to die as young as possible, as late as possible,” he said.