San Francisco’s new police union president, Louis Wong, cuts the figure of a cop’s cop.

Burly, pugnacious, and with a shaved head, he spent 30 years walking some of the city’s meanest streets, from the Tenderloin to SoMa, chasing down suspects and uncovering caches of weapons and drugs.

That experience helped Wong earn 63% of the vote in July to become the first Asian American president of the San Francisco Police Officers Association, the union that represents the city’s roughly 1,300 regular officers. He won his campaign on the promise to push for better benefits, including higher pay and earlier retirement, when the union negotiates with City Hall on a new contract next year.

“He’s your quintessential boots-on-the-ground guy,” said Steve Ford, a former SFPD officer and Antioch police chief.

The POA president has traditionally served as the attack dog for the rank and file. Wong’s predecessor, Tracy McCray, who was ineligible to continue in that role after being promoted to commander, was known as much for her controversial antics (opens in new tab) as for member advocacy.

Wong ran as more of a pragmatist than a fire-breather. However, there’s little indication he plans to take the organization in a drastically new direction, current and former cops told The Standard. Some fear his endorsement by command staffers could hamper his independence.

Instead, he will be flexing a new swagger in the department, taking the reins amid a political shift among cops and the public that was best summed up by former Mayor London Breed: “Less tolerant of all the bullshit (opens in new tab).”

“I think that the dynamic in San Francisco politically has changed, and they also have changed at the POA,” former union president Tony Montoya (opens in new tab) said.

Public opinion shifts on policing

When Daniel Lurie was elected mayor in November, he promised to prioritize public safety. In office, he has emphasized the importance of hiring more police officers to crack down on the city’s stubborn drug crisis.

Wong, meanwhile, wants to further defang the Department of Police Accountability, an independent agency that investigates police misconduct, and put an end to the practice of allowing people to make anonymous complaints to the oversight group.

It’s a marked contrast from 2020, when the Black Lives Matter protests created an era of greater police scrutiny.

But while tough-on-crime police may be back in vogue, there are plenty of tricky waters for Wong to navigate; namely, a recent overtime abuse scandal that put a spotlight on the fact that the SFPD repeatedly blows its overtime budget (opens in new tab). Amid recent protests against U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the department spent $120,000 in overtime to patrol the demonstrations, records show.

Wong himself has benefited from overtime pay. He was among the highest-paid employees in 2022-23 (opens in new tab), raking in $465,000 — more than 70% of that from overtime pay.

Meanwhile, the union’s ranks are thinning due to retirements and lackluster recruitment.

Wong’s political balancing act

Wong’s 30 years on the force have not been without controversy.

He was named in a 1999 lawsuit in which two brothers (opens in new tab) claimed that officers beat them up, though it’s unclear how Wong was allegedly involved.

In 2002, Wong was named in another lawsuit after 10 officers shot and killed a man outside of the Metreon movie theater (opens in new tab). Wong has said he was not one of the shooters. That same year, two civilian women complained to the Department of Police Accountability that Wong called them “bitch”; Wong received no discipline.

Rather than red flags, many officers characterize such incidents as signs of a hardworking cop, and Wong enjoys widespread support in and outside the department. That goodwill is critically important as he has to split the difference in representing the rank and file and playing nice with department brass.

His backing from some in leadership have led to concerns about whether he is willing to go to the mat against his political benefactors. Former union president Montoya said POA leaders don’t usually win when command staff endorse them, as in Wong’s case.

“It can make it look like you are in bed with management,” he said.

Another former high-ranking officer told The Standard that Wong’s campaign promises appear more focused on achieving officer rewards than on promoting good policing. “The big concern is whether or not they will be working together to improve pay and benefits to the detriment of accomplishing the mission,” he said of relations between the union and management.

Wong’s rise is being celebrated in other quarters. Chinatown politicos are set to put on a party this fall to celebrate the union’s first Asian American leader.

Shelley Costantini, a Rincon Hill resident, was happy about Wong’s elevation to union leader but sad that he would no longer be walking the beat in her neighborhood.

“I could cry that he’s no longer part of the street,” said Costantini, adding that Wong was the rare officer who would “get into the nitty gritty of situations and deal with them, rolling their sleeves up.”

Rather than the busts he has made over his career, Wong said he’d like to be known for “30 years of human kindness.” There were the times he paid cab fare for people broke and stranded, or when he bought McDonald’s for those living on the street.

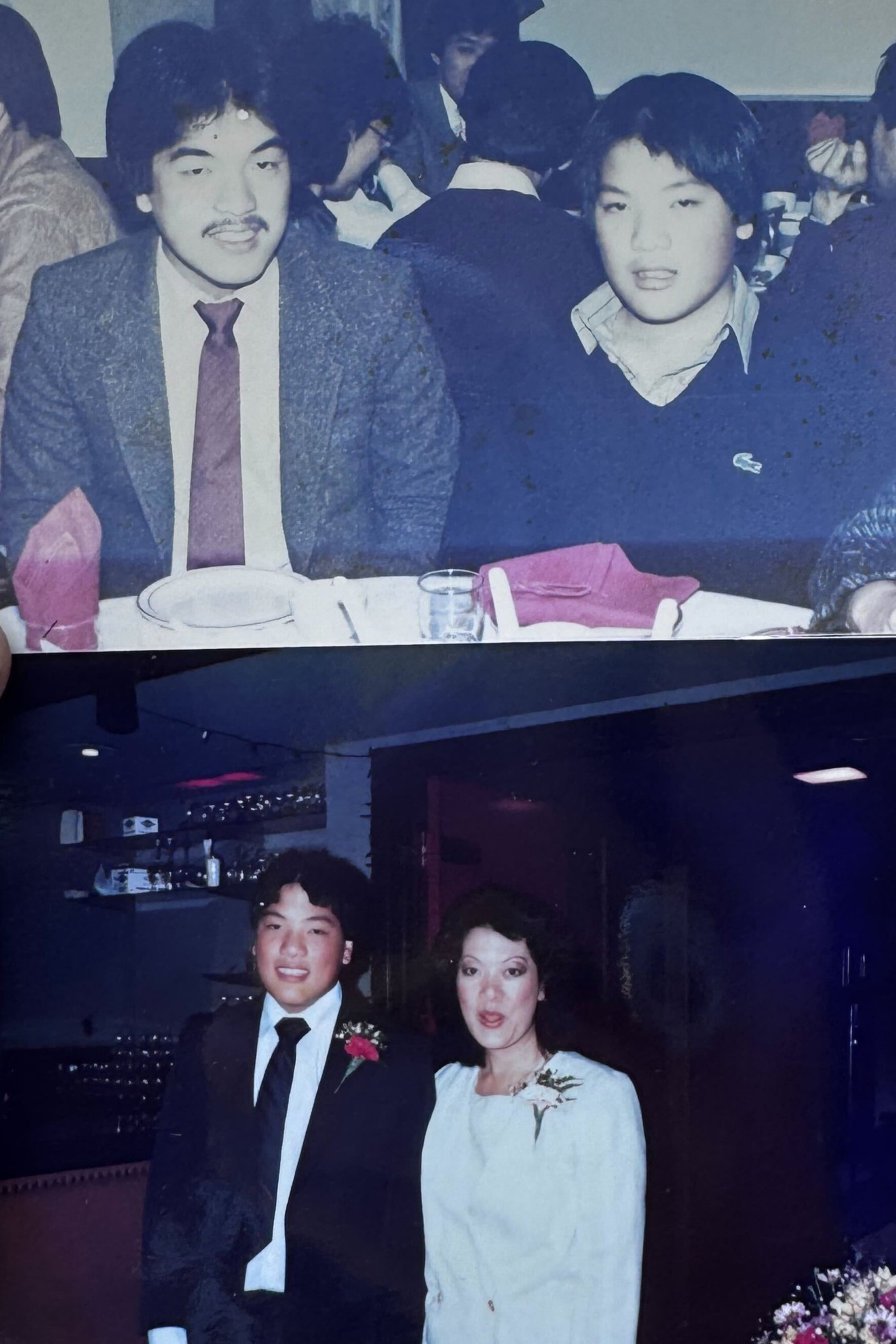

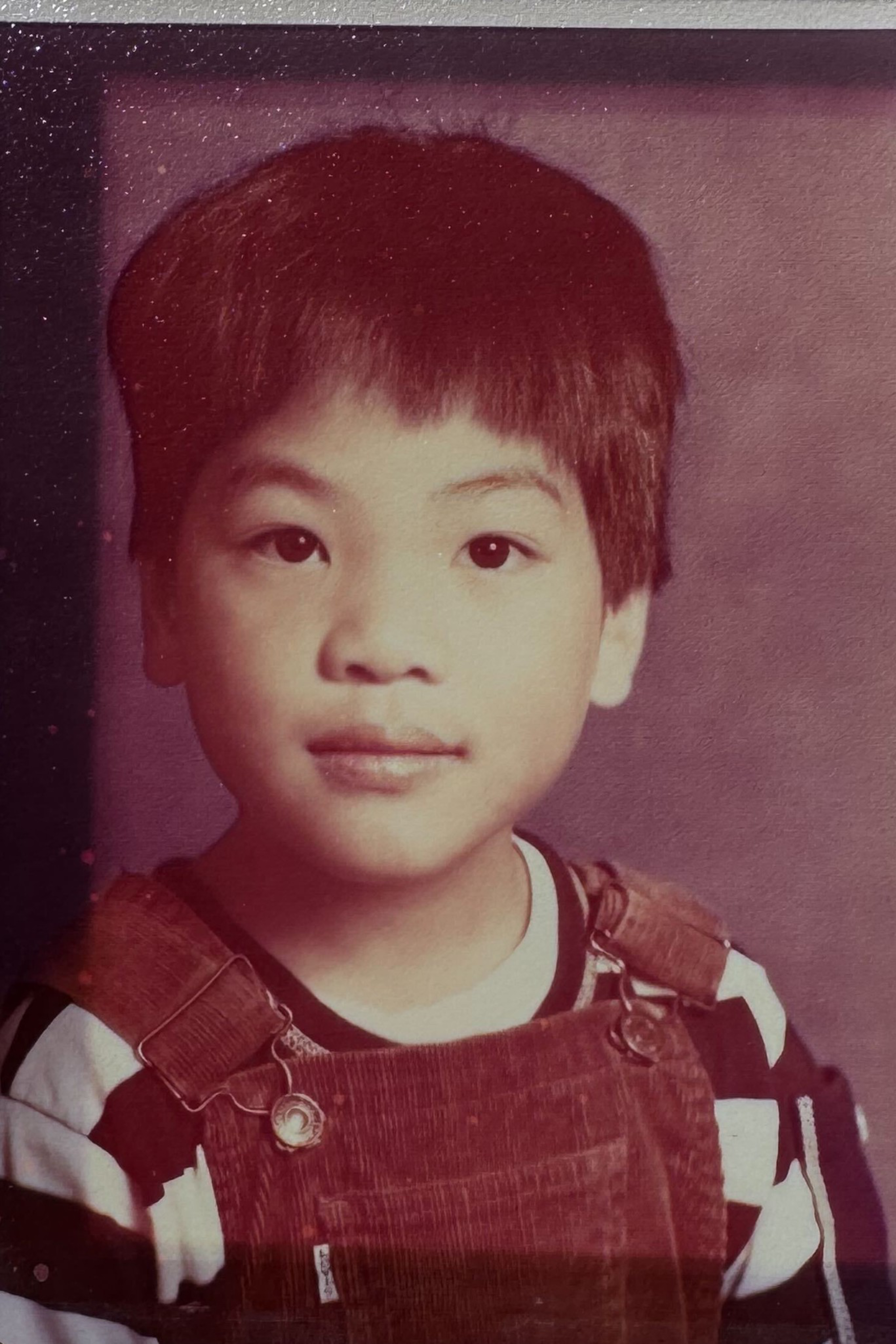

He has previously said he went into law enforcement to help people he witnessed fighting outside his immigrant grandfather Jack Woo’s corner store on the edge of Potrero Hill’s projects.

“I saw a lot of … crime happen, a lot of people fighting for food stamps with razor blades,” Wong said in a department video (opens in new tab). “So, I thought, let’s make a change.”