There’s a common feeling among women’s advocates in San Francisco these days: anxiety.

In a city that once prided itself on leading the fight against gender-based violence, infrastructure built over decades is quickly crumbling.

For over 30 years, the Department on the Status of Women was San Francisco’s quiet powerhouse for domestic abuse reform and support. It’s been the funder that kept shelters, hotlines, and legal aid afloat, the convener that forced reluctant agencies to coordinate, and the policy arm that turned tragedy into reform. Together with the Commission on the Status of Women, it built one of the country’s most comprehensive domestic violence response systems.

Now, that system is at risk of falling apart.

Before she was ousted this year, former department head Kimberly Ellis handed off the department’s $10 million gender-based violence grant portfolio to the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development (MOHCD), an office that primarily focuses on affordable housing.

‘It was a horrible four years. I personally will never be the same.’

Beverly Upton, San Francisco Domestic Violence Consortium

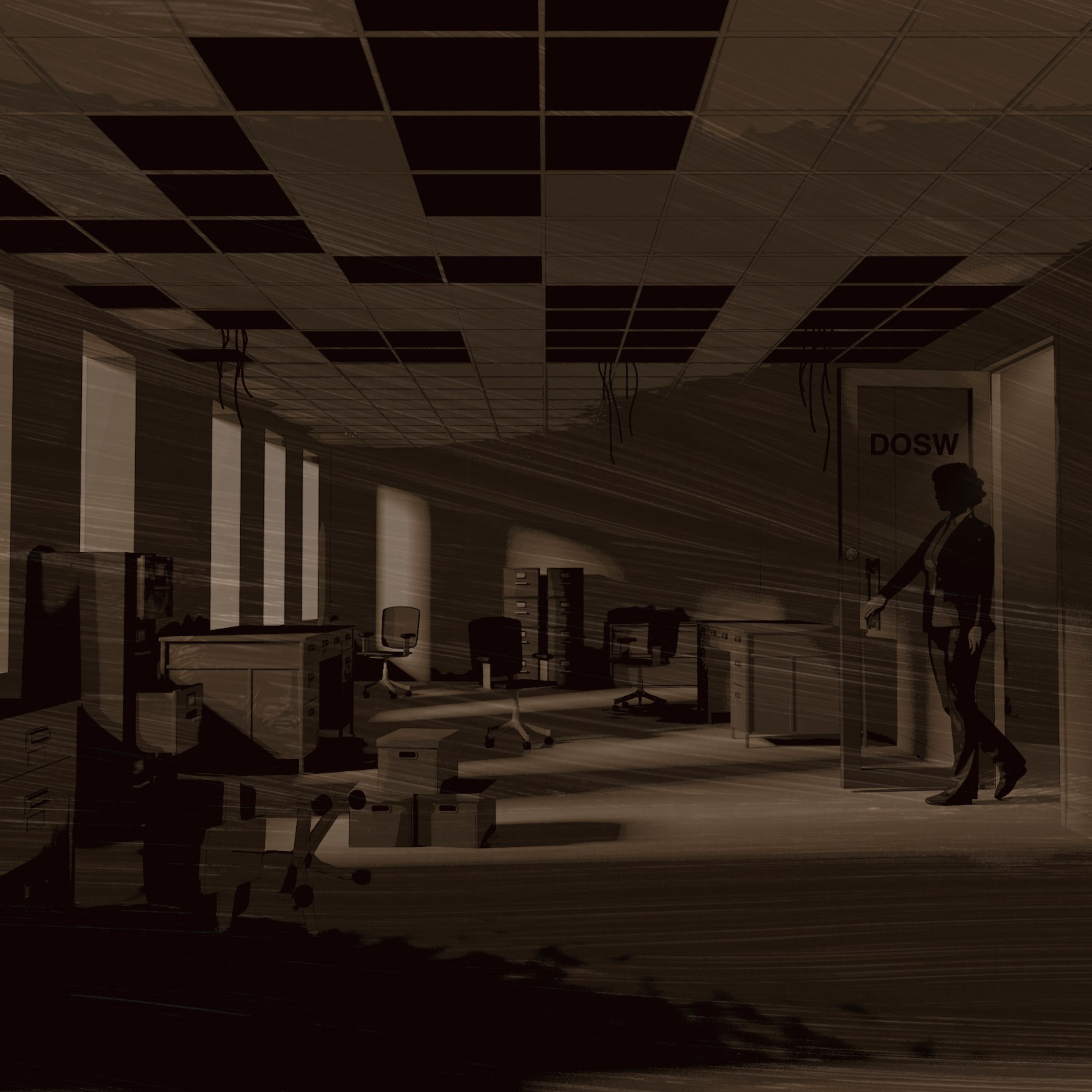

Following revelations that Ellis allegedly mishandled department funds, Mayor Daniel Lurie fired her and folded the Department on the Status of Women into the Human Rights Commission, effectively erasing it as an independent agency.

But the biggest repercussions from Ellis’ tenure are only now being felt by the city’s front-line organizations that work to keep women safe. Some have laid off staff. Others are cutting hours or covering payroll out of dwindling reserves while they wait for delayed city contracts.

The timing couldn’t be worse. Federal officials are rolling back decades of progress for gender equity across the country — chipping away at reproductive rights, civil rights, and workplace equity. The “war on women” is part policy, part rhetoric: In recent months, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth declared women shouldn’t be in combat roles and President Donald Trump said domestic violence shouldn’t really be considered a crime (opens in new tab).

In 2024, the Department on the Status of Women had an annual budget of $16.5 million. Today, it’s shrunk to around $1.4 million.

But advocates say what’s disappeared isn’t just money — it’s decades of hard-won political power and accountability for women, at the exact moment when both are under attack nationally.

‘Every year, we were targeted’

San Francisco’s Commission on the Status of Women was a testament to its era, born from the second-wave feminist movement in 1975. But it was initially met with ridicule. When the proposal for a “women’s commission” first came before the Board of Supervisors, male members huddled together “making private petticoat jokes,” according to a San Francisco Examiner article published at the time.

Then-board President Dianne Feinstein pushed back. “I realize it’s difficult for a man to admit women are equal,” she said.

The commission’s starting budget was just $55,000. But by the 1990s it had affirmed a strong mandate of reform, with the creation of a full-fledged Department on the Status of Women. Together, they built response teams to address violence against women and quickly became a model for other cities.

By 2020, the department’s grants for survivor services had grown to $8.6 million, funding a network of shelters, legal clinics, prevention programs, and crisis lines that collectively served around 20,000 clients each year.

But growing that budget was an uphill battle — a fight that had to be won again and again at city hall.

“Every year, we were targeted for cuts,” said Dorka Keehn, who joined the commission in 1999. “But every year, we fought back.”

That legacy began to unravel with Mayor London Breed’s appointment of Ellis as department director in late 2020.

Ellis — a progressive activist who previously ran a political training program for women candidates — made her intentions clear: She had little interest in domestic violence, despite it being the central focus of the department since its inception.

“Early on she told me she was going to get rid of us,” said Beverly Upton, executive director of the San Francisco Domestic Violence Consortium, the united force of the city’s gender-based violence agencies.

Instead, Ellis had her eyes on politics and events. Her priorities were women’s finances, healthcare, and political empowerment. And getting paid. Under Ellis, the department’s internal costs ballooned. Total staff compensation doubled from about $1 million in 2020 to over $2 million by 2023. Management salaries quadrupled during her tenure, while grantees say they didn’t receive their full funding. During the 2022 and 2023 budget cycles, the Board of Supervisors had added back $1.2 million for the network of nonprofits. But Ellis never fully released the money.

To the shock of longtime advocates, Ellis’ vision wasn’t just talk. She sought to eliminate the department’s gender-based violence grant portfolio entirely.

It’s unusual for any director to want to move funds away from their own department, especially a grant portfolio that made up the bulk of the department’s budget.

“The only reason she gave me is she had bigger plans,” said former Commissioner Caryl Ito, who met with Ellis once she learned of her plans. Ellis did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

“She tried to politicize the department,” Ito said, pointing to Ellis’ penchant for fancy summits with prominent political figures. “Nobody told her you can’t do that. You’re a city department — you cannot play politics.”

Advocates, dependent on this funding for decades, said they were forced to walk a fine line, fearing retaliation if they pushed back.

Ellis’ “alignment plan” (opens in new tab) transferred the department’s grant portfolio — 39 contracts across 27 organizations — to MOHCD, an agency that had previously focused on housing, not survivor services.

In her first memo to the mayor’s office about the plan, Ellis argued that moving the grants would “reframe the narrative around gender-based violence from a ‘woman’s issue’ to a societal issue.”

Most of the gender-based violence organizations were under five-year contracts, set to sunset on June 30, 2025. Suddenly their grants changed entirely.

Under the Women’s Department, competition was limited by design. Staff worked to avoid overlap and make sure the full spectrum of domestic violence services stayed funded. Under MOHCD, however, grantees were told to reapply through a competitive process that accepted over 300 applications across multiple fields. They only learned later that Ellis had given MOHCD inaccurate data about their grants and budgets, baking in reductions before the competitive process began.

Ellis told MOHCD to expect to allocate $8.5 million in grants. According to advocates’ records, the more accurate total would have been closer to $10.5 million. MOHCD also divided the smaller pot further, with grants to new organizations.

“We’re not against new agencies. It’s just hard when there’s no new funding,” said Upton.

For many organizations, the slashed awards were devastating.

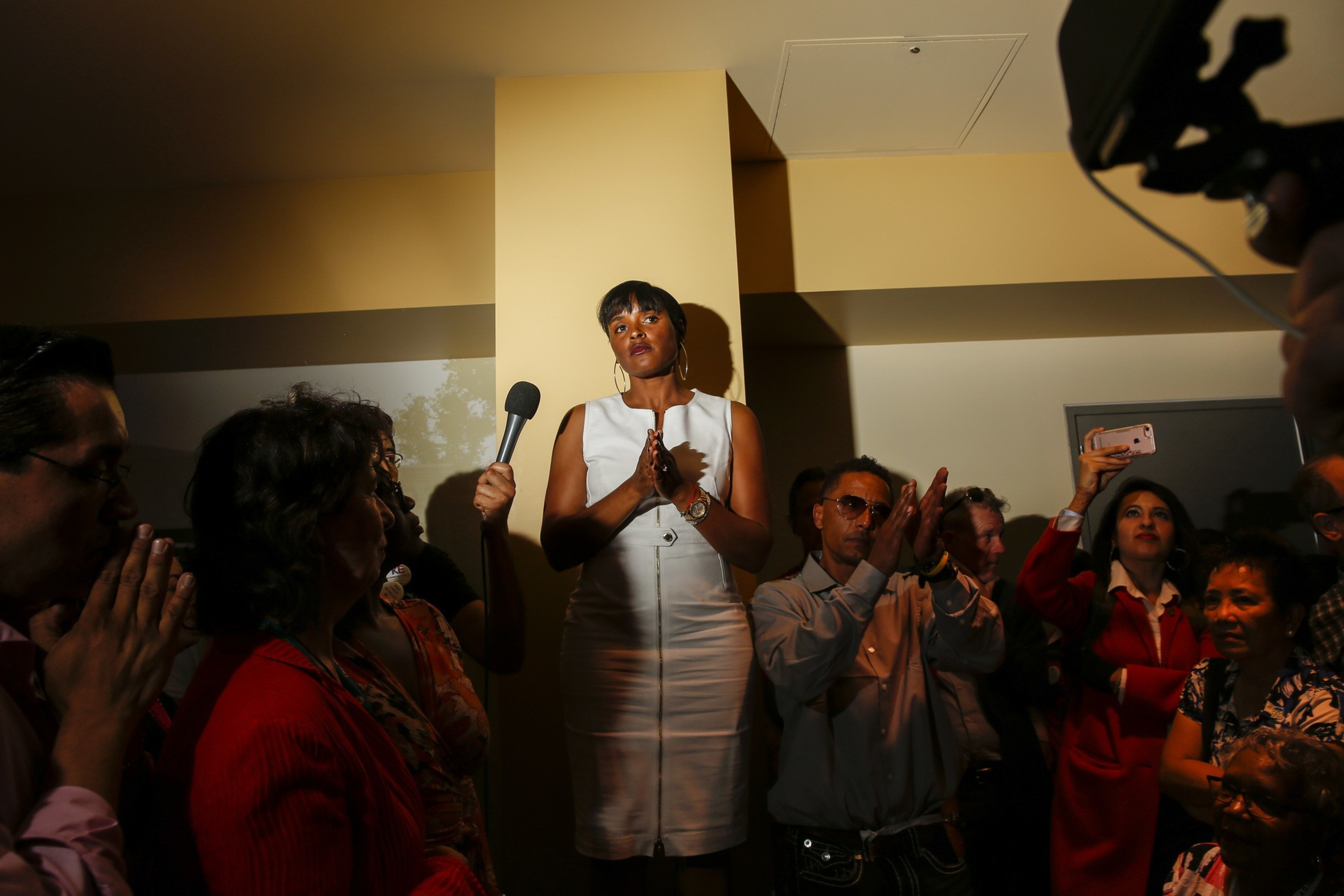

“How am I supposed to pay rent, keep lights on, help survivors, pay my staff?” Pamela Tate, director of Black Women Revolt Against Domestic Violence, asked at a five-hour Women’s Commission meeting in April. Her organization’s funding was cut nearly in half, from $464,000 to $250,000.

At the end of the marathon meeting, commissioners voted to remove Ellis as director. After a series of public revelations about her alleged misconduct and an investigation by the city attorney, Ellis was fired. Dozens of her former employees spoke out about what they described as a culture of fear and intimidation. Her lawsuit against the city over her suspension is still pending.

But the damage to the workers on the ground and the survivors they serve was done.

“It was a horrible four years,” Upton said. “I personally will never be the same.”

Bracing for more pain

With Ellis out and the grants gone, Lurie proposed a plan to merge the Department on the Status of Women with another scandal-plagued oversight body, the Human Rights Commission, whose former director resigned over corruption allegations late last year and is now under criminal investigation.

Women’s advocates begged the mayor to reconsider the merger.

“Isolated failures of leadership must not be used as justification to dismantle the very structure that has supported, protected, and uplifted women for decades,” wrote Lucero Arias, executive director of La Casa de Las Madres in a letter to Lurie. “Women and gender justice deserve dedicated leadership, not broader bureaucracy.”

‘There’s really never been any analogous situation to what we’re experiencing right now.’

Christopher Negri, California Partnership to End Domestic Violence

On July 1, the department was merged into a new Agency on Human Rights. The reorganization gives the human rights director ultimate authority over budget decisions, effectively placing the women’s department under its control.

The city’s grantees feel they’ve lost a focused home that knew how to knit together shelters, legal aid, and police reforms — and defend their budgets.

“This is actually the first year in many years — about 20 years — where we’re getting a cut,” said Janelle White, executive director of San Francisco Women Against Rape, whose organization is receiving $16,000 less than last year.

La Casa de las Madres — the city’s oldest domestic violence shelter and recipient of the department’s first check back in 1980 — is slated to have its grant cut by $76,000, or enough to fund two staffers, according to Arias.

“We are already under staggered schedules to make sure that we have 24-hour coverage,” said Arias.

Black Women Revolt Against Domestic Violence has had to cut back on its crisis line, from 98 hours a week to 20 hours, with no service on weekends.

While the grants technically took effect on July 1, many nonprofits, even those that have signed contracts with MOHCD, have yet to access the funds.

According to Anne Stanley, communications manager at MOHCD, the entire $8.5 million gender-based violence portfolio — plus an additional $902,000 increase — is being distributed, but not all contracts are finalized. Until then, the agency declined to share allocated amounts. The estimated completion is in the next week or two.

The application process “was highly competitive,” Stanley said. “Unfortunately, this meant that not all eligible proposals could be funded, and some long-standing programs were further impacted by fiscal conditions in 2025.”

Advocates are hopeful that the MOHCD, which hired staffers with experience handling survivor grants, will be able to pick up the pieces.

“We’re feeling optimistic about working with the new administration,” said Upton, who added that women’s advocates have been meeting with Lurie semi-regularly since he took office.

‘There’s really never been any analogous situation to what we’re experiencing right now.’

Christopher Negri, associate director of policy, California Partnership to End Domestic Violence

Still, the biggest toll for now, advocates say, is the stress and uncertainty about whether their programs can continue.

“There’s really never been any analogous situation to what we’re experiencing right now,” said Christopher Negri, associate director of policy at the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence.

In San Francisco and across the state, the local funding crisis is compounded by federal cuts. (opens in new tab) Most domestic or sexual violence organizations rely heavily on federal grants.

New legal requirements for federal funds have left nonprofits scrambling. Organizations are no longer allowed to mention diversity, equity, inclusion, or gender identity in their grant applications, making it nearly impossible for many of the affected organizations in San Francisco, which have those key words in their names, to receive any funding.

Between the combined loss of city and federal dollars, Tania Estrada, executive director of the San Francisco Women’s Building, has been forced to lay off eight employees.

“These decisions are going to cause ripple effects in our communities,” she said. “Losing even temporary funding has lasting consequences.”

The future of the Commission on the Status of Women also remains uncertain. The Prop E-mandated Commission Streamlining Task Force (opens in new tab) began meeting in January, holding hearings and collecting public feedback on which of the city’s more than 130 commissions should stay and which should go.

The task force’s latest memo (opens in new tab) noted the commission’s legacy and its narrowed power after losing its grant portfolio, leaving it with primarily policy oversight, research duties, and a public engagement platform. The task force found no reason to eliminate the commission ahead of its review on Oct. 15, but suggested the commission could shift to an “advisory role,” further limiting its power.

More than 30 letters of support have poured in to try to save the commission from what many fear will be its demise in the name of efficiency.

“Disbanding the COSW would not only signal a lack of priority for women’s issues, but also reinforce the dangerous notion that women’s voices and rights are dispensable,” wrote Rebecca Jackson, co-chair of the SF Women’s Housing Coalition. “This is something we cannot accept.”