“Stop using drugs,” read the usual note that overdose victims were handed as they left the hospital during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s.

Arms covered in track marks. Dragged in against their will. Spoiling for a fight with staff. Almost always on death’s door. The hospital was the only place that Diane Jones, a former nurse at San Francisco General, remembers interacting with drug users. Day after day, it admitted and discharged these patients without a treatment plan, she said.

Then, in the early ’90s, Jones and a handful of her colleagues learned about a new medical framework: harm reduction.

Drawing on methods that had shown promising results with heroin users in the South Bronx, the nurses learned to build relationships with their drug-addicted patients. They collaborated with social workers to open programs such as needle exchanges outside the hospital.

The science would lead to success: Needle sharing dropped from 66% in 1987 to 36% in 1992, according to the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. The number of HIV cases among people injecting drugs dropped by half from 1992 to 1998 and has continued to slow in the years since.

“We were doing a terrible job treating these patients,” Jones said. “But little by little, things improved when harm reduction became the official policy of the health department.”

Forty years later, that same policy is now in the crosshairs of the city’s leaders.

As fentanyl ripped through the nation’s drug supply, killing more than 3,500 San Franciscans since January 2020, chaotic scenes of public drug use cast a harsh spotlight on the city’s handling of the epidemic and the theory underlying it. Recovering users came forward to criticize harm reduction’s dogma, alleging it facilitates deadly drug use by supplying users with smoking supplies, such as foil and pipes, and fails to guide them to treatment.

In essence, they argue that San Francisco took the concept too far. Increasingly, the people in charge of the city’s $3 billion public health machine agree.

“What harm reduction really started for is not what’s happening now,” said Cregg Johnson, a director at the TRP Academy, an abstinence-based rehab. “We’re running around here enabling people to use drugs.”

In late February, Supervisor Matt Dorsey introduced a new policy, the “Recovery First Ordinance (opens in new tab).” If passed, the policy would direct the city to fund more abstinence-based treatment, which is often portrayed politically as the opposite of harm reduction policies.

Earlier this month, Mayor Daniel Lurie introduced an expansive set of goals for tackling homelessness and drug use called “Breaking the Cycle,” which, among other things, calls on the city to “reassess” distributing fentanyl-smoking supplies, a strategy that aims to steer users away from injecting drugs.

Public health director Daniel Tsai told reporters last week that a plan for “pivoting” from providing supplies is in the works.

“We need to know that everything we’re doing is making a dent,” Tsai said.

While the message was delivered in bureaucratic language, the takeaway of the past few years is clear: In San Francisco’s war of public opinion, harm reduction is losing — badly.

The city’s harm reduction disciples, many of whom are also recovering from addiction, are dismayed to see their coalition so quickly discredited — and even blamed — for the crisis after decades of service.

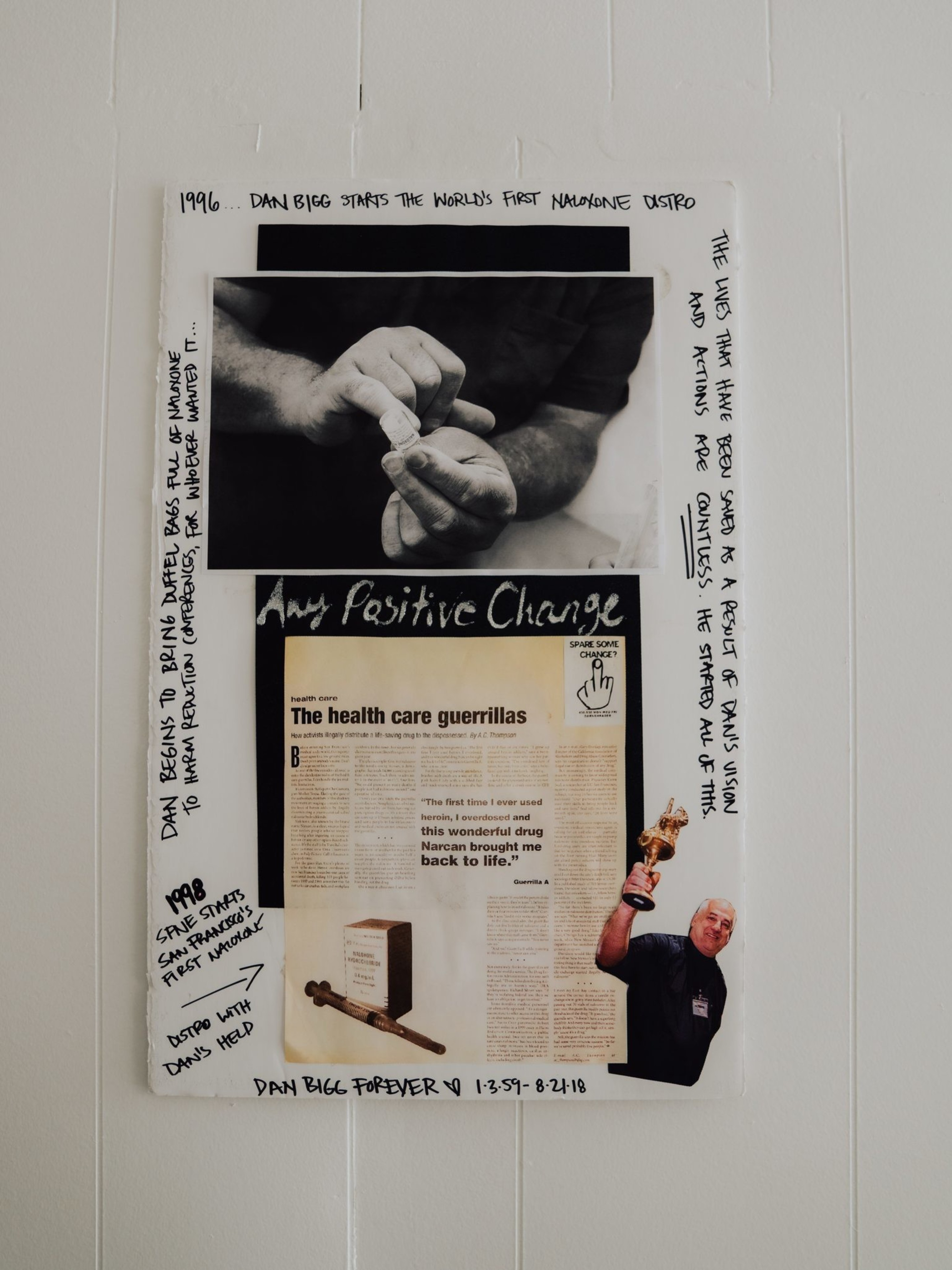

They argue that without their advocacy — which led to the stockpiling of Narcan, an overdose antidote, as well as the creation of the city’s Treatment on Demand policy — San Francisco would have been caught completely flat-footed by the emergence of fentanyl. By chipping away at harm reduction approaches, they argue, the city is limiting the tools at its disposal to fight the crisis.

“Even in the worst of the overdose epidemic, it was our community that was called. We worked hours and hours. We worked with people in public housing, we worked with people on the streets, we worked in shelters,” said Laura Guzman, executive director of the National Harm Reduction Coalition. “Now, we feel like we’re going back 35 years.”

‘Do it with friends’

If there was a single moment when the discourse around harm reduction turned toxic, it may have been the Department of Health’s 2020 release of an ad campaign aimed at drug users. Meant to reduce overdose deaths, which typically occur in isolation, it struck many as a lifestyle endorsement.

“Do it with friends,” read one billboard in SoMa, which featured a picture of people partying. “Use with people and take turns. Try not to use alone, or have someone check on you.”

From a medical standpoint, the message was simple: Drug users can’t be treated for addiction if they’re dead. But political condemnation (opens in new tab) was swift.

It was not a good time to circulate ads of smiling drug users, critics said. Roughly two San Franciscans were dying of overdoses every day. Bustling drug markets made some street corners virtually impassable. The city was on the brink of collapse, according to international headlines and social media pundits.

“Unlike the needle exchange in the ’90s and 2000s where you can point to HIV numbers going down, overdoses were spiking,” said Jeff Cretan, a top communications staffer for ex-mayor London Breed. “People seeing that, they get frustrated and they want answers. And then they also want to blame something, which is understandable.”

In October 2021, author and gubernatorial candidate Michael Shellenberger published a book titled “Sanfransicko,” which blamed progressive policies for the city’s street crises. He recorded interviews with drug users, who admitted to gaming the city’s social safety net to feed their addictions.

“I get paid to be homeless in San Francisco. It takes one phone call,” one homeless man told (opens in new tab)Shellenberger. “Why would I want to pay rent? I’m not doing shit. I’ve got a fucking cell phone that I have Amazon Prime and Netflix on.”

In the following years, the city was besieged by video after video posted online of public drug use. Influencers such as Ricci Wynne, who was recently charged with producing images of child sexual abuse and pimping offenses, built massive followings by producing viral videos of the most gut-wrenching drug-addled misery.

In late 2021, Tenderloin families pushed Breed to act. Stories of schoolchildren being accosted by drug users stirred her, prompting a speech declaring she had enough of the “bullshit.” It seemed she was primed to take a stricter stance.

Instead, the city opened the Tenderloin Linkage Center, a safe drug use site, in United Nations Plaza. In just under 11 months, staff at the site reversed 333 overdoses, provided more than 99,000 meals, 8,900 showers, 3,400 loads of laundry, and 1,500 completed referrals to housing and shelter. Drug users called the facility a lifesaver.

But fatal overdoses increased slightly in the year the site was open. Conditions around U.N. Plaza worsened, locals said. The number of people admitted to drug treatment continued to decrease.

A few months after the site opened, city officials dropped the word “linkage” from its name after it failed to connect many drug users to rehab.

Advocates and drug users warned that more tragedy awaited if the center closed. But city officials found the $22 million price tag too large to justify. Plans to build a network of smaller drug sites across the city lost support amid legal uncertainty.

‘The battle is over’

After the Tenderloin Center closed, Mayor Breed again went on the offensive against open-air drug use and its perceived enablers. But this time, she matched her words with action.

“Compassion is killing people,” she proclaimed at a May 2023 meeting in U.N. Plaza. “We have to put forth some tough love to change what’s happening on the streets of San Francisco.”

In the following months, local, state, and federal law enforcement descended on the Tenderloin, chasing dealers and users through the streets and filling up local jails. Harm reductionists condemned the changing tack. But their message had lost political influence. Breed pushed forward, introducing a slew of antidrug policies.

That year saw 810 people die of overdoses, the most in the city’s history. Some drug policy experts blamed the increased enforcement. They said many users were overdosing in isolation, and the drug supply was less predictable and, therefore, more deadly.

But some residents celebrated improvements in previous drug hotspots such as U.N. Plaza. And by January 2024, more than 1,900 arrests later, the tide seemed to have turned again.

In 2024, the potency of fentanyl plummeted, according to drug users and service providers. The city saw a decrease in overdose deaths, following a national trend, reaching the lowest level locally since before the pandemic. The number of treatment admissions coincidingly increased for the first time since 2015.

It’s unclear what caused the reversal in fortune. But Breed claimed the city’s change in strategy was proving successful. Most candidates in last year’s mayoral race agreed.

“We need to focus on shutting down open-air drug markets,” Lurie said early in his campaign. “San Francisco should not be a shining beacon for drug tourism.”

In a statement, Lurie’s spokesperson said he is focused “on results, not labels that mean different things to different people.” But three months into his administration, many service providers say it’s apparent he has picked a side. The changing policy could cause the reallocation of millions in city funding come budget season.

Vitka Eisen, CEO of the harm reduction nonprofit HealthRIGHT360, told The Standard earlier this month that City Hall had effectively ghosted her nonprofit.

“Nobody talks to us,” said Eisen, whose organization holds more than $295 million in contracts extending until 2030.

Several service providers who were previously outspoken in their criticism of harm reduction are now less enthusiastic to speak publicly on the matter.

“The battle is over. I don’t want to spit on their grave,” said the director of an abstinence-based nonprofit, who only agreed to speak anonymously.

Josh Bamberger, the doctor who is widely credited for crafting the health department’s harm reduction policy two decades ago, said the unwillingness to collaborate will lead to more deaths.

“Harm reduction has become a political cudgel, rather than having a scientific meaning,” Bamberger said. “Everything we do in medicine is harm reduction.”

In the absence of thoughtful discourse, one metric reigns supreme: the number of lives lost.

When overdoses drop, members of both sides rush to take credit.

During months with more deaths, finger-pointing ensues.

In February, the death toll was 61, up from 57 in January.