For more than two decades, the international law firm Morgan Lewis called One Market Plaza its home in San Francisco. The property, which features two office towers flanked by a historical annex, sits at the terminus of Market Street, with unobstructed views of the Embarcadero waterfront and Bay Bridge. But despite the top-tier location, Morgan Lewis began searching for a new home in 2023, with less than three years left on its lease.

The firm took its first tour of the Transamerica Pyramid last April, sources say, and found itself returning to the property repeatedly over other listings. Even though New York developer Michael Shvo’s building was still a construction site, Morgan Lewis got an offer it couldn’t refuse: seven floors, totaling 123,000 square feet, and a promise from the landlord to spend upwards of $350 per square foot on renovations and other concessions.

Other landlords, even in some of the city’s most prestigious corridors, were offering $175 to $250 per square foot in tenant improvement allowances, according to brokers.

Morgan Lewis signed a 20-year lease at the Transamerica Pyramid last month. A spokesperson said the firm intends to move in the first quarter of 2026. When it does, it will vacate its seven floors, totaling 149,000 square feet, at One Market Plaza.

One trophy building wins at the expense of another — that’s often how it goes in the zero-sum game of San Francisco real estate. But since the pandemic, with fewer tenants circling a number of increasingly desperate properties, the contrast is starker than ever. Landlords who saw office tenants embrace remote work are left with a string of vacancies that have tarnished their buildings’ reputation among companies and lenders, who see them as “expired (opens in new tab)” assets, as Shvo has put it.

Meanwhile, those owners who were able to revamp or upgrade their buildings during the fallow period are securing prime leases, as more companies seek a rebooted physical space to push for in-person work.

“Our view is that it’s not just an office,” said Brent Hawkins, managing partner of Morgan Lewis’ San Francisco office. “The [Transamerica Pyramid] puts us at the heart of one of San Francisco’s most dynamic neighborhoods.”

He added that the office renovations will be heavily focused on “collaboration, ergonomics, light penetration, flexibility, and health and wellness.”

On paper, One Market Plaza possesses the attributes to deliver all of those. Combining an indoor park, retail, restaurants, and a food court, it has the components of an “urban campus” of the type that office developers and tenants crave. But those components are mostly sitting empty.

Five of the six retail spaces in the ground-floor atrium are vacant. In addition to Morgan Lewis, other signature office tenants are departing the property next year, including Google, which will vacate more than 340,000 square feet, and Visa, which will leave its 161,822 square feet for its new Mission Rock headquarters.

When Paramount Group partnered with investment firm Blackstone to purchase One Market Plaza in 2007, it was the envy of the city’s office market and commanded top rents. Paramount paid $720 million for a 50% stake.

Leasing momentum at the building was once so strong that the ownership group executed a $975 million loan for the property in 2014. But the bill came due at the worst possible time.

Last year, the landlord charged approximately $112 per square feet, according to Paramount’s 10-K report. At that price, brokers put it in the same category as Salesforce Tower, 555 California, and One Maritime Plaza. But One Market Plaza no longer measured up to those competitors. And with a maturity date of February 2024 for its nearly $1 billion loan, Paramount Group and Blackstone were staring at a bill that no longer matched the property’s sinking value — which fell to $1.25 billion last year from $1.76 billion in 2016.

According to loan reports, the borrowers approached numerous lenders at the start of 2023 to refinance but failed to strike deals; a year later, the loan landed in special servicing, a precursor to foreclosure.

“Vacancy combined with a maturing loan is a ticking time bomb,” said a Class A office broker who requested anonymity to protect working relationships. “That’s when the lender starts to get involved in every aspect of negotiations and can override promises made by the borrower.”

“It’s not a total dealbreaker, but it’s friction that tenants would rather avoid if they can help it,” the broker said. “They’re not going to want to sign anything with a landlord who won’t be around.”

Shvo buys time

The revival of the Transamerica Pyramid is a feel-good story in a city desperate for a turnaround, but Shvo and his investors are far from out of the woods. They just have more time on their hands.

For starters, fully leasing the iconic skyscraper, even at the highest rental prices in the city, would fall short of covering the $1 billion Shvo’s group is spending to renovate the 48-story structure and build out the area surrounding it.

Experts say the only way the group can make any returns on the project is to expand the rentable commercial space adjacent to the pyramid and to increase its public use through new retail and events. Shvo’s purchase of the property in October 2020 included two office buildings at 505 Sansome St. and 545 Sansome St.

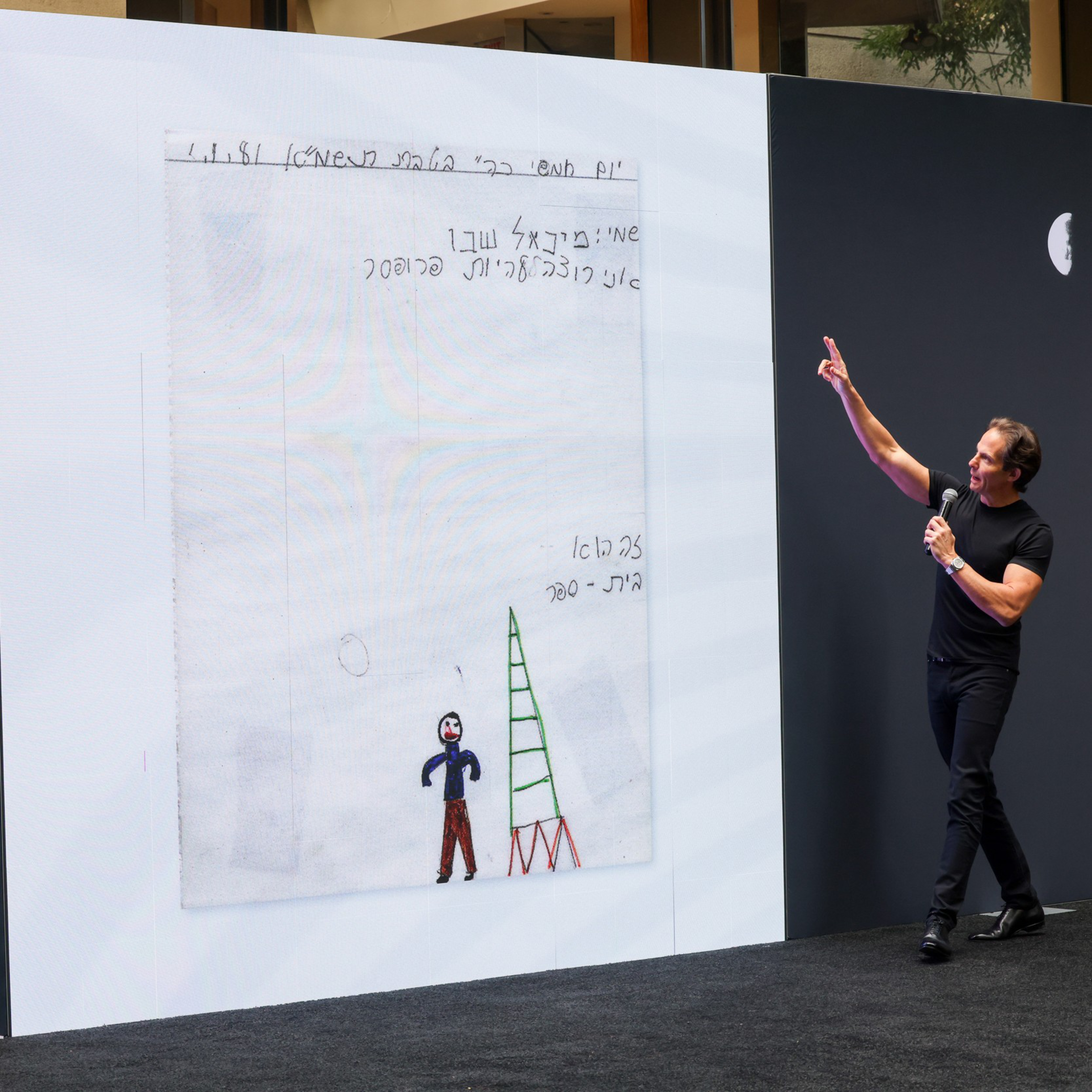

The momentum is headed in the right direction, even if it took the city’s highest tenant concessions to woo Morgan Lewis. The San Francisco Chronicle reported this year that crypto investment firm Paradigm, which has raised $850 million in capital, is eyeing a 40,000-square-foot lease (opens in new tab) in the building. A source familiar with Paradigm said other crypto investment firms — Pantera, Blockchain Capital, and Framework — have been flocking to the bar on the 48th floor of the pyramid for networking and meetings.

Rents start at about $115 per square foot for levels near the pyramid’s base and reach about $300 per square foot at the top.

Shvo, who leads his eponymous development firm, has attracted controversy at the property. Two months before the pyramid’s public reopening in September, CORE: Holdings, the operator of a planned ultra-luxe private club at the building, sued Shvo and his investors for $600 million, alleging fraud. The lawsuit seeks to terminate the would-be tenant’s 20-year lease agreement.

Shvo has countersued, and while the legal saga continues, the two floors leased by CORE were put on the market last month. The San Francisco Business Times reported that Shvo’s group stands to lose almost $180 million in rent (opens in new tab) if the courts allow CORE to rescind its lease.

Paramount pulls back

Meanwhile, New York-based Paramount Group, which owns nearly 4.3 million square feet of San Francisco office space, including One Market Plaza, has gone from growth mode to firefighting mode.

Peter Brindley, head of real estate at Paramount, told investors on an earnings call last month that 66% of the company’s expiring San Francisco leases were from Google and JPMorgan; the latter acquired First Republic Bank, a major tenant at another Paramount property, One Front St.

Paramount is also under scrutiny for reporting previously undisclosed payments (opens in new tab) of at least $4 million to President and CEO Albert Behler for personal expenses and business interests, including jet-chartering services and fees paid to a design firm owned by his wife.

While Paramount has effectively written off two of its six San Francisco office assets, it is attempting to retrench at One Market Plaza. Last February, it agreed to pay $125 million to lenders in exchange for an extension that could see its loan maturity pushed back to 2028, if certain conditions are met.

“Our strategic decision to invest in the property and move forward with a plan to further enhance its amenities demonstrates our confidence in its long-term potential as a preferred office destination,” said a company spokesperson.

Paramount’s commitment to One Market has reassured new tenants, including Alison Neri, a former lawyer who opened her gift shop, Ruby’s Old & New, in the atrium in March after cold-calling the listing broker a month earlier.

Ruby was the name of Neri’s great-grandmother, who once worked as a switchboard operator in downtown San Francisco, so the lease represented a full-circle moment for the family. The shop, which offers an array of goods made mostly by women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ artists, cuts a colorful contrast to the row of otherwise empty spaces in the ground-floor corridor.

“Everyone from the leasing team to the building staff have been so willing to help with anything, big or small,” Neri said. “It might not look like it, but there is a little community forming here.”