Sasha Perigo dropped a political atom bomb on San Francisco in the summer of 2021 when she accused Jon Jacobo of raping her months earlier at his apartment.

Jacobo was a director for TODCO, one of the most politically powerful housing nonprofits in the city, and a rising star in the local Democratic Party’s progressive wing. If things had gone according to plan, Jacobo would be campaigning right now to become a San Francisco supervisor.

But in a social media post, Perigo, who also works on affordable housing, linked to a seven-page document laying out details of the incident, including what she said were test results from her rape kit and screenshots of text messages she sent Jacobo. One read: “you literally looked me in the eye and took my pants off AS I WAS TELLING YOU NO.”

Jacobo denied the accusations and said the encounter was consensual. The allegations would fracture San Francisco’s political community. Elected officials and community organizers were forced into an uncomfortable position: remain loyal to an ascending political figure or prove their professed support for the #MeToo movement was more than lip service. Most officials ended up awkwardly straddling the fence by saying they supported women as well as due process.

Perigo declined to press charges against Jacobo, citing her distrust in the criminal justice system, but she wanted him to be held accountable. She said she decided to go public after learning he “not only pushed boundaries with other women in the past, but was continuing to do so.”

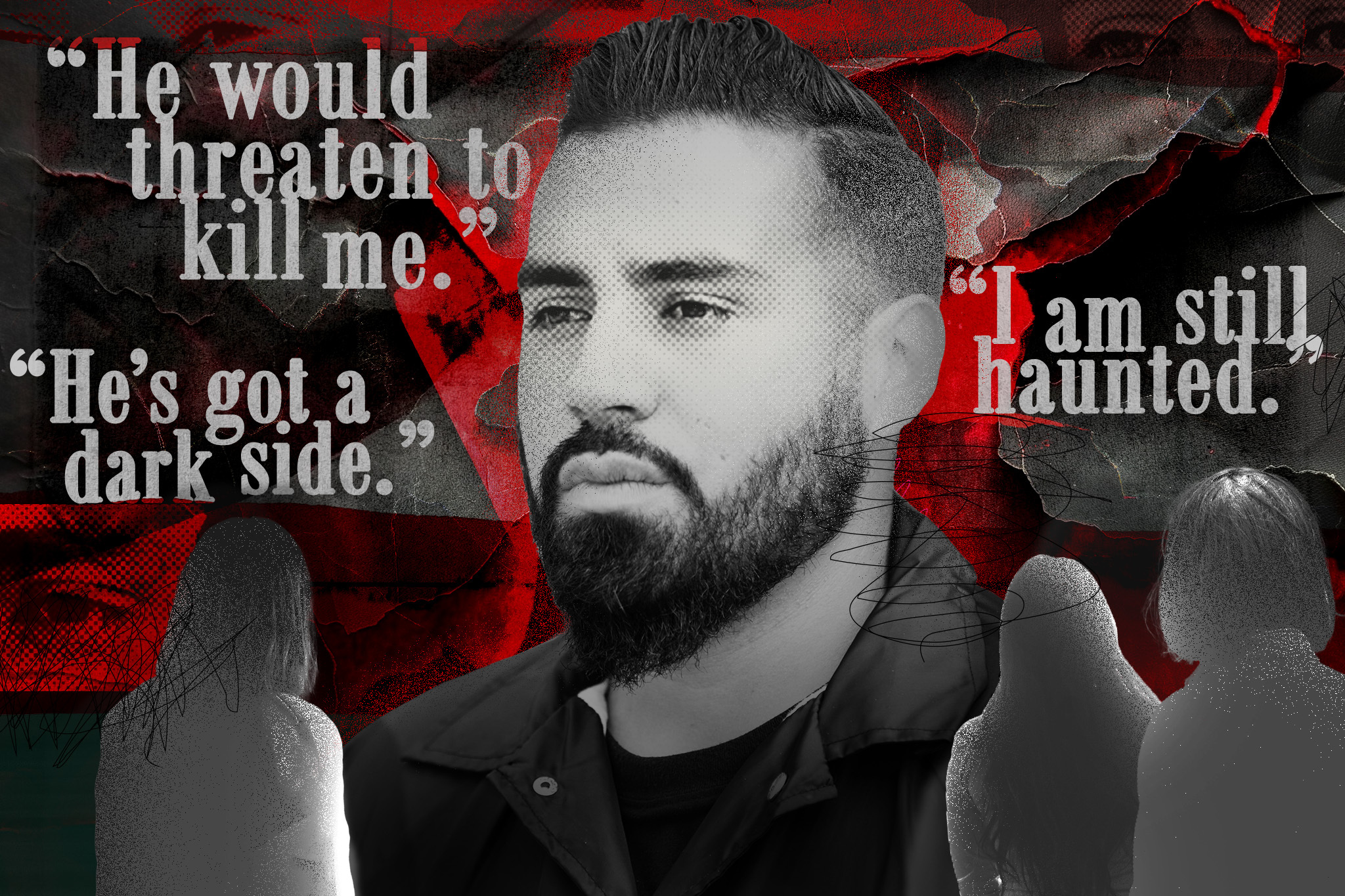

The Standard has since learned that three women filed police reports against Jacobo in the months following Perigo’s public rape accusation. In a series of interviews, the women detailed disturbing allegations against Jacobo that range from stalking, harassment and threats to domestic violence, strangulation, sexual assault and rape, which formed the basis for their police reports.

“As time went on, he would threaten to kill me constantly,” said a woman who was in a relationship with Jacobo for years. “It started off as jokes and later escalated to direct, repeated threats. And that was terrifying.”

The women shared audio recordings, text messages, photos and other evidence with The Standard to support their allegations, some of which they also shared with the SFPD. It’s unclear how thoroughly law enforcement attempted to investigate the women’s allegations against Jacobo, and the cases, while open, appear to be languishing. Jacobo did not respond to multiple calls, a text and an email with questions from the Standard.

One of the women who filed a police report said her phone calls to police went unreturned, while the two others said they felt discouraged by their interactions with officers. Friends and colleagues of the women who learned of the incidents contemporaneously told The Standard that they have never been contacted by police.

Evan Sernoffsky, a police spokesperson, said the department takes sexual assault cases seriously and works “tirelessly” to stay in constant communication with victims through the entire process of an investigation.

“We urge anyone who is a victim of sexual assault to come forward and report your case to the SFPD,” Sernoffsky said.

All three of the women have worked at high levels of local government and public policy in San Francisco, and spoke to The Standard on the condition they not be named publicly for fear of jeopardizing their political careers and perhaps their safety. They felt brushed aside in attempting to inform TODCO officials and former Supervisor Jane Kim—who hired Jacobo during her time at City Hall after he worked on her 2018 campaign for mayor—of their experiences with Jacobo.

John Manly, a longtime attorney for victims of sexual assault who was lead counsel on the sexual abuse case against ex-USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar, told The Standard that it’s especially important for police to thoroughly investigate cases with allegations coming from multiple women.

“To allow somebody in a position of authority and trust to go uninvestigated—as it appears to me here—is profoundly dangerous and unfair to the alleged victims,” Manly said. “Such an investigation may show a basis to charge him criminally or exonerate [Jacobo], but either way it’s important.”

He added, “San Francisco law enforcement and political leaders can’t claim to be progressive on all issues, like women’s rights, and then drop the ball here.”

The prince of progressive politics

The first woman to go to police with allegations against Jacobo dated him for approximately three-and-a-half years, starting in 2015, when both were active in San Francisco’s political scene. The woman said her first impression of Jacobo was one of a charming and driven activist, but over time, she saw a darker side.

“Jon described himself as a very calculating person,” she said. “He would talk about how he sought out friends or work associates, viewing his relationships like a chessboard. He would brag about using people to gain positions or leverage someone to get in another political circle.”

Jacobo began physically abusing her during the first year of their relationship, she said. The woman said Jacobo choked her multiple times, frequently trapped her in their South San Francisco home, pointed a gun and knives at her, and repeatedly threatened to kill her and family members.

In drunken fits of rage, she said, Jacobo destroyed furniture, her laptop and a watch, and broke the hinges off a door in their home. He also stalked and harassed her at work, she said.

“The more I understood the way that Jon’s mind works, the more disturbing it was,” she said.

The woman shared text messages with The Standard that show his temper and indicate Jacobo pressured her into lending him money; she said he often never paid her back.

Her memories of a vacation they took to Costa Rica in 2016 included locking herself in an Airbnb bathroom as Jacobo accessed her personal computer, took her passport and threatened to leave her stranded abroad without her belongings. In voice recordings obtained by the Standard, Jacobo can be heard bragging about being able to track her movements—even when her phone was turned off.

The woman told police that during a 2017 hotel stay in Santa Cruz, Jacobo strangled her on the bed after the two attended her work event.

The woman considered seeking help from community leaders in the Mission, where she worked, but believed none would aid her because of Jacobo’s many ties to local organizations. In addition to working at City Hall, he was the co-founder of the Latino Task Force, co-president of the Latin@ Young Democrats of San Francisco and vice president of the nonprofit Calle 24.

Adding to her fears, she said, Jacobo frequently talked about being acquainted with Norteño gang members. An ABC7 report in 2019 documented Jacobo hanging out with Fernando Madrigal, who claimed to be a reformed gang member. Madrigal later pleaded guilty to killing a 15-year-old boy in 2019.

Jacobo’s connections acted as a “silencing factor,” she said.

Finally, in 2019, the woman started a new job at Oakland City Hall and managed to move out of the home she shared with Jacobo. Her fear of Jacobo drove her to live in hotels for months. She kept a suitcase packed with clothes in her trunk, stopped posting on social media accounts, bought a burner phone and avoided interacting with their friend groups, she said.

“It got so bad,” she said, “that I literally thought about moving to another country just to escape him.”

‘What you do when it’s survival’

In December 2018, Cynthia Wang—a San Francisco entertainment commissioner and former assistant city attorney in the Bay Area—received a phone call from a close friend who had worked for years in San Francisco public policy and at City Hall. Wang could immediately tell her friend was upset.

“Something happened to me last night with Jon,” the woman told her. “He was really pushing aggressively … and I was scared.”

The woman had invited Jacobo over to her apartment after flirting for weeks by text. She suspected he was in a long-term relationship—he was, in fact, still living with the first woman to come forward in this story—but she didn’t know for sure. He was a smooth talker, she said, to the point that she couldn’t tell if he was genuine. Jacobo had told her on a previous date that he and his girlfriend had separated, but she was still living in their South San Francisco home.

The night Jacobo came to her apartment, the woman knew he had been drinking, but they had agreed to just hang out and talk.

“From there, it just completely escalated,” she told The Standard.

Shortly after arriving, she said, Jacobo threw her onto her bed and got on top of her. She said she struggled as he tried to remove her pants, telling him “no” multiple times, but then a moment of fear gripped her.

“I had heard stuff in the past—even from some of his own friends—that he can become very violent,” the woman recalled.

She continued to resist Jacobo until realizing he wasn’t going to stop, she said. She finally gave up and told him to at least put on a condom.

“When you’re in a state of shock, you just have to think about what’s the best way to protect yourself,” the woman said. “I had to do what you do when it’s survival.”

Months went by, and she repeatedly broke down in tears during her and Wang’s conversations about the incident. The woman said she started going to therapy and only later realized that what she had experienced was rape.

Then, in 2021, she learned of Perigo’s accusation against Jacobo. The details of Perigo’s account brought back all the trauma of her own experience.

“The way she described it, I just felt completely numb,” the woman said.

The woman said she spoke with close associates of Jane Kim—the former supervisor who had hired Jacobo as a staffer and now runs the California chapter of the Working Families Party— and shared details of her encounter with Jacobo.

People the woman contacted included April Veneracion Ang, a legislative aide who now serves on TODCO’s board, and Bobbi López, Kim’s legislative director who went on to work with TODCO before joining San Francisco’s Department of Public Health to work on victim services. The woman said that Ang and López assured her that they would tell Kim there were other victims. Neither Ang nor López responded to requests for comment.

In late October 2021, the woman filed a report with San Francisco police.

“When sharing the story with police, I wasn’t even sure if the officers were going to believe me,” she said.

In 2022, the woman decided to leave San Francisco. She found a job outside the area that would help her avoid Jacobo and the city’s “toxic” political scene.

“I had to make a decision to leave the community that I worked so hard for, because people weren’t backing me up,” she said. “It wasn’t for a lack of trying.”

Shortly after Perigo’s rape allegations in 2021, Kim brought Jacobo to a Rose Pak Community Fund fundraising gala. The SF Women’s Political Committee, which issued two statements in support of Perigo, said it was “shameful and unacceptable” for people to be ushering Jacobo back into the political world.

Meanwhile, Kim was also trying to help Jacobo find an attorney, according to a source who told The Standard that Kim asked them for help.

In a phone interview, Kim expressed surprise that three women were coming forward with allegations. She told The Standard she was unsure of the details of her conversations because they happened years ago, but she denied trying to help Jacobo find an attorney.

“Absolutely not,” Kim said, adding that she brought Jacobo to the Rose Pak gala because she had flown to New York to grieve her father’s death and wasn’t paying close attention to the news of him being accused of rape.

“I had asked Jon and [TODCO President] John Elberling and other folks to join my table [at the gala] prior to leaving,” Kim said. “And when I came back, it just wasn’t something that I was tracking.”

Five days after the gala, Kim issued a statement saying it was a “mistake” to bring Jacobo to the event, and he “should be 100% accountable for his actions.” She added that she had spoken with Perigo and officials with the SF Women’s Political Committee.

Nadia Rahman, who was president of the SF Women’s Political Committee at that time, told The Standard that Kim had not spoken to anyone on the board of the organization.

“Jane’s tweet was not the truth, sadly,” Rahman said. “At that point, no one on our board had received outreach from her, and we wanted to make it clear that no one can lie about engaging with our organization.”

An actual conversation took place shortly after the Twitter spat, and Kim told the Standard that the Women’s Political Committee informed her of other allegations against Jacobo, but “nothing came of it.”

After that, Kim said, “I had just assumed that there weren’t any more allegations.”

In a text message a day after speaking with The Standard, Kim wrote that the subsequent accusations from the three women against Jacobo “are indeed concerning, constituting serious crimes that demand thorough investigation by the San Francisco Police Department.”

Rahman said she believes that part of the reason it took years for these women to come forward publicly is because of San Francisco’s “political machine” and Jacobo’s ties to powerful figures like Kim and TODCO’s Elberling, who was profiled in a Chronicle story with the ominous headline: “You don’t mess with him.”

Elberling told The Standard in 2022 that he was planning to retire soon and wanted Jacobo to take over the organization’s financial structure, which would give Jacobo control of hundreds of thousands of dollars in spending on local polling and ballot measures. Elberling did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

“I’m not surprised that [Jacobo] has avoided accountability, because of the political spaces that he moves in,” Rahman said. “This is the culture. … It’s very crony that people stay within their lanes unless you’re directly attacking somebody in the other tribe.”

Anna Yee, TODCO’s CEO, said in a statement that after Perigo accused Jacobo, the organization conducted an internal review of his work with staff and the community and found no wrongdoing. “The investigation of accusations such as these is outside the scope of a social justice, service nonprofit,” Yee said. “These are matters for the proper authorities.”

Jacobo continues to work as TODCO’s director of community development.

‘I believed it without a shadow of a doubt’

After a night out of drinks and dancing in December 2016, longtime Oakland Recreation and Park Commissioner Evelyn Torres invited three friends back to her home for a nightcap. The group included Jacobo, his friend Jonathan Garcia and a woman who worked with Jacobo in San Francisco politics.

When the group got back to Torres’ home, the woman fell asleep in the living room, Torres said. Torres recalled going to her kitchen with Garcia to pour a glass of wine. But when they came back, Jacobo and the woman had disappeared.

Torres looked for her friend in the bathroom. Then, she checked her own bedroom. She ripped a blanket off the bed and said she found Jacobo undressed down to his boxers. Next to him was her friend—topless and unconscious.

Torres started screaming at Jacobo to get out, jolting the woman’s senses.

“I thought it was a dream,” the woman said. “I remember her yelling: ‘Get the fuck out of my house!’”

Jacobo left the home with Garcia, who did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

“Jon was definitely functional and could definitely understand everything I said,” Torres told The Standard. “I think he would have definitely taken advantage of her.”

The woman said she did not recall how she got into the bedroom, or how her top was removed. In the morning, the woman looked at her phone and found a “ridiculous” number of missed calls from Jacobo.

“Over a dozen text messages from Jon saying, ‘Hey give me a call, call me, please talk to me, call me before you talk to anybody. I really need to talk to you,’” she said. “He didn’t say anything else other than I needed to talk to him.”

Days later, she agreed to meet Jacobo in a public space near San Francisco City Hall. He told her he had no memory of the night, she said. Then he began to cry, she said, expressing his love and admiration for her, as well as talking about how important his sister and deceased mother were to him. When she challenged him, she said, he became angry.

She felt he was trying to manipulate her and recalled telling him, “This is predatory behavior. You’re not a good man nor a good person.”

Lito Sandoval, an LGBTQ+ and Latinx activist in San Francisco, confirmed to The Standard that the woman told him about the incident at Torres’ home in December 2016, just days after it happened. Sandoval recalled her telling him she no longer felt comfortable working in close proximity to Jacobo on local political efforts.

“He’s very charming. He’s a people person,” Sandoval told The Standard. “But he’s got a dark side.”

What Torres and Sandoval didn’t know was that this wasn’t even the woman’s first frightening encounter with Jacobo.

About six months earlier, after a night out with political friends in the summer of 2016, she said, Jacobo attempted to drive home after having drinks. Instead, the group dissuaded him. The woman, who was not intoxicated, agreed to let Jacobo sleep on a couch in the living room of an apartment she shared with roommates. She had a boyfriend and made it clear to Jacobo she wanted to be nothing more than friends, but the next morning, the woman awoke in her own bed and felt an arm around her.

“In my mostly asleep brain, I thought that was my boyfriend,” she said. “And so I grabbed his hand and kind of held it a little closer until I kind of realized—somehow it just clicked, like, ‘Wait a minute. What the fuck?’ He just smelled differently. And that’s when I realized that it was Jon.”

Jacobo not only snuck into her bed, she said, but he was also naked.

“He got on top of me and was trying to convince me, saying, ‘I’ve always loved you. You know, we can be so great together. You’re so fucking amazing. You’re so hot,’” she recalled. “He just started saying all this stupid shit and holding my arms above my head tightly down.”

As he tried to kiss her and undress her, she said, she felt shock and fear but told him, “Choose your next actions very carefully. Think about what you’re going to do next, because ‘no means no.’” She had to say it twice to get through to him.

Like snapping out of a trance, she said, Jacobo quickly grabbed his clothes and left. After that, she avoided him when possible, but it was difficult because of the common friends and political associates they shared.

After seeing Perigo’s story in 2021 and learning there were other women with serious allegations against Jacobo, she decided to go to the police.

“When I read Sasha’s story, I believed it without a shadow of a doubt,” she said, “because so much seemed so familiar.”

Torres, who also worked as a staffer for Rep. Barbara Lee, said she felt it was important to speak out now on behalf of her friend after learning of Jacobo’s alleged pattern of predatory behavior.

“I think he’s very aware that people will feel shame, people will feel like they won’t be heard or it might affect their career, so they won’t come forth,” Torres said. “I think he’s continued to do it to so many women, because he’s seen the pattern that they’re not coming forth. And if they are [coming forward], people are not listening.”

‘I am still haunted’

More than three years have passed since Perigo came forward and told her story, and she feels there has been an utter lack of accountability.

“There is absolutely no reason to believe he has changed,” Perigo said. “He has lied about this multiple times. He continues to be dangerous.”

On social media, Jacobo frequently talks about overcoming adversity while taking aim at anonymous opponents, such as a tweet thread he wrote last spring after the San Francisco Chronicle published a story that notably did not mention him as a potential candidate for Mission District supervisor.

“And to all them people talking about my life, what they think I did, didn’t do, will do, won’t do, STFU,” Jacobo wrote. “Tend to your own garden it’s looking real dry and dead on that side. I hate to see that for you.”

And to all them people talking about my life, what they think I did, didn’t do, will do, won’t do, STFU.

— Jon Jacobo (@Jon_Jacobo) April 19, 2023

Tend to your own garden it’s looking real dry and dead on that side. I hate to see that for you.

Whew, okay now I’m done. 😆

The woman who dated Jacobo for years and accused him of abusing her and threatening to kill her said it’s been “devastating” that nothing has happened since she and the other women went to police.

“I am still haunted by the fact that Jon is out there and is in a position of power and may be harming other women,” she said.

In addition to his role at TODCO, Jacobo is now a spokesperson for the Mission Street Vendors Association, which has been in active negotiations with the city over the street vending ban imposed in the area last year. Bay Area Community Resources—an organization that has received hundreds of thousands of dollars in state funding—welcomed Jacobo just last month as a keynote speaker for an event honoring young immigrant entrepreneurs.

Ruth Ferguson, a San Francisco resident who co-founded the organization Stop Sexual Harassment in Politics, called the actions of Perigo and the three women coming forward “courageous.” But, she added, it is disturbing to hear Jacobo’s inner circle may have insulated him from accountability.

“We deserve to have a local government and a local political community that is functioning properly and supporting our values and interests,” Ferguson said. “I don’t think anybody who’s had serious accusations of sexual violence should be in a position of power.”

More recently, Jacobo’s social media posts have indicated he is now sober and engaged to Gabriela López, who served as president of the San Francisco Unified School District board before voters recalled her in 2022.

In an Instagram post on New Year’s Day documenting the couple’s engagement—Jacobo proposed in front of the Manhattan Bridge—he said that the couple has been through many ups and downs but “never lost touch and never grew apart.” The couple also announced they are expecting a child.

The three women coming forward now say they hope law enforcement will take a fresh look at the totality of their cases.

Randy Quezada, a spokesperson for the District Attorney’s Office, said in a statement that local prosecutors will use “every tool” available for sexual assault cases, including propensity evidence, which allows proof of a person’s character to be used as evidence.

Perigo said she was unaware of all of the experiences of the three other women before she came forward in 2021. She is now reconsidering whether to go to police with her own accusations.

“Knowing what I know now about the depth of Jon’s alleged crimes and that my story is just the tip of the iceberg, my position on the usefulness of criminal prosecution has shifted a little bit,” Perigo said. “I think there are legitimate public safety issues to consider.”