Scandal.

Politicians are known for it. Voters expect it. But like plaque building up against a molar, enough of it can give a campaign a stinging cavity.

There are already signs that the sheer volume of accusations splaying across phone advertisements and blaring on TVs may have taken a toll on two candidates running for San Francisco mayor: former Supervisor and interim Mayor Mark Farrell and Mayor London Breed.

As voters mail in their ballots, confusion is understandable. The sheer number of allegations is a dizzying mess.

For those of you having trouble keeping track of these malicious accusations, The Standard has compiled most of the major alleged (and sustained) misdeeds against the top candidates into what we’re calling our mayoral dossier.

Use the anchor links below to navigate. That’s right — there are so many scandals that we needed to write a table of contents. 😬

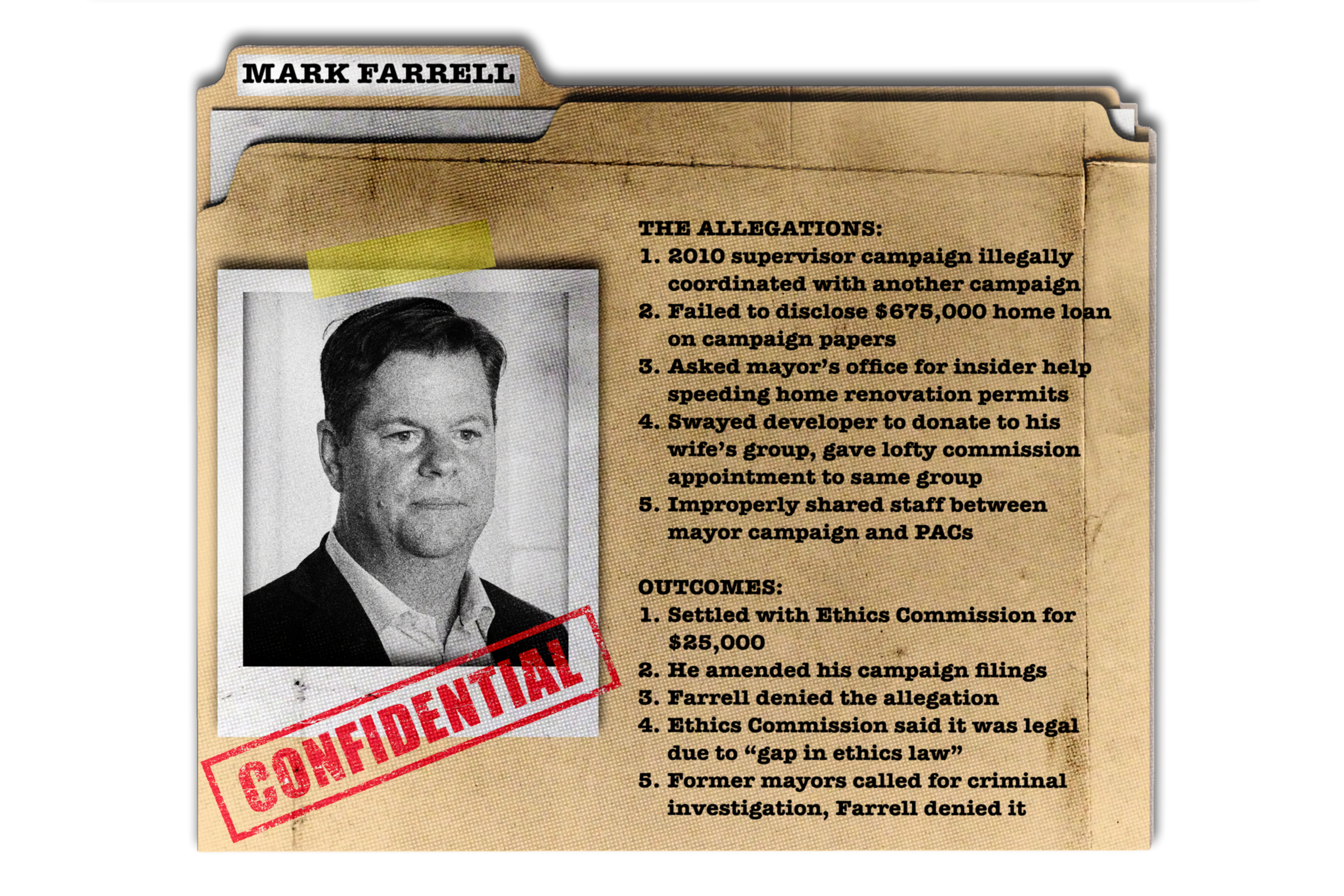

Mark Farrell

- The $191,000 fine that wasn’t

- How hard is it to buy a house?

- Friendly Farrell favors

- Mayoral campaign’s questionable connections

London Breed

- Shrimp Boy’s salacious revelations

- Breed’s brother

- The Nuru scandal’s web of corruption

- Dreams, dreams, dreams

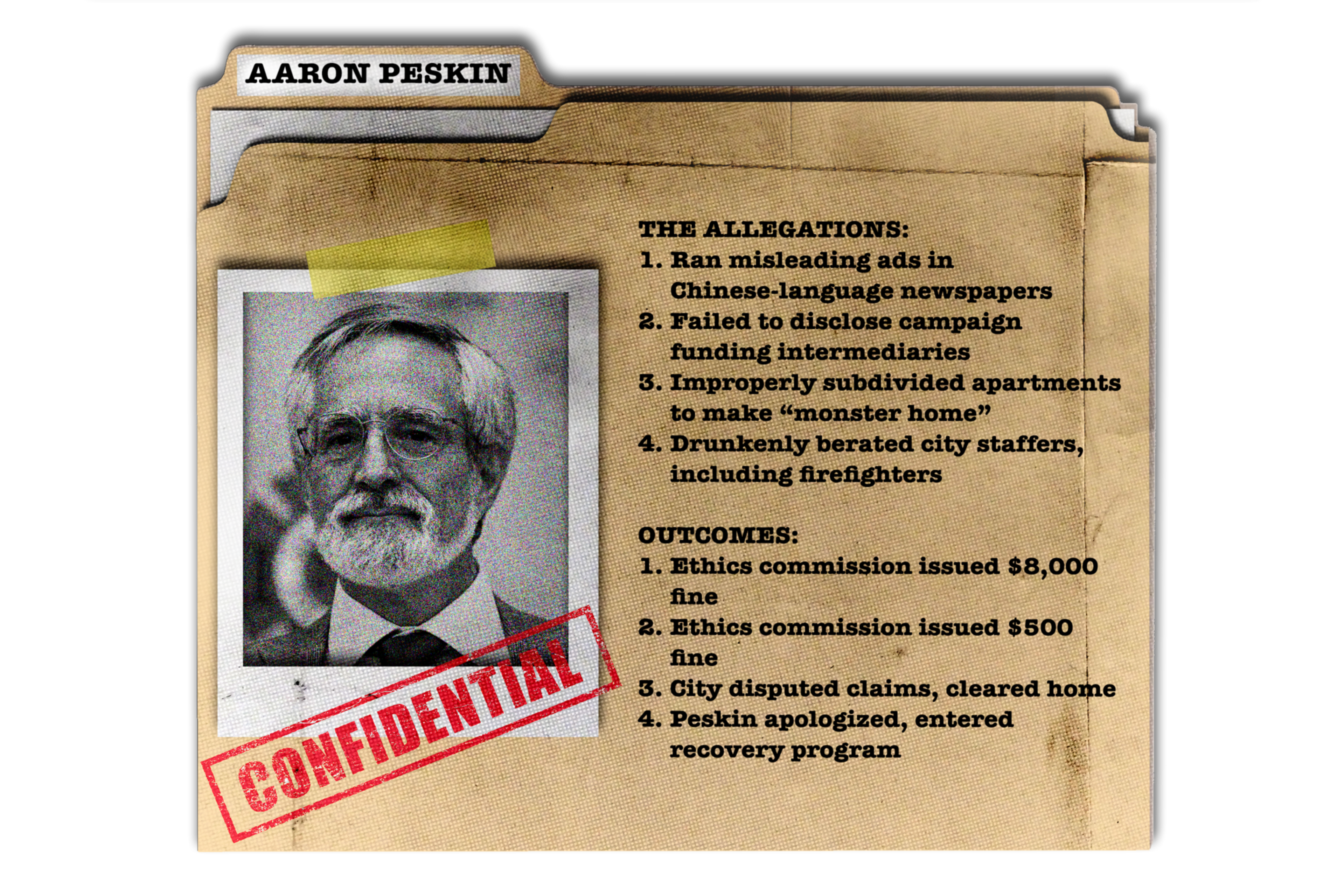

Aaron Peskin

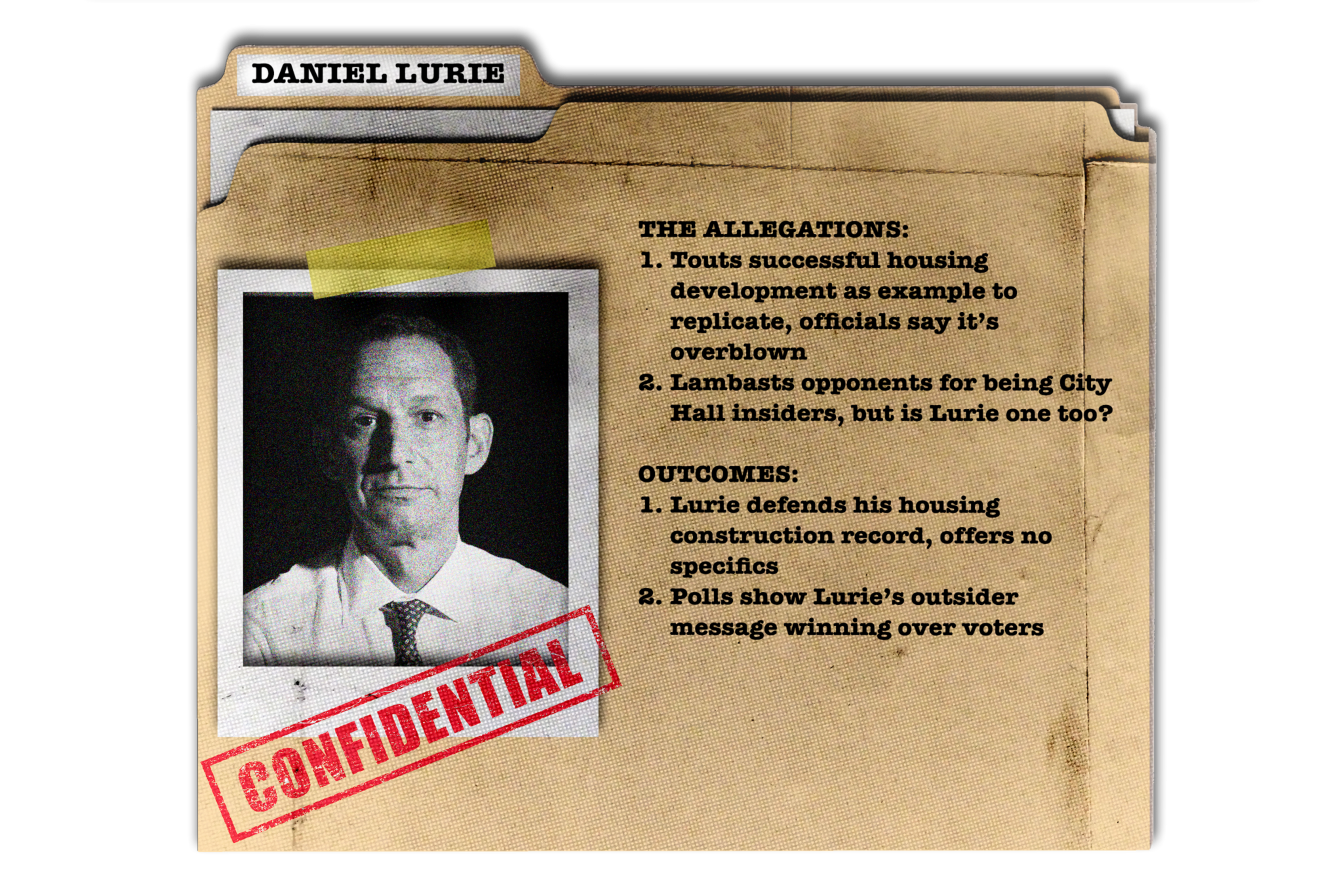

Daniel Lurie

Mark Farrell

The $191,000 fine that wasn’t

The allegations: In 2010, Farrell won a squeaker of a Board of Supervisors race, beating top opponent Janet Reilly by a scant 258 votes. Reilly snapped back, filing a complaint with the Fair Political Practices Commission alleging Farrell and his campaign consultant illegally coordinated with a PAC (opens in new tab) to beat her. PACs can raise money in unlimited amounts, while candidate campaigns can only raise money in $500 increments. Federal law bans PACs and candidate campaigns from coordinating, but political insiders know it’s a tough accusation to prove.

The outcome: The city’s Ethics Commission initially hit Farrell with the largest fine in its history: $191,000. Farrell called the fine a “witch hunt” and sued to clear it (opens in new tab), eventually paying just $25,000 in a settlement with the city.

How hard is it to buy a house?

The allegations: Farrell was accused of dodgy dealings around the nearly $5 million Jordan Park home he purchased in 2020. Earlier this year, Breed told The Standard that Farrell had approached one of her staffers to ask for help expediting permits to remodel the home, a claim he denied. Breed said the phone call took place in 2019, when Farrell was allegedly arranging an off-market purchase of the home. In October, the San Francisco Chronicle revealed Farrell failed to disclose a $675,000 private loan (opens in new tab) given by the home’s previous owner, Paul Danielsen, on his campaign paperwork. Ethics laws say officials should disclose such loans so the public knows who they owe money to.

The outcome: Farrell filed the necessary campaign paperwork regarding the home loan after it was revealed. As for the phone call, Breed didn’t recall when exactly it took place, and Farrell disputed the mayor’s recollection of the call.

Friendly Farrell favors

The allegations: In 2015, Farrell reached out to developers building housing in the neighborhoods he represented to donate $17,500 to the San Francisco Parks Alliance, a nonprofit organization his wife, Liz Farrell, chairs, to help open schoolyards for kids on weekends, according to a Chronicle report (opens in new tab). One of those developers, the Prado Group, also made a $2,500 donation (opens in new tab) to Farrell’s campaign for the Democratic Party. Farrell tried passing legislation to benefit them, leading to accusations of a pay-to-play transaction. The Standard also revealed Farrell accepted a $5,000 contribution from a PAC formed by Recology, the city’s trash company, and just over a week later nominated Recology exec Paul Giusti to the Treasure Island Development Authority. Giusti later admitted to arranging more than $1 million in bribes to other city officials.

The outcome: There was no evidence the Parks Alliance fundraising — legally known as a behest payment — and Farrell’s legislation to benefit the developers were related. The Ethics Commission said it may have been permissible, though they said it was because of a “gap in ethics laws,” suggesting they wanted to close the loophole. Farrell returned the $2,500 donation to the Prado Group after the Examiner exposed it. At the time of The Standard’s reporting, Recology said it instituted new compliance practices to end the questionable contributions.

Mayoral campaign’s questionable connections

The allegations: You’d need one of those yarn-connected conspiracy corkboards to map out this one. Investigations by the Chronicle and The Standard show Jay Cheng, the power broker behind the big-money PAC Neighbors for a Better San Francisco, tried to hire staffers for Farrell’s campaign for a cushy $15,000 monthly salary. The problem? Candidates and PACs aren’t supposed to coordinate, raising questions about ties between the Farrell camp and Neighbors. Similarly, Mission Local (opens in new tab) revealed a former Farrell staffer, Margaux Kelly, had said she, Jay Cheng, and TogetherSF CEO Kanishka Cheng were “guiding the ship” for Farrell’s campaign. The Standard and the Chronicle (opens in new tab) have also detailed instances where Farrell’s campaign used resources from his Proposition D campaign, which has looser donation limits — again suggesting he’s bending the rules on campaign finance.

The outcome: Farrell denied anyone from Neighbors or TogetherSF was working for his campaign. Dissatisfied, former mayors Willie Brown, Frank Jordan, and Art Agnos penned a joint letter with other city officials asking Attorney General Rob Bonta and District Attorney Brooke Jenkins to conduct a criminal investigation into Farrell’s campaign. No word yet if they are.

London Breed

Shrimp Boy’s salacious revelations

The allegation: The 2015 prosecution of Chinatown gang leader Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow became a mother lode of corruption allegations after a sealed court document rife with FBI evidence leaked to the public. Many San Francisco officials were implicated in its thrilling, crime-novel-like pages, including then-Supervisor London Breed. One character in this saga was politically connected businessman Derf Butler, who had contracts with the city’s transit agency and would eventually plead guilty (opens in new tab) to bid rigging in Alameda County. In the Shrimp Boy court filing, Butler told a source (opens in new tab) working with the FBI that he “pays Supervisor Breed with untraceable debit cards for clothing and trips in exchange for advantages on contracts in San Francisco.”

The outcome: Not much came of the allegation. Chow was found guilty and is serving time in federal prison to this day. Breed told NBC Bay Area (opens in new tab) at the time that “the attorneys for a man who’s facing multiple felony charges tried to get him off the hook by making baseless allegations against many other people, including a number of local African-American leaders.”

Breed’s brother

The allegations: Breed’s brother, Napoleon Brown, served time in Solano State Prison for manslaughter and robbery, among other crimes, after he robbed a Johnny Rocket’s on Chestnut Street in 2000 and his girlfriend died in a car crash during their pursuit. In 2018, Breed wrote to then-Gov. Jerry Brown (opens in new tab) asking for leniency on his sentence. But she wrote it while referring to herself as “mayor,” which drew widespread concern that she was seeking to use her position to influence the sentencing.

The outcome: Breed’s brother was granted a reduced sentence by a San Francisco County Superior Court judge last year. When the Ethics Commission fined Breed over an unrelated scandal that we’ll get into next, it referenced the letter (opens in new tab) to the governor, calling it “a misuse of her City title.”

The Nuru scandal’s web of corruption

The allegation: Bust out another corkboard and re-spool your yarn. In 2020, the Department of Justice charged then-public works director Mohammed Nuru in a wide-reaching bribery scandal. Shortly after the allegations were revealed, Breed admitted she had a romantic relationship with Nuru (opens in new tab) some decades ago (though the timing has been publicly disputed). She also revealed that Nuru paid $5,600 to repair her car, which she failed to disclose to the Ethics Commission. But wait — there’s more! An investigation by yours truly also revealed she failed to disclose a $1,250 pride float (opens in new tab) paid for by Nick Bovis — one of the many actors accused of bribing Nuru.

The outcome: While Breed herself was never accused of anything, the corruption scandal took down several of her confidants. Nuru and former Public Utilities Commission general manager Harlan Kelly were both found guilty and are in prison. The COVID pandemic started shortly after the accusations against Nuru were announced, taking the public’s attention away from the scandals. In 2021, the Ethics Commission fined Breed $22,792 for the pride float and car repair incidents (opens in new tab), which one of her campaign donors later paid on her behalf

Dreams, dreams, dreams

The allegations: Breed’s 2024 mayoral campaign suffered a system shock when both The Standard and the Chronicle revealed allegations against Human Rights Commission head Sheryl Davis. Through the Dream Keeper Initiative, the mayor’s signature program to help the Black community, Davis allegedly awarded $1.5 million in contracts to a man she shared a home with and mishandled fund disbursements (opens in new tab). While Breed wasn’t implicated, Davis is her longtime friend, and the program was one she conceived of and championed.

The outcome: Davis resigned. Breed said she was “appalled” by the findings. Numerous organizations helping the Black community, that were funded by Dream Keeper, saw their future grants frozen. We’re not soothsayers, but after the election, we may have a clearer picture of just how badly the Dream Keeper scandal hurt Breed’s reelection campaign.

Aaron Peskin

What’s in an election ad?

The allegations: For a guy who’s run for supervisor 5 times, it’s surprising to see that Peskin didn’t have his campaign records down to a science. His 2015 campaign had “pervasive” problems in ads he took out in Chinese-language newspapers, the Ethics Commission alleged (opens in new tab). The commission also said his ads were misleading enough to lead some readers to believe the Sing Tao Daily and World Journal had endorsed him. A separate Ethics Commission audit of his campaign found Peskin failed to disclose some intermediaries who helped get people to donate to his campaign.

The outcome: Peskin netted fines for both: $8,000 for the Chinese-language newspaper snafus and a proposed $500 for the shaky audit.

Home divisions sow divisions

The allegations: In 2019, YIMBY supporter Vincent Woo penned a Medium post accusing Peskin — long viewed by YIMBYs as the chief of the NIMBY movement — of illegally subdividing his Filbert Street home. What should’ve been a duplex, Woo argued (opens in new tab), was instead a “monster home” that Peskin broke city rules to create. Woo had receipts aplenty: permits, communications, and more. And to add a little of that hypocritical grist to the grill, it came at a time when Peskin was legislating against people’s ability to create their own monster homes.

The outcome: The Department of Building Inspection cleared Peskin (opens in new tab). DBI itself isn’t necessarily the most reliable of city agencies. Its inspectors were caught up in the Nuru scandal with at least one being found guilty in a bribery scheme.

Drinking and firefighting

The allegations: Perhaps the most pernicious knock on Peskin is the long-standing accusations that he drunkenly called and berated city staffers for years. The reports arose during then-Mayor Gavin Newsom’s administration (opens in new tab), when Peskin allegedly threatened to eliminate jobs and cut agency funding to the Port of San Francisco after its staffers disagreed with him on building height limits along the waterfront. “The threats appear to be extensive and real, and I fully expect to have difficulty with any Port legislation pending before the Board of Supervisors,” read a letter from the port’s executive director. The reports were an issue in Peskin’s 2015 campaign, when billionaire Ron Conway paid for Mad Men-style TV ads (opens in new tab) calling attention to his behavior. The situation reached its apex when Peskin drunkenly berated city firefighters (opens in new tab) as they actively poured water on a burning North Beach building on Union Street. “He was yelling in the general direction of the [command post], waving his arms around and pointing his fingers at our members,” operations fire chief Mark Gonzalez wrote in a report.

The outcome: Peskin won his 2015 election despite the attack ads from Conway. In 2021, Peskin issued an apology for his alcoholism and bullying (opens in new tab). His recovery has become a cornerstone of his mayoral campaign.

Daniel Lurie

Lurie’s shaky housing miracle

The allegations: Lurie has never worked in government, having used his family wealth to launch a nonprofit called Tipping Point Community. So when it comes to political scandal, there isn’t much. But his opponents have seized upon his thin record, accusing him of inflating his resume. Take 833 Bryant St.— one of Lurie’s main talking points. To build it, Lurie’s Tipping Point Community secured tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic donations and used modular construction from a factory in Vallejo that labor unions in San Francisco oppose. San Francisco Building and Construction Trades Council President Larry Mazzola Jr. told The Standard the project was also riddled with construction errors, including plumbing problems.

The outcome: Lurie didn’t provide specifics to The Standard about overcoming political hurdles to embrace modular housing. He did say he would “overhaul corrupt bureaucracy,” adding, “I have delivered once, and I will deliver again.”

Is he actually an outsider? Signs point to no

The allegations: On the campaign trail for mayor this election, Lurie has repeatedly dinged his opponents for being “City Hall insiders.” Indeed, his attack ads have heavily leaned into the scandals on this very list. But it’s hard to argue that Lurie, a Levi Strauss heir with a rolodex of powerful friends, is truly an outsider. In 2015, Lurie was well-connected enough at City Hall to be tapped to chair the Super Bowl 50 Host Committee, which leveraged his connections (opens in new tab) to realize then-Mayor Ed Lee’s dream of a Super Bowl City. He’s also got insiders like Jason Elliot and Steve Kawa — former advisers to Newsom and Lee — on speed dial. To cap all this off, Lurie’s wife Becca Prowda works for Newsom, who also played bongos at Lurie’s 2006 wedding (opens in new tab). If you’re that chummy with Newsom, would it be fair to characterize you as disconnected from politics?

The outcome: Lurie has publicly admitted connections to City Hall but makes the distinction that he is not part of it. Lurie is leading recent polls, largely on the strength of his claims that he’s an outsider who will shake up the political system. That message may just land him in the mayor’s office.